Article Summary – China’s Aircraft Carriers: Useful—But Fewer, Humbler, Closer to Home

-China’s aircraft carriers make sense only when tailored to its near-seas problem set.

-Operating under a dense missile-and-sensor lattice, PLAN decks should serve as mobile sensor-and-shield nodes—not blue-water strike queens.

-The right force is three to four carriers, with air wings weighted toward AEW, electronic warfare, counter-air, and tankers, complemented by Type 052D/055 escorts.

-Fujian’s EM catapults enable KJ-600-class AEW and stealth fighters, extending combat air patrols and survivability inside the First Island Chain.

-Pursuing six-plus carriers buys prestige, not power; global presence demands logistics China hasn’t fully built.

-Until unmanned systems mature at scale, quiet utility—not deep strike—should define China’s carrier concept.

Air Wings as Shields, Not Swords: How China Should Use Its Aircraft Carriers

China is committed to carriers—Fujian’s September catapult launches and earlier twin-carrier patrols by Liaoning and Shandong make that plain—but do carriers actually make sense for the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)?

Yes, but only if fleet size, air-wing mix, and operating concepts are tailored to China’s distinctive problem set: contesting the near seas, deterring intervention across the first island chain, and surviving within the First Island Chain’s archipelago kill zone.

Read that way, carriers still make sense for the PLAN, but in fewer numbers than enthusiasts claim—and only if they sail with air wings weighted toward early warning, electronic warfare, and counter-air rather than deep strike, and are tasked with shielding missile ships and submarines instead of chasing blue-water glory or global power projection.

China’s Naval Stance on Aircraft Carriers

Seen through that lens, the first order of business is purpose. China’s near-term challenge is controlling air and sea space across the Bohai, Yellow, East, and South China Seas, as well as the seams that extend out to the first and parts of the second island chain.

That battlespace already benefits from mainland fighters and bombers, long-range surface-to-air missiles, and a deep magazine of anti-ship ballistic missiles.

Deck aviation is the swing variable. A carrier close to the fight can extend combat air patrols, park true airborne early warning where satellites and shore radars see only clutter, and keep surface groups alive under missile rain.

Fujian’s electromagnetic catapults matter because they can launch a KJ-600-class early warning aircraft and a stealthy J-35 or a catapult-capable J-15 from the same deck, turning the ship into a sensor-and-shield amplifier within China’s missile web, rather than its centerpiece.

The Large Signature of the Aircraft Carriers

Turn the picture around, and the limits appear. The same missile complex that gives Beijing theater leverage also punishes large signatures. Anti-ship ballistic missiles and growing long-range fires hold big decks at risk from well outside the first island chain.

