Article Summary: The Seawolf-Class Was a Masterpiece. Washington Treated It Like a Luxury

-The Seawolf-class was supposed to be the U.S. Navy’s apex hunter-killer submarine: fast, deep-diving, and almost impossibly quiet.

USS Connecticut (SSN 22) is docked for its Extended Docking Selected Restricted Availability July 12, 2023 at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard; Intermediate Maintenance Facility.

-The Navy planned to buy 29. It built three. The Cold War ended, the “peace dividend” arrived, and Seawolf was deemed too expensive for an era that thought serious naval war was over.

-That choice reshaped the fleet from the 1990s to today, forcing a retreat to the smaller Virginia-class while Los Angeles-class boats now retire faster than Virginias can be built.

-As a submarine shortfall looms in the 2020s and 2030s, the Seawolf program’s one great flaw is painfully clear: numbers.

The Great Seawolf-Class Submarine Never Met Its Full Potential

If you set out in the 1980s to design the ultimate American attack submarine, you would end up very close to the Seawolf-class.

Bigger than a Los Angeles-class boat, faster, deeper-diving, and far quieter, the Seawolf was built to hunt Soviet submarines in the deep oceans, slip under Arctic ice, and carry a staggering loadout of torpedoes and cruise missiles. It was the undersea equivalent of a heavyweight prizefighter: overbuilt, overpowered, and unapologetically expensive.

The original plan reflected that ambition. The U.S. Navy wanted a fleet of roughly 29 Seawolf-class boats to replace Los Angeles-class submarines and guarantee dominance in any high-end undersea fight.

Then the Soviet Union collapsed.

By the mid-1990s, Washington’s mood had flipped from existential fear to “peace dividend” optimism.

The same Congress and Pentagon that once worried about third world war scenarios in the North Atlantic and Arctic now saw Seawolf as a relic of a fight that never came — a gold-plated solution to a problem they believed had disappeared.

The result is the single biggest flaw in the Seawolf story: not the design, not the technology, but the decision to stop at three boats.

As one former U.S. Navy officer told me a few months back: “I have to call the Seawolf-class submarine shortage extremely dangerous as we have a capability gap we just can’t close.”

What Seawolf Brought to the Table

To understand what was lost, you have to appreciate what Seawolf actually is.

These boats were designed from the keel up to outclass anything the Soviet Union could put to sea. They use stronger high-yield steel than earlier U.S. subs, allowing greater diving depth. They are widely understood to be among the quietest and fastest nuclear-powered attack submarines on earth, with the ability to sprint and still remain very hard to detect.

