We Have a B-21 Raider Numbers Problem: Article Summary

-The B-21 Raider is supposed to be the backbone of America’s future bomber force, with the Air Force planning to buy about 100 aircraft.

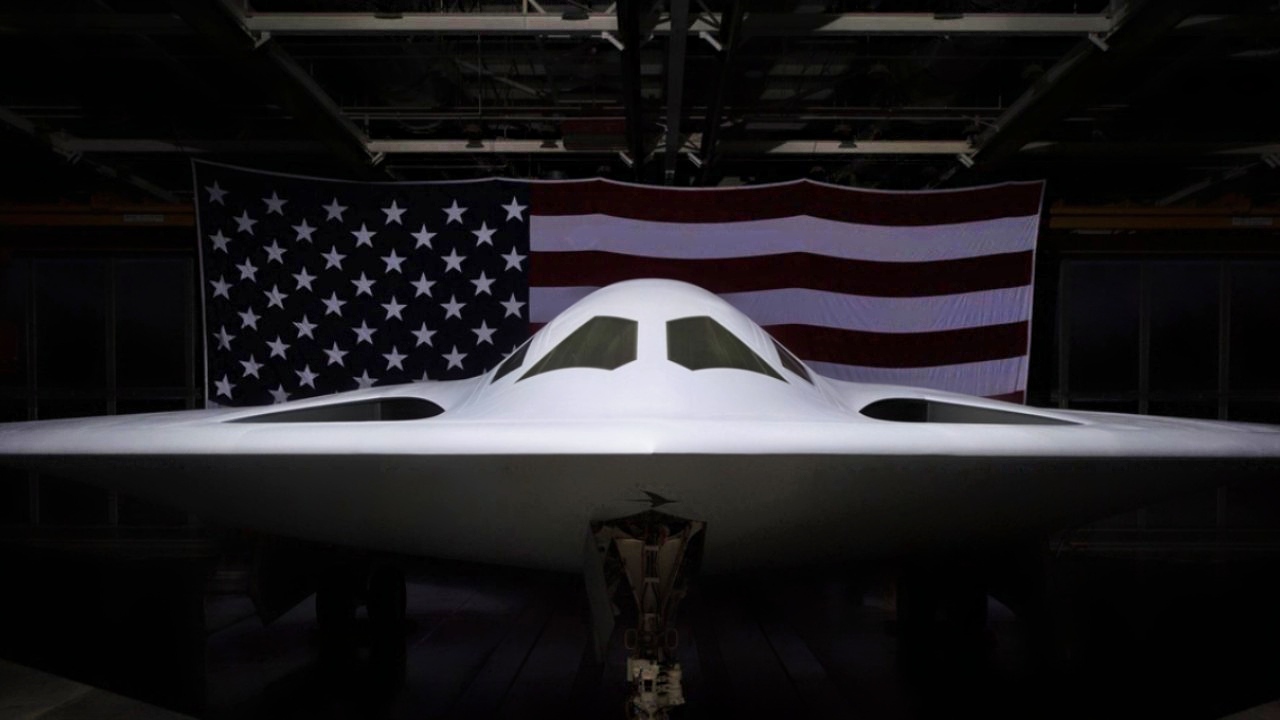

B-21 Raider Bomber. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-That sounds impressive until you stack it against a world in which China and Russia are both serious, simultaneous problems.

-The current bomber inventory is small, old, and fragile. B-2s and B-1s are limited, and the B-52J program could be delayed, curtailed, or even canceled if cost and schedule problems grow.

-If Washington is serious about long-range strike in a great-power era, the target should not be 100 B-21s. It should be 150–200.

Military service members, veterans, and citizens of Guam gathered for the Memorial Day Commemoration at the Guam Veterans Cemetery. The Ceremony consisted of a fly over from a B-52H Stratofortress, a musical performance from the Guam Territorial Band & Cantate, guest speaking from the honorable Eddie Baza Calvo, a Fallen Soldier Gravesite Tribute, and the playing of Taps. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Jacob Snouffer/Released)

The Backbone Bomber We’re Already Undersizing

On paper, “100 B-21 Raiders” sounds like a lot.

A hundred stealth bombers, each able to slip into heavily defended airspace, carrying nuclear or conventional weapons, flying from bases in the American heartland to targets in either Europe or Asia — that feels like a serious answer to China and Russia.

