Key Points and Submarine – In 1968, the Soviet ballistic-missile submarine K-129 sank in the Pacific, prompting the CIA’s ultra-secret Project Azorian.

-Using Howard Hughes’ purpose-built Glomar Explorer as cover for “deep-sea mining,” the Agency tried to lift the wreck from 16,500 feet with a massive underwater claw, all while evading Soviet scrutiny.

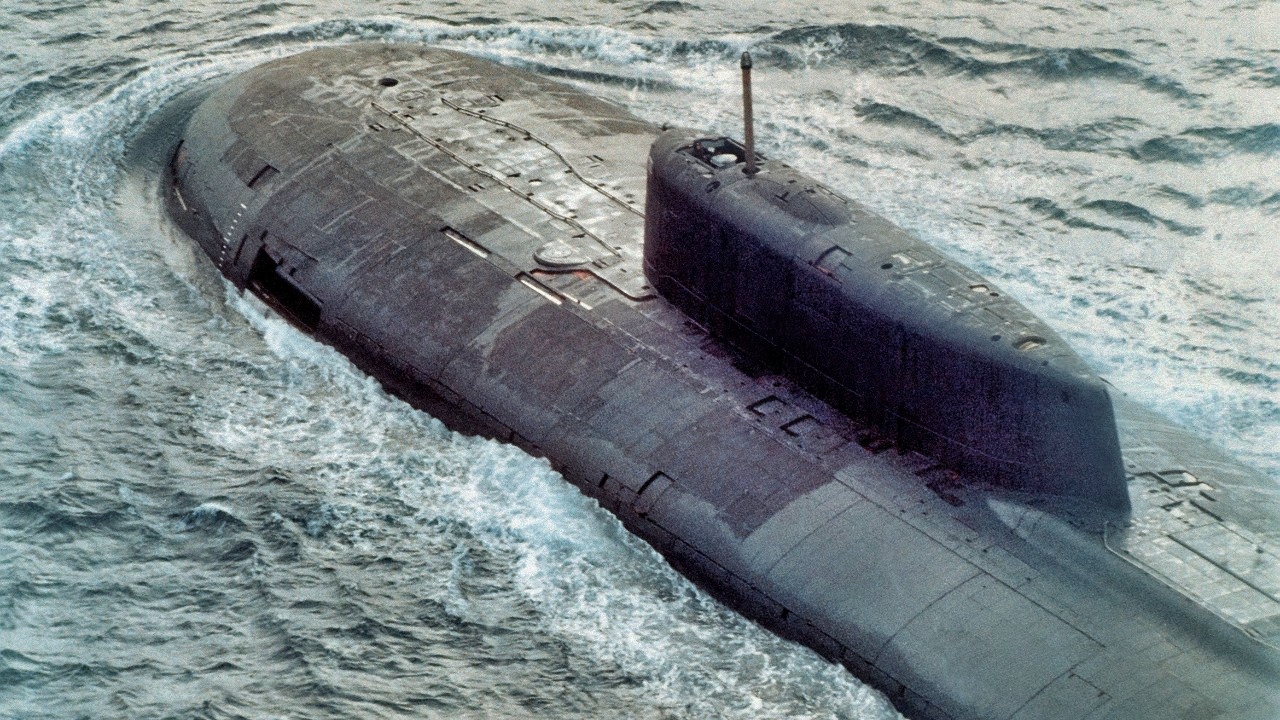

Akula-Class Submarine from Russian Navy. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-The 1974 recovery only partially succeeded, bringing up part of the hull and the remains of six sailors, who were buried at sea with full honors.

-A planned second attempt was scrapped after press leaks exposed the operation. Decades later, declassified files confirmed Azorian as one of the boldest intelligence feats of the Cold War.

Inside Project Azorian: The CIA’s Wild Plot to Steal a Soviet Sub

In 1968, at the height of the Cold War, a Soviet submarine called the K-129 sank to the floor of the Pacific Ocean. In 1974, the CIA launched a secret project called Project Azorian, aimed at pulling the submarine out of the ocean and obtaining whatever secrets could be found on it. But it wasn’t until 2010 that the full truth of the episode was declassified by the CIA.

“Imagine standing atop the Empire State Building with an 8-foot-wide grappling hook on a 1-inch-diameter steel rope,” the CIA says on its website in its description of the mission.

“Your task is to lower the hook to the street below, snag a compact car full of gold, and lift the car back to the top of the building. On top of that, the job has to be done without anyone noticing. That, essentially, describes what the CIA did in Project AZORIAN, a highly secret six-year effort to retrieve a sunken Soviet submarine from the Pacific Ocean floor during the Cold War.”

How It Happened

The K-129, the CIA said, was a Soviet Golf II-class submarine, which carried three SS-N-4 nuclear-armed ballistic missiles. It was to be based northeast of Hawaii, but it never made it to base. In 1968, the submarine and its crew were lost.

The U.S. soon discovered exactly where the wreck was.

“After the Soviets abandoned their extensive search efforts, the US located the submarine about 1,800 miles northwest of Hawaii on the ocean floor 16,500 feet below. Recognizing the immense value of the intelligence on Soviet strategic capabilities that would be gained if the submarine were recovered, the CIA agreed to lead such a recovery effort with support from the Department of Defense,” the CIA said.

