Key Points and Summary – The USS United States (CVA-58) was conceived as an 82,000-ton, island-less supercarrier to launch nuclear-capable heavy bombers—four hulls planned, one keel laid.

-Five days later, in April 1949, Defense Secretary Louis Johnson canceled it, siding with the new Air Force’s claim to the strategic bombing mission and citing costs.

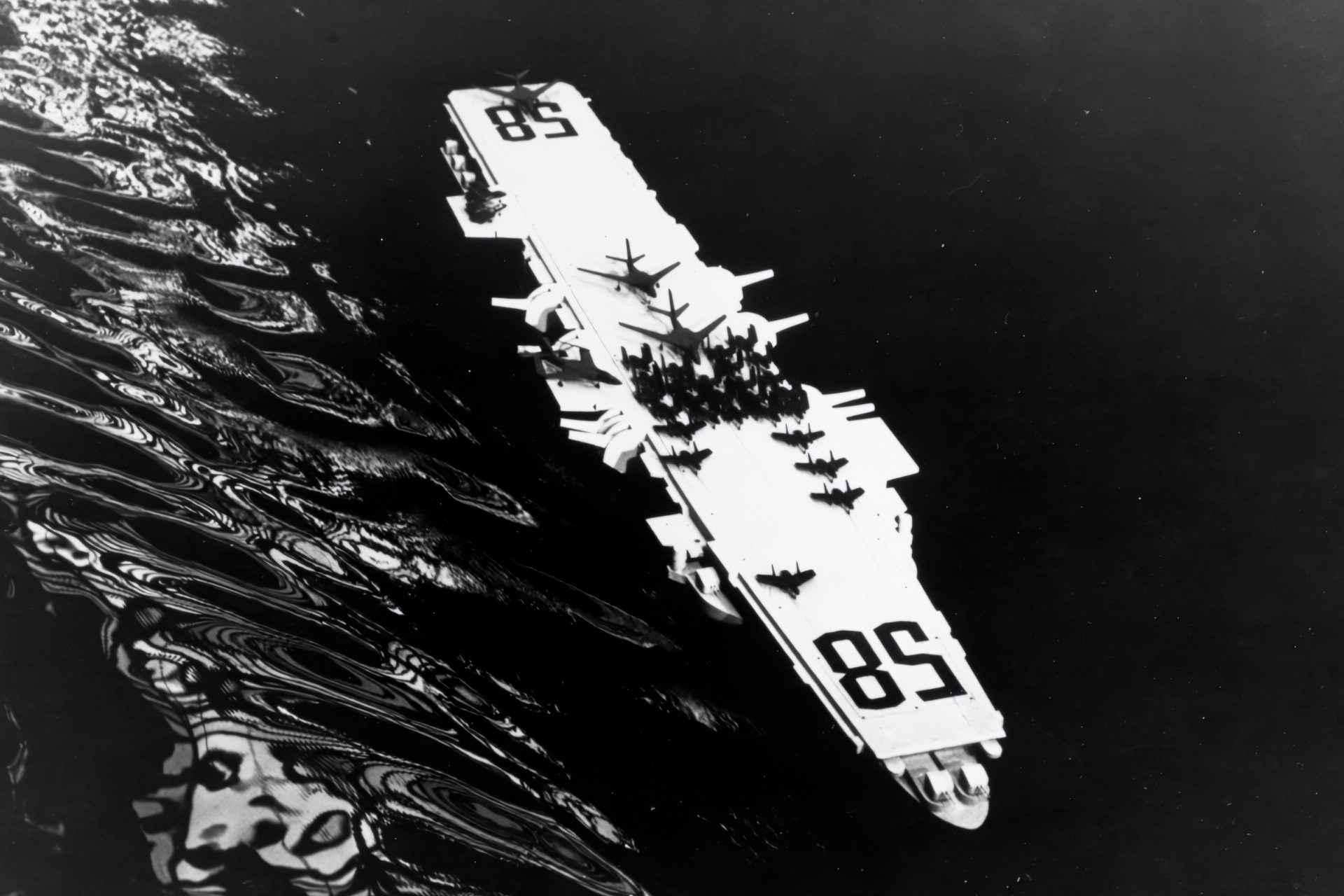

USS United States Aircraft Carrier U.S. Navy Photo. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-The decision ignited the “Revolt of the Admirals,” forced the Navy secretary’s resignation, and triggered congressional hearings. Advocates argued the design promised unmatched reach; critics flagged command-and-control challenges and duplication.

-A year later, the Korean War underscored the continuing need for carriers—proof that nuclear dominance alone couldn’t cover America’s conventional war demands.

The Ill-Fated Aircraft Carrier USS United States (CVA-58)

The USS United States (CVA-58) was a highly ambitious post-World War II U.S. Navy supercarrier designed to carry large bombers capable of delivering nuclear payloads.

The carrier was authorized in 1948, but it was short-lived. It suffered from several design flaws—notably the lack of an island, which would have made command and control very difficult.

