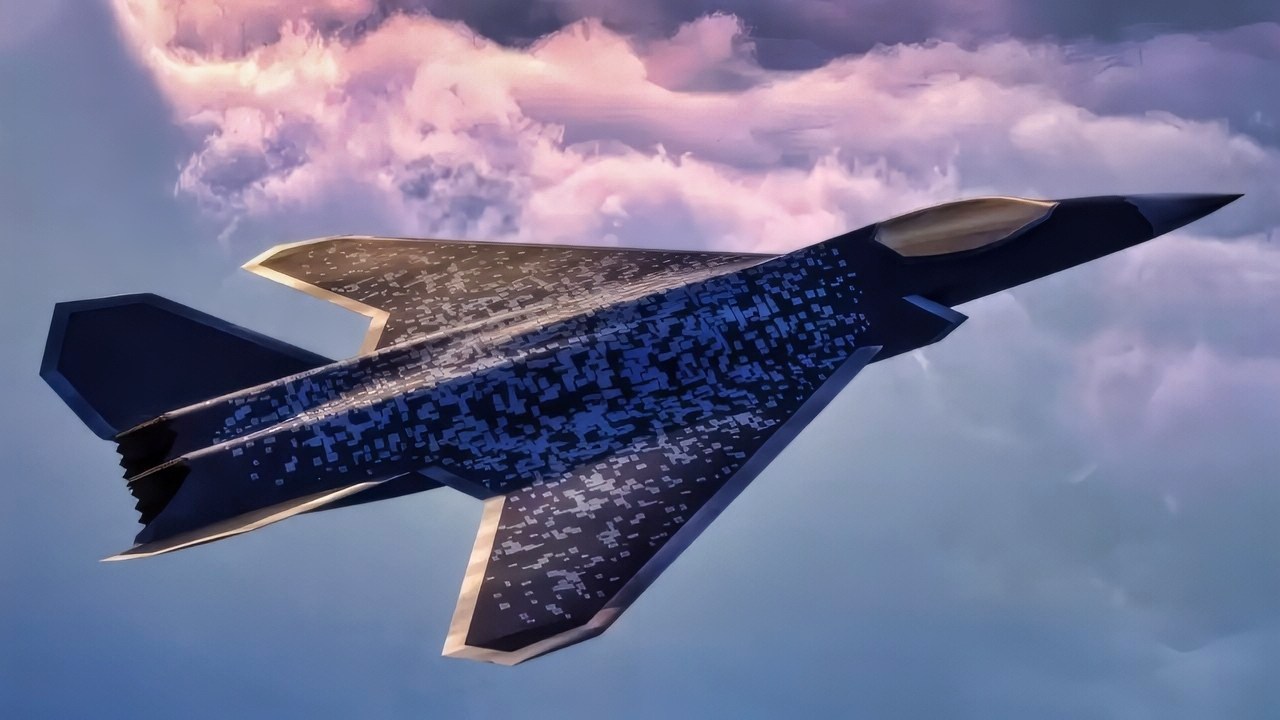

Will the Franco-Spanish-German Future Combat Air System (FCAS) fighter project move off the drawing board and into the air? It seems increasingly unlikely.

KEY POINTS – Europe’s Future Combat Air System, led by France, Germany, and Spain, is drifting as industrial and strategic rivalries harden.

Dassault CEO Eric Trappier doubts partners can align, criticizing Germany’s continued dependence on U.S. equipment and resisting Airbus demands for a bigger role.

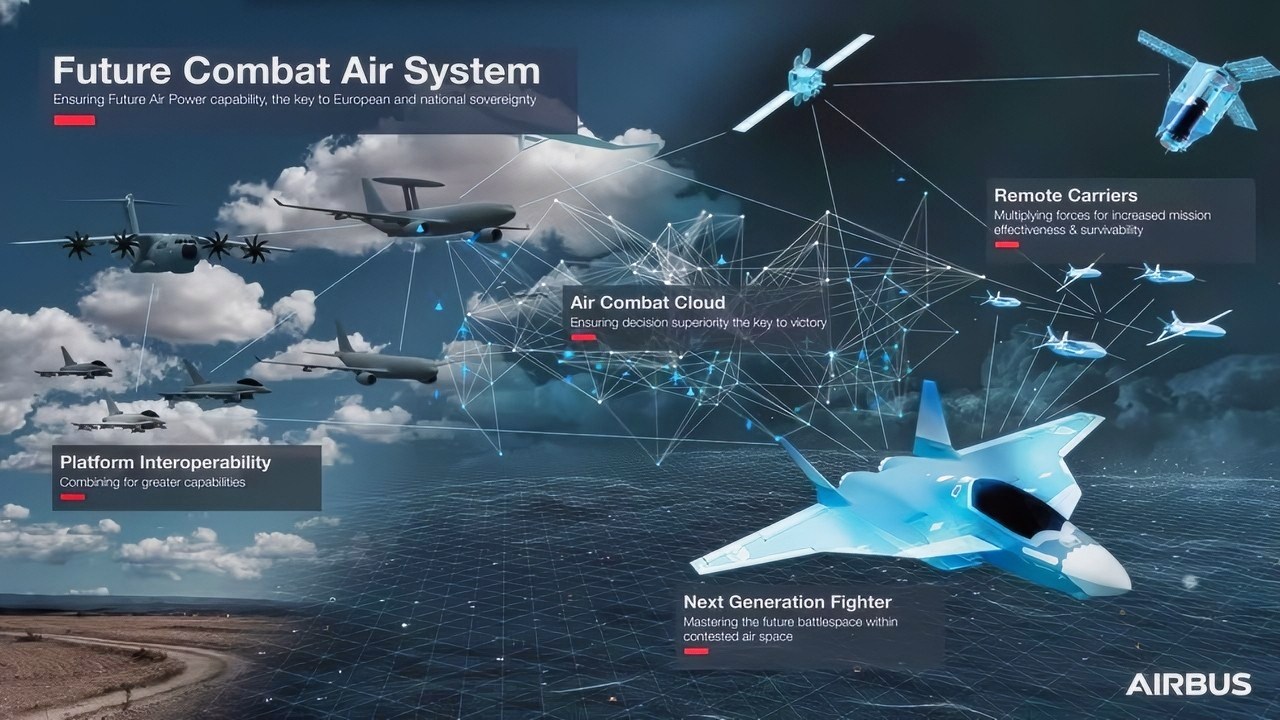

FCAS Graphic. AIRBUS Handout.