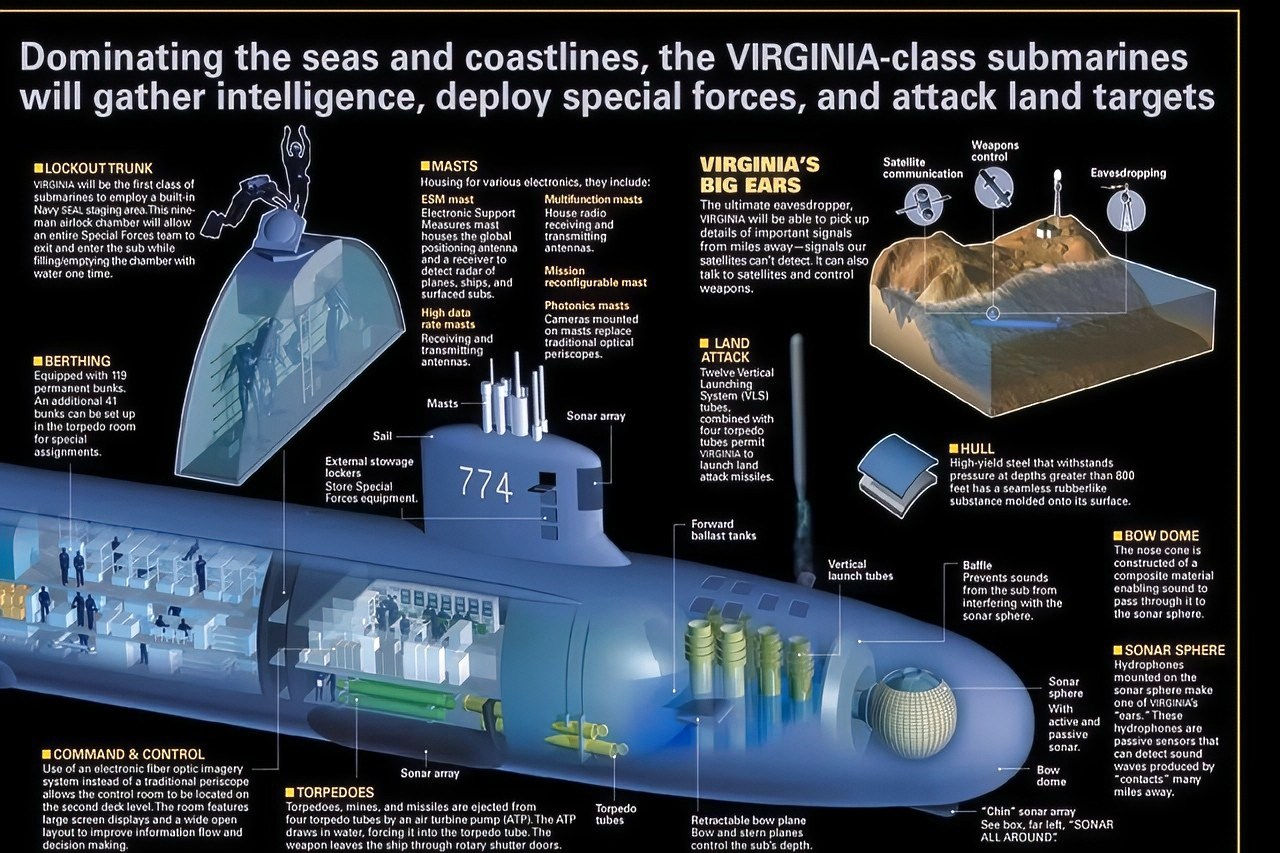

Armament is equally ruthless. Instead of the usual four torpedo tubes, Seawolf carries eight large-diameter tubes and can pack around 50 weapons in its torpedo room — a mix of heavyweight torpedoes and Tomahawk cruise missiles. That means a single Seawolf can sit in a patrol box for a long time, stalking enemy submarines, surface ships, or land targets without having to reload.