An elevated port side view of the forward section of a Soviet Oscar Class nuclear-powered attack submarine. (Soviet Military Power, 1986) Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Oscar-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

In 1969, per the National Security Archive, the CIA established a Special Projects Staff within its Directorate of Science and Technology, under the leadership of senior official John Parangosky.

In August of that year, CIA Director Richard Helms placed that staff under what was described as a “special security compartment” called “Jennifer.” This was known only to, per the archive, “a very small and select group of people inside the White House and the U.S. intelligence community, including President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger.”

The CIA realized that it was a tall task to pull a submarine that large out of the ocean and to do it in secret. The plan ultimately decided upon was to “use a large mechanical claw to grasp the hull and a heavy-duty hydraulic system mounted on a surface ship to lift it.”

The machine used to do so was the Hughes Glomar Explorer, built over the course of about four years for those purposes by Howard Hughes’ company, under the cover of doing marine research and “mining manganese nodules lying on the sea bottom.”

Per the archive, there was doubt about the project and its chances, but “the only thing that saved the program from being terminated was the potential intelligence bonanza that would accrue if the project succeeded.”

The project took extra steps to remain stealth.

“To preserve the mission’s secrecy, the capture vehicle was built under roof and loaded into the ship from a barge submerged underneath,” the CIA article says. “With these special capabilities, the ship could conduct the entire recovery underwater, away from the view of other ships, aircraft, or spy satellites.”

In 1972, during the period of U.S./Soviet detente, there were thoughts that the program might need to be canceled, but Nixon ultimately agreed to move it forward.

A Big Lift

The actual salvage operations took place over more than two months in 1974, all the while being surveilled by “nearby Soviet ships curious about its mission.”

The salvage, though, only worked partially.

“When the submarine section was about halfway up, it broke apart, and a portion plunged back to the ocean bottom. Crestfallen, the Glomar crew successfully hauled up the portion that remained in the capture vehicle,” the CIA article said.

The mission did recover the bodies of six Soviet crewmen, who were given a burial at sea.

An Aborted Second Mission

The CIA planned to try again and salvage the rest of the submarine. However, the mission ran into trouble for a surprising reason: An office of the Hughes company in California was burglarized, with secret documents stolen, which exposed the CIA’s involvement with the Glomar project.

By early 1975, the cat was out of the bag, with the Los Angeles Times and later columnist Jack Anderson exposing at least part of the truth about the operation, as well as its ties to Howard Hughes. Andrerson, per the CIA account, reported that “Navy experts had told him the sunken submarine contained no real secrets and that the project was a waste of taxpayers’ money.”

While the government said nothing officially, the Soviets were now aware of the effort, and therefore the U.S. could no longer attempt to salvage what remained.

Alfa-Class Submarine Creative Commons Image.

Even though it couldn’t salvage most of the submarine, “the CIA considered the operation to be one of the greatest intelligence coups of the Cold War. Project AZORIAN remains an engineering marvel, advancing the state of the art in deep-ocean mining and heavy-lift technology,” the CIA account says.

After The Fact

According to the National Security Archive, that disclosure in 2010 revealed a lot more than what was previously disclosed, although significant parts of the document were redacted.

“Unfortunately, the CIA made significant deletions from the text of the article, which makes it extremely difficult to accurately gauge just how successful “Project Azorian” was,” the archives say. “For example, the CIA refused to declassify any information concerning the massive cost overruns, which threatened to shut down the program during its early stages. Subsequent reports estimate that as much as $500 million (in 1974 dollars) were spent.

“Nor did the declassified portions of the CIA article answer the critically important questions of how much of the submarine the Hughes Glomar Explorer managed to bring to the surface, or what intelligence information was derived from the exploitation of the portions of the sub that were recovered. Unfortunately, this material apparently was either redacted from the text or not included because of the high classification assigned to this material.”

In the early 1990s, after the Cold War was over, the CIA declassified a videotape of the Russian crew members’ burial at sea, and the videotape was reportedly presented to Russian President Boris Yeltsin.

“Internal evidence suggests that the article was written in 1978, but it was prepared at such a high level of classification that it was apparently unpublishable until the Agency made decisions in 1985 to downgrade it to ‘Secret,’’ the National Security Archive said.

About the Author: Stephen Silver

Stephen Silver is an award-winning journalist, essayist, and film critic, and contributor to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Broad Street Review, and Splice Today. The co-founder of the Philadelphia Film Critics Circle, Stephen lives in suburban Philadelphia with his wife and two sons. For over a decade, Stephen has authored thousands of articles that focus on politics, national security, technology, and the economy. Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) at @StephenSilver, and subscribe to his Substack newsletter.

More Military

The U.S. Navy’s Constellation-Class Frigate Crisis Keeps Getting Worse

China’s New H-20 Stealth Bomber Might Have a 10,000 km Range

Even Mach 3 Speeds Could Not Save the Titanium SR-71 Blackbird

The U.S. Navy’s New DDG(X) Destroyer Is Sailing Into Stormy Waters