The carrier was canceled five days after its keel was laid in April 1949 due to a combination of budget cuts and intense inter-service rivalry with the newly independent U.S. Air Force.

An Ambitious New Design

The United States entered the postwar years with the unquestioned best navy in the world. And the Navy championed the use of an enormous, 82,000-ton flat-decked aircraft carrier that could launch 16–24 heavy bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons, along with 80 escort fighters.

One of the leading proponents of the design was Adm. Marc Mitscher. Mitscher six years earlier had commanded the USS Hornet, which sailed to Japan and launched B-25 bombers—normally land-based—to bomb Japan just a few months after Pearl Harbor.

Mitscher was also renowned for his decision to “turn on the lights” during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, which allowed 200 aircraft to land on his carriers when they returned after dark.

The plan was to build four new carriers that would sail alongside other, smaller carriers. A pair of Essex-class carriers and a Midway-class carrier would carry extra fighters and other aircraft to complement the heavy bombers. These carriers would provide air defense for the carrier battle groups.

The lack of an island, a standard feature on all aircraft carriers, made the command and control of sorties more difficult, though it would also protect the carrier from an atomic blast that occurred within range.

The Navy was gutted after World War II, and the service was looking for ways to nevertheless influence an ocean war, even without the superlative number of ships it sailed in August 1945.

The Navy intended to build the four carriers one at a time each fiscal year, starting in 1949, with all of them operational by 1955. But during Senate Appropriations Committee testimony, Navy Secretary John L. Sullivan described the carrier as a “prototype” and said it was a “very great mistake” to build more of them until the first one was built and operated.

The Rivalry Between The Navy And the Air Force

The project became a focal point in the struggle between services for budget and influence in the new atomic age. The Air Force argued that strategic bombing was its responsibility and saw the carrier as a threat to that role—and the budget that went with it.

The Revolt of the Admirals, But The Air Force Had Political Clout

The new Air Force, created from the Army Air Corps, wasn’t content with being the new kid on the block. It was fighting for every piece of turf it could claim.

The Air Force was not only against this new flush-deck carrier, but also the Navy’s existing fleet carriers. In March 1949, Louis A. Johnson was named Secretary of Defense. The Air Force perceived the new leader as an ally and began to forcefully stake out its position.

Air Force Chief of Staff General Hoyt S. Vandenberg sent a memo to the outgoing Secretary, James Forrestall, defining in no uncertain terms the service’s position on the “supercarrier.” Bandenberg’s intent was “to prevent Congress” from further committing to approving the carrier.

USS Intrepid Essex-Class Aircraft Carrier. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

Essex-Class USS Intrepid Aircraft Carrier. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

The keel of the newly named United States was laid down at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company on April 18, 1949. But Johnson soon ordered the cancellation, agreeing with the Air Force that long-range bombers, such as those the carrier was designed to launch, were within the Air Force’s domain, and that a Navy-based strategic nuclear capability would be a duplication of resources.

Johnson said his decision came after “careful consideration and discussion of the matter with the president.” However, there is plenty of circumstantial evidence that such was not the case, and that Johnson never discussed the matter with the Navy, or with Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Dwight Eisenhower.

Johnson never stated a reason for canceling the ship, though it was purportedly a matter of cutting budgets. However, his real reason was that he saw the Navy’s desire for the big-deck carrier as a means of competing with the Air Force; while he was secretary of defense, “the Navy would have no part in long range or strategic bombing.”

The cancellation led to the “Revolt of the Admirals,” a public dispute between Navy and Air Force leaders. It also resulted in the resignation of the secretary of the Navy and congressional hearings to investigate the decision. During “The Revolt of the Admirals,” Johnson informed Adm. Richard Connolly:

“Admiral, the Navy is on its way out. Now, take amphibious operations. There’s no reason for having a Navy and a Marine Corps. General (Omar) Bradley … tells me that amphibious operations are a thing of the past. We’ll never have any more amphibious operations. That does away with the Marine Corps. And the Air Force can do anything the Navy can do nowadays, so that does away with the Navy.”

Was the cancellation of the USS United States a smart decision? Probably. But giving so much power to the fledgling U.S. Air Force was foolhardy.

One year later, the Korean War began, and it showed the folly of the Truman administration’s insistence on nuclear weapons as a uniquely capable war deterrent.

About the Author: Steve Balestrieri

Steve Balestrieri is a National Security Columnist. He served as a US Army Special Forces NCO and Warrant Officer. In addition to writing on defense, he covers the NFL for PatsFans.com and is a member of the Pro Football Writers of America (PFWA). His work was regularly featured in many military publications.

More Military

Russia’s Submarine Fleet Summed Up Simply in 4 Words

The Air Force Sent A-10 Warthogs to China’s Doorstep

The Air Force’s B-2 Bomber Nightmare Has Arrived

The Navy Tried for 4 Weeks to Sink Their Own Aircraft Carrier