FCAS centers on a Next-Generation Fighter to replace Rafale and Eurofighter fleets, but disagreements over leadership, mission priorities, and nuclear integration keep the jet on paper.

Some officials now argue a shared “combat cloud” data-and-command network matters more than a single aircraft—and could arrive sooner, before costs and timelines spiral further.

Europe’s FCAS Has a Message: Sixth-Gen Unity Isn’t Guaranteed

Dassault Aviation CEO Eric Trappier expressed strong skepticism that the companies involved in the advanced fighter project will be able to set aside their differences. He took particular issue with Germany’s continued reliance on U.S. kit to meet its defense needs. “Will it happen? I don’t know,” Trappier said during a security conference.

The Future Combat Air System would be a sixth-generation fighter jet that would serve in the air forces of the three partner nations. The initiative aligns with Europe’s growing desire to diversify away from U.S. weapon systems—a position spurred by U.S. President Donald Trump’s mercurial attitude toward a continent he sees as free-riding on American security guarantees.

At the heart of the Future Combat Air System is the Next-Generation Fighter, which would replace several fighter jets currently in service: France’s Rafales, built by Dassault, as well as Spain and Germany’s Eurofighter Typhoons.

The growing fracas between Paris and its project partners, Madrid and Berlin, previously made headlines when Politico pulled back the veil on frictions within the relationship.

“According to two people familiar with the discussions, the German defense ministry raised FCAS in talks last week with Airbus, which is responsible for Germany’s part of the jet’s development and construction,” Politico explained. “The conversations laid bare Berlin’s discontent with what officials see as a push by French industry for an outsized role in the program. That attitude has pushed the Germans to weigh fallback options, including moving ahead without France. The company was told that the German government is exploring potential closer cooperation with Sweden or the U.K. — or going it alone with Spain.”

Eurofighter Typhoon Fighter Training. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

A Eurofighter Typhoon with the Spanish Air Force based out of Morón Air Base, Spain, refuels from a KC-130J Hercules, a first for the Marines from Special-Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Force Crisis Response-Africa, Aug. 13, in Spain. The U.S. and Spain have been fostering one of the closest defense partnerships around the world for more than 60 years. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Staff Sgt. Vitaliy Rusavskiy/Released)

At some point [the German] parliament will have to say: ‘Either we need this aircraft or we don’t,’” Andreas Schwarz, a lawmaker with Germany’s center-left Social Democrats, told Politico. Mr. Schwarz warned that the production of that aircraft has not yet begun, and that “many unforeseen problems” are likely to arise should the project proceed as it currently stands.”

France and Germany have previously attempted to reconcile their differences and find a compromise that would allow FCAS to move forward—but agreement has proved to be elusive. At its core, the FCAS disagreement stems from differing operational roles that each of the partners sees fighter carrying out within their respective air forces.

Previous reporting hinted at a shift in priorities toward developing a combat command-and-control system dubbed “combat cloud.” This would connect pilots in the air with a range of ground-based sensors as well as nodes in space and at sea. And while the future of FCAS seems to be in limbo for now, the combat cloud continues to move forward.

Three European officials acquainted with the FCAS project outlined, in broad strokes, where the FCAS project could move in light of its new goal. One of the three officials said, “We [the Europeans] can live with several jets in Europe but we need one cloud system for all of them.” A second official explained that “all the other elements [of FCAS] are working well. Why would we stop doing that? There is no need for FCAS to founder completely — there is a need for a combat cloud system.”

The last of the trio said a decade could be shaved off the project’s timeline, making it ready by 2030 instead of 2040.

France’s Dassault has insisted that it should take the lead on the Future Combat Air System. That insistence is partly due to France’s position as one of Europe’s few nuclear-armed powers. France has a long tradition of maintaining its strategic autonomy, particularly in combat aviation and nuclear weapons.

Germany, on the other hand, has a more modest aviation ecosystem, and though Berlin’s Panavia Tornado jets are certified for nuclear weapons operations under the auspices of NATO’s nuclear-sharing umbrella, Germany does not build nuclear weapons itself. Instead, the Luftwaffe has access to American tactical nuclear weapons.

Integration between a new sixth-generation fighter jet and France’s own nuclear weapons would be an understandable goal for Dassault, but a compromise could be tough to find. In any event, Germany and Spain may already be looking for other partners to join FCAS in anticipation of a French withdrawal.

Sweden and the United Kingdom are rumored to be potential candidates, given their aerospace expertise. But whether FCAS can be saved at all remains to be seen.

About the Author: Caleb Larson

Caleb Larson is an American multiformat journalist based in Berlin, Germany. His work covers the intersection of conflict and society, focusing on American foreign policy and European security. He has reported from Germany, Russia, and the United States. Most recently, he covered the war in Ukraine, reporting extensively on the war’s shifting battle lines from Donbas and writing on the war’s civilian and humanitarian toll. Previously, he worked as a Defense Reporter for POLITICO Europe. You can follow his latest work on X.