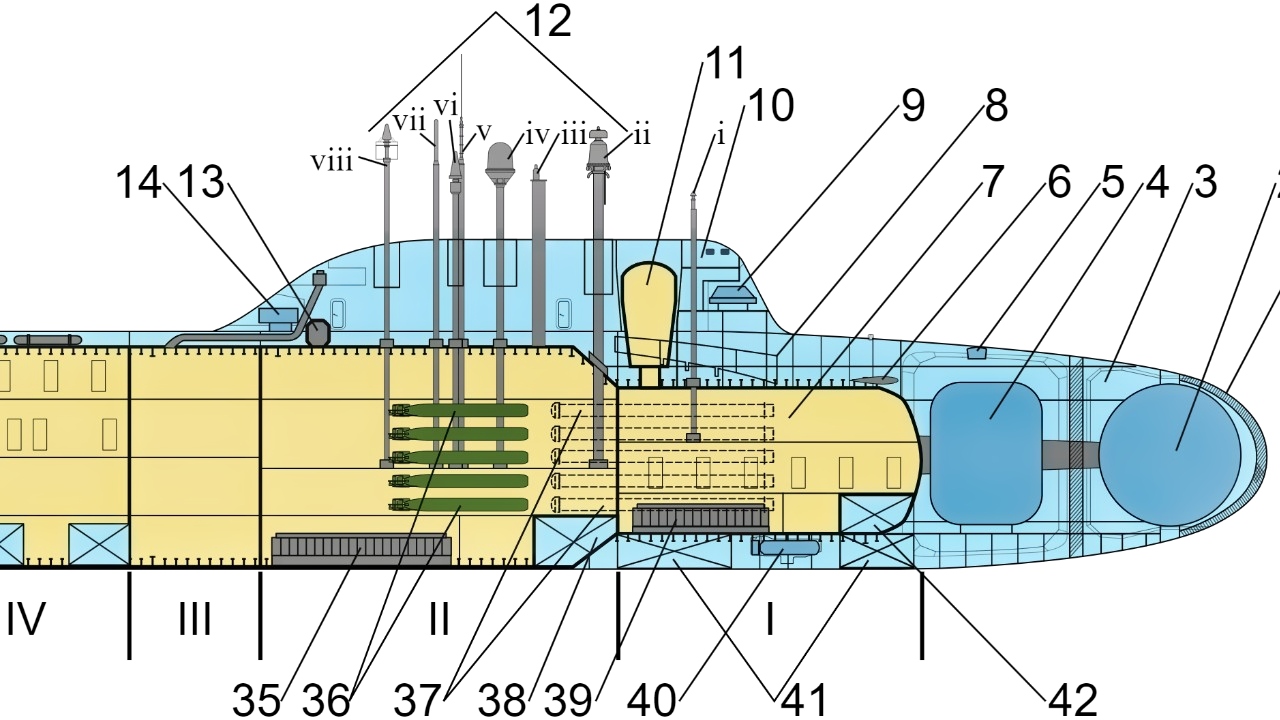

On the sensor side, Seawolf introduced advanced sonars and combat systems that dramatically improved detection ranges and tracking fidelity. A large spherical bow array, wide-aperture flank arrays, and towed arrays feed into a combat system that was cutting-edge when these boats were built — and has only improved with upgrades.

In simple terms: if you were an enemy submarine commander in the 1990s or 2000s, Seawolf is the boat you really didn’t want to see show up on your trail.

And the Navy wanted 29 of them at sea.

How 29 Became 3

On paper, the Seawolf program looked straightforward in the early 1980s. Design a best-of-breed submarine to counter the latest Soviet attack and ballistic-missile subs, then build nearly thirty of them over a decade. The first boat, USS Seawolf (SSN-21), was laid down in 1989 — right as the geopolitical rug was being pulled out from under the program.

By 1991, the Soviet Union was gone. The Russian Navy was rusting at the pier. In Washington, the question shifted from “How fast can we get these?” to “Why do we still need this many?”

Seawolf also ran into sticker shock. Public estimates place the unit cost of the first two boats in the neighborhood of $3 billion apiece in then-year dollars, with the third, USS Jimmy Carter, even more expensive due to a 100-foot hull extension for special missions.

For budget hawks, that price tag was irresistible ammunition. Why keep buying a multi-billion–dollar Cold War super-sub when the enemy it was built to fight had imploded?

Navy leaders, under pressure to fund other priorities and show they were adapting to the new era, gradually walked the program back:

-First, the plan dropped from 29 boats to 12.

-Then, amid further cost pressure and arguments that the mission had changed, it dropped again — to just three hulls.

-Analyses of the program later pointed out the usual suspects in a first-of-class, high-end submarine: cost growth, schedule slips, and shifting requirements. All of that made Seawolf easy to caricature as a luxury at the exact moment when the political establishment wanted to cash in a peace dividend.

-In 1995, the hammer fell. Seawolf procurement was capped. The Navy would finish Seawolf, Connecticut, and one heavily modified special-mission boat, Jimmy Carter — and that was it.

-This cut was felt hard when I lived in Rhode Island, as I knew many people who lost their jobs at Electric Boat when the program was cut back. Many lost their homes and their financial freedom, and never found jobs that paid the same. I knew many friends who had to pull their kids out of college and borrow from their 401 (k) to survive until they could get back on their feet.

Twenty-six planned hulls disappeared with the stroke of a pen.

The Virginia-Class: Quantity Over Apex Capability

Killing the Seawolf line left a hole. The Los Angeles-class boats that Seawolf was supposed to replace were still going to age out. The Navy still needed attack submarines for everything from carrier escort to intelligence patrols and strike missions.