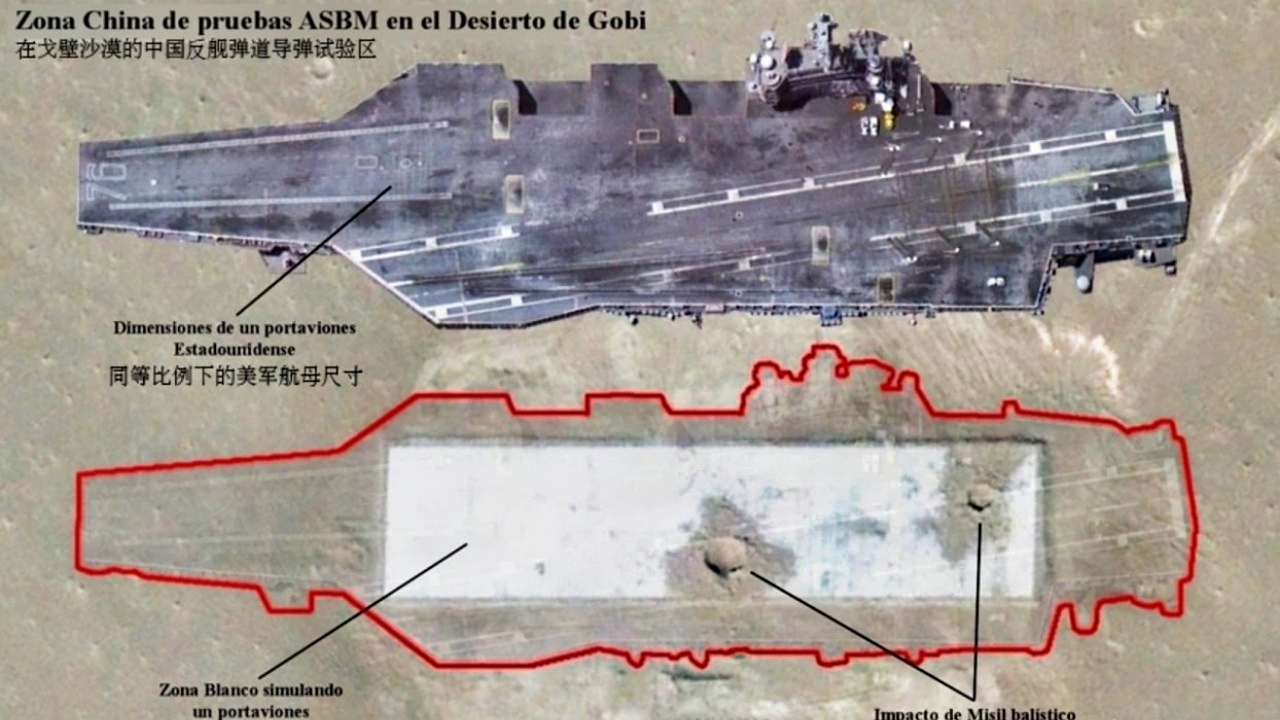

DF-26 China Missile Attack on Fake Aircraft Carrier Cut Out. Image Credit: Chinese Weibo Screenshot.

(Feb. 25, 2019) The aircraft carrier USS John C. Stennis (CVN 74) transits the South China Sea at sunset, Feb. 25, 2019. The John C. Stennis Carrier Strike Group is deployed to the U.S. 7th Fleet area of operations in support of security and stability in the Indo-Pacific region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Ryan D. McLearnon/Released)

Any adversary that fuses space, air, surface, and seabed sensors can threaten a carrier the moment it sails beyond Chinese air cover. Push a deck east of that umbrella, and survivability erodes quickly as magazines deepen and the sensor lattice thickens.

Force design follows from those realities. How many carriers fit the strategy China actually runs? Three to four.

Two workhorses to keep one available for training and presence, plus one or two catapult ships like Fujian to generate the early-warning-and-stealth air wing that keeps carrier aviation tactically relevant in the near seas.

That force lets the PLAN surge a dual-carrier package for a Taiwan or South China Sea crisis while preserving a third hull for maintenance and a fourth for experimentation. Beyond four, the returns diminish sharply.

Talk of six by the 2030s might sound impressive; divorced from geography, logistics, and survivability, it is a vanity metric.

Building the Air Wing

Missions define the air wing. If carriers are enablers rather than queens, their planes should reflect that. Build around early warning, electronic warfare, counter-air, and tanking to keep fighters on station and to sharpen the fleet’s picture. Keep strikes modest and largely opportunistic.

The goal is not to turn Chinese decks into American-style global strike platforms, but to make them the mobile nodes that thicken local control, close gaps in the sensor picture, and keep escorts and replenishment ships alive.

Escorts and integration matter as much as aircraft. The PLAN’s area-air-defense destroyers, notably the Type 052D and Type 055 classes, are the outer shield that catches what the carrier’s fighter screen misses. The shipboard radars and long-range surface-to-air missiles on these hulls must be thoroughly tested to the point of boredom in carrier air wing operations under realistic northern and western Pacific conditions. The measuring stick is simple: fewer surprises in the threat envelope and seconds shaved off kill chains when salvos come in heavy.

The Opposition Sets Its Defenses

Consider the opposition. Japan is deepening its anti-ship magazines and extending its reach across the Ryukyu Islands. The United States is dispersing airpower and practicing kill-web targeting that links any sensor to any shooter.