The answer became the Virginia-class: smaller, cheaper, more modular, and specifically optimized for a post–Cold War world where littoral operations, land-attack Tomahawks, and special operations support loomed large. Instead of a pure deep-ocean hunter, Virginia was built as a flexible “multi-tool” — still very capable, and far easier to afford in quantity.

In fairness, this pivot worked in many ways. Virginia-class production stabilized, the learning curve kicked in, and the program became something close to a model of how to do big undersea acquisition “right.” Navy and industry both took lessons from Seawolf’s difficulties and baked them into Virginia’s design and build process.

But that success came with a tradeoff. The Navy ended up with only three Seawolf-class submarines — the “apex predators” of the fleet — and a much larger but somewhat less extreme force of Virginias.

In an era where Washington assumed it would own the undersea domain indefinitely, that felt like a reasonable compromise.

The world did not stay in that era.

From the 1990s to Today: Living With a Self-Inflicted Shortage

Fast forward to the 2010s and 2020s, and the Navy’s attack submarine force is entering what planners politely call a “trough.”

The long-standing benchmark for SSNs has been a fleet of 66 boats. Even with strong Virginia-class production, official and independent analyses project the inventory dipping into the low 40s in the late 2020s and early 2030s, as large batches of 1980s-vintage Los Angeles-class boats retire faster than new Virginias can be delivered.

By the end of 2023, well over half of the original 62 Los Angeles-class submarines had been retired, with more decommissionings on the way. At the same time, Virginia-class construction has struggled to hit the Navy’s aspiration of two boats per year; the industrial base is still digging out from production and maintenance backlogs.

That leaves the Navy with:

-Three Seawolf-class SSNs.

-A gradually aging pool of Improved Los Angeles-class boats.

-A growing but still insufficient Virginia-class force.

In the middle of all that, the four converted Ohio-class guided-missile submarines — the SSGNs that can each carry well over a hundred Tomahawk missiles — are retiring by the end of the decade. Their departure takes a massive chunk of undersea strike capacity off the table just as China and Russia pose more serious naval challenges.

If there were 20-plus Seawolf-class boats in service as originally envisioned, this crunch would look very different. Each Seawolf can carry a heavy weapons load and operate in the most contested waters on earth. A flotilla of them in the Western Pacific or North Atlantic would give combatant commanders extraordinary flexibility and firepower.

Seawolf-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Instead, we have three.

The Maintenance and Workforce Squeeze

The story gets worse when you look at the maintenance and workforce side.

Submarines only matter if they can actually go to sea. The Government Accountability Office and outside analysts have been blunt: the submarine industrial base is understaffed and overstretched. By some estimates, the workforce in recent years has been roughly a quarter below what’s needed to meet both construction and maintenance demands, contributing to long delays and idle boats.

The now-famous case of USS Boise, a Los Angeles-class SSN that sat pier-side for years awaiting an overhaul, is a perfect example. The sub lost its dive certification in 2017 and will not return to service for more than a decade because public shipyards and private yards alike are backed up.

In this environment, every hull counts. When you are losing attack boats to retirement and to the maintenance queue faster than new subs hit the fleet, the decision to have only three high-end Seawolfs looks less like an accounting choice and more like strategic self-harm.

Those three Seawolfs, especially the uniquely modified Jimmy Carter with its multi-mission platform for intelligence and special operations work, are doing some of the Navy’s most sensitive undersea missions. But they cannot be in two places at once. They cannot backfill the sheer capacity shortfall created by decades of under-investment in both hull numbers and shipyard infrastructure.

(June 22, 2021) Seawolf-class fast attack submarine USS Seawolf (SSN 21) transits the Pacific Ocean, June 22, 2021. Seawolf is currently underway conducting routine maritime operations in U.S. 3rd Fleet. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Olympia O. McCoy)

China, Russia, and the World the Seawolf Was Built For

Here is the irony: the world the Seawolf-class was designed to dominate is back.

Russia may be weaker overall than the Soviet Union, but its attack submarine fleet is still capable and active, fielding improved nuclear boats and advanced diesel-electric subs that make life difficult in the North Atlantic and Arctic. China, meanwhile, is rapidly expanding and modernizing its submarine force, fielding new nuclear-powered attack and ballistic-missile boats and pushing them further into the Pacific.

This is the environment Seawolf was built for: a high-end undersea chess match against advanced Russian and Chinese submarines, with layered anti-submarine warfare from both sides.

Yasen-Class Submarine from Russia. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Instead of 29 apex predators, the U.S. Navy has three — and a looming attack-submarine shortfall that will bottom out at a level far below what planners say they need.

To be clear, the Virginia-class is an impressive design that continues to evolve. Block V boats with Virginia Payload Modules will partially compensate for the loss of the Ohio SSGNs’ missile magazines. But Virginia’s production rate is still behind the Navy’s own target, and the AUKUS commitment to supply Australia with several Virginia-class boats in the 2030s only adds strain to a system that is already struggling to hit two boats per year, much less more.

In that context, the decision to cap Seawolf at three hulls looks like the undersea equivalent of killing the F-22 Raptor line after building a small fleet and then watching competitors catch up.

The Long Shadow of a Short Program

The Seawolf program’s major flaw was not some deep technical defect. It was that the United States convinced itself it could walk away from apex undersea capability at scale because history had ended.

That choice reshaped the Navy in several ways:

It forced a pivot to a more “affordable” attack submarine design in Virginia, trading some high-end performance for cost and flexibility.

180709-N-KC128-1131 PEARL HARBOR (July 9, 2018) – Multi-national Special Operations Forces (SOF) participate in a submarine insertion exercise with the fast-attack submarine USS Hawaii (SSN 776) and combat rubber raiding craft off the coast of Oahu, Hawaii during Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise, July 9. Twenty-five nations, 46 ships and five submarines, about 200 aircraft, and 25,000 personnel are participating in RIMPAC from June 27 to Aug. 2 in and around the Hawaiian Islands and Southern California. The world’s largest international maritime exercise, RIMPAC provides a unique training opportunity while fostering and sustaining cooperative relationships among participants critical to ensuring the safety of sea lanes and security of the world’s oceans. RIMPAC 2018 is the 26th exercise in the series that began in 1971.` (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Daniel Hinton)

It left the service with a tiny cadre of Seawolf-class boats that carry a disproportionate share of the most sensitive missions.

It contributed, alongside broader budget and industrial decisions, to a 2020s–2030s landscape in which Los Angeles-class subs are retiring faster than Virginias can be delivered, with a trough in overall SSN numbers just as great-power competition returns.

Would 29 Seawolfs have fixed every problem? Of course not. The shipyards would still be strained. Maintenance would still be hard. Virginia would still be needed. But a fleet of even 10–12 Seawolf-class subs, let alone the full 29, would dramatically change the Navy’s options today — particularly in the Indo-Pacific.

Instead, the Navy is staring at a period in which it will be asked to do more undersea work with fewer attack boats overall and only a tiny handful of its most capable class.

The Lesson for the Future

The deeper lesson here is not “build more Seawolfs” — that line is gone. It’s that the United States cannot keep designing exquisite, world-beating systems and then buying them in boutique quantities on the assumption that history will stay quiet.

Seawolf was treated as an unaffordable luxury just as the Cold War ended. The Virginia program then had to claw back capacity in an era of constrained budgets and shrinking industrial skills. Now, with China and Russia back as serious maritime competitors and AUKUS adding new demands, we discover that you cannot surge attack submarines any more than you can surge shipyard workers.

Virginia-Class Submarine Cut Out. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The decisions made in the 1990s echo forward for decades.

As the Navy and Congress think about the next generation of attack submarines beyond Virginia — the so-called SSN(X) — they would be wise to treat the Seawolf story as a warning. Designing another “perfect” boat and then building only three or four would be the worst possible outcome.

The U.S. Navy did not make a mistake in building Seawolf. It made a mistake in building so few. That single flaw now shapes the undersea balance from the Barents Sea to the South China Sea — and it will keep shaping it as the Los Angeles-class bows out, the Virginia-class struggles to keep up, and three lonely Seawolfs carry far more weight than they were ever meant to bear.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.