Taiwan is strengthening its bases and expanding its mobile missile batteries. The result across the Ryukyus–Taiwan–Luzon arc is an archipelago kill web—distributed sensors and shooters strung along chokepoints that attrit surface groups and punish large signatures.

In that environment, Chinese carriers are best suited to bolster local control where shore-based aviation is limited, rather than acting as independent strike platforms charging into the Philippine Sea.

Inside the South China Sea, the logic tilts even more toward restraint. Beijing leans on land-based power—bomber rotations and fighter detachments on built-up island runways—to project anti-ship reach without risking a deck.

Carriers complement that posture; they do not replace it. Used wisely, a PLAN carrier is the mobile node that stitches together mainland and outpost sensors, adds persistent airborne early warning, and provides the fighter screen that keeps area-air-defense destroyers and oilers alive.

Global Navy Ambitions

The global-navy temptation sits in the background. If Beijing wants a sustained presence in the Indian Ocean—escorting energy flows, protecting citizens abroad, shadowing US or Indian groups—more decks help with optics and scheduling.

However, that is a different strategy with different logistics: oilers and tenders in large numbers, secure basing in Djibouti and beyond, access to friendly ports, and sufficient trained pilots and maintainers to support more than one air wing at sea.

Even then, survivability against peer fires does not magically improve. A fourth hull might be justified to keep one forward while two posture near home; a fifth or sixth begins to purchase prestige more than power.

There is also a cautionary tale. Russia’s long struggle with Admiral Kuznetsov has underscored a core truth: navies get in trouble when they buy symbols. Moscow’s theory of victory relies on submarines, coastal aviation, and missile bastions, rather than blue-water flight decks.

China’s map is different—more trade exposure, contested islands, and longer supply lines into the Indian Ocean—but the lesson still stands. Buy the tools your war plan actually uses.

Technology tilts the balance but does not erase the fundamentals. Carrier utility rises if the air wing shifts toward survivable unmanned systems: endurance tankers and scouts that stretch combat air patrols, attritable strike drones that can soak losses, and electronic-attack platforms that blind parts of the opposing kill web.

China is moving in that direction, and so are its neighbors. Until those systems mature in numbers, the prudent use case remains simple: carriers as mobile sensors and shields that amplify the land-based missile complex, rather than being the tip of the spear.

The Bottomline: How China Could Leverage Aircraft Carriers

All of this returns to the opening question. Do aircraft carriers make sense for the PLAN in the missile age?

Yes, but fewer, humbler, and used in a different way. Three to four decks give Beijing presence and tactical elasticity without dragging the PLAN into a ruinously expensive race it cannot win against physics, geography, and an archipelago kill web purpose-built to murder surface ships.

If Beijing keeps that discipline—tuning fleet size, air wings, and concepts to real missions in the near seas—the aircraft carriers it already has will matter precisely because they will not need to prove it in a shooting war.

In an age of missiles and sensors, quiet usefulness is the most accurate measure of maritime power.

About the Author: Dr. Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a Senior Washington Fellow with the Institute for Peace and Diplomacy, a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities, and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. You can follow him on X: @aakatham. He writes a daily column for the National Security Journal.

More Military

Thrust Vectoring 101: The Jet Trick That Bends Physics—and Dogfights

The Big F-20 Tigershark Fighter Program Mistake Still Stings

2025: The Year America and Venezuela Go to War?

Forget China’s J-50: U.S. 6th-Generation NGAD Fighters Flew Back in 2019

Jim

October 5, 2025 at 8:08 pm

Rumors are surfacing, there is talk, U. S. Naval Command has thrown up their hands at the defense of Taiwan and quietly put tactical nukes on the table in a “second line of defense.”

If there is an overwhelming Chinese offensive.

This is wrong, if there’s anything to the reports.

But it shows how out of balance these “planners” are.

Taiwan is a postage stamp compared to China.

What are we doing?

Make a sustainable arraignment which avoids a terrible war which there is no reason for.