The problem is that “on paper” isn’t where wars are fought.

Right now, the U.S. Air Force talks about at least 100 B-21s as the plan.

Senior officials are already quietly admitting they may need more, but the number hasn’t moved. At the same time, the service is trying to nurse along a tiny B-2 fleet, a tired B-1B force, and a B-52 re-engining program that keeps sliding to the right.

If the United States is serious about a world with two nuclear-armed peer competitors, the conversation shouldn’t be whether 100 B-21s is enough.

It should be how to get to 150–200.

And if the B-52J program ever falters or gets canceled, that higher number becomes less a wish list and more a bare minimum.

What the B-21 Is Actually Meant to Do

The Air Force has been clear about the Raider’s job: it’s the penetrating, dual-capable stealth bomber that will form the backbone of the future bomber force, alongside standoff B-52s.

It’s built to go where fighters and non-stealthy bombers cannot — into the teeth of Chinese and Russian integrated air defenses, hitting hardened targets, mobile launchers, command bunkers, and critical infrastructure.

Think of it as the first real “China-designed” bomber the U.S. has ever built. The B-2 was optimized for the late Cold War, then did good work in Iraq, Serbia, and Libya. The B-21 is being tuned for the Western Pacific and a resurgent Russia: longer range, lower signature, open-architecture avionics for rapid upgrades, and the ability to carry whatever next-generation weapons the United States can field.

The current plan: buy roughly 100 B-21s by the mid-to-late 2030s, then let them and a modernized B-52J fleet carry the bomber mission for decades.

That sounds tidy. Reality is messier.

B-21 Raider. Image Credit: U.S. Air Force.

A Small, Aging Bomber Force

Start with what the Air Force actually has today.

The heavy bomber fleet is three types: B-52H, B-1B, and B-2A. On paper, there are a bit more than 140 aircraft total. In practice, fewer than that are combat-coded at any given time, and even fewer are available on a given day once you subtract jets in deep maintenance, upgrades, or long-term depot work.

A B-1B Lancer aircraft from the 34th Bomb Squadron departs from Al Udeid Air Base, Qatar, April 8, 2017. This departure marks the airframe’s first mission in the U.S. Air Force Central Command’s area of operations in more than two years. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Joshua Horton)

The B-2 fleet is tiny — only 21 airframes were ever built and one was lost in an accident. Those jets are precious, maintenance-intensive, and increasingly being treated as a bridge to the B-21 rather than a growth fleet.

The B-1B force has been pushed hard since Desert Storm. Structural fatigue, heavy use in low-threat wars, and a complicated maintenance picture mean it’s not the force it once was. Congress and the Air Force have already agreed to retire a chunk of the B-1 inventory; more will follow as the B-21 comes online.

That leaves the B-52 — and here is where things get interesting.

The Air Force is in the middle of a major effort to turn old B-52Hs into “B-52Js” by re-engining them, fitting new radars, and integrating modern weapons, potentially pushing their service lives into the 2050s. But the upgrade programs are slipping. Engine integration and radar modernizations have seen delays and cost growth. The bomber that is supposed to be the steady, standoff partner to the B-21 is not guaranteed to glide smoothly into its second century.

In that context, a 100-plane B-21 fleet stops looking generous and starts looking thin.

Why 100 Raiders Won’t Be Enough

A little simple math helps.

A fleet of 100 B-21s will not mean 100 combat-ready bombers on call. A realistic mission-capable rate in a high-end fleet might be 70 percent on a good day, and not all of those will be combat-coded; some will be dedicated to test, training, or operational evaluations. In a real shooting war, you might be able to count on 60–70 Raiders actually available for combat at any given moment. The rest are in maintenance, recovering from hard sorties, or being turned around.

Now split those 60–70 aircraft between theaters.

If you have a serious crisis with China and Russia at the same time, or if one great-power fight drags on while another theater heats up, you quickly find yourself making ugly choices. Does Indo-Pacific Command get two-thirds of your penetrating bombers and Europe one-third? What happens when a jet is damaged or lost and can’t be replaced for years? What if a base comes under missile attack and you lose parking spots, fuel lines, or maintenance hangars?

Attrition is not hypothetical. In a sustained war against a peer, you are going to lose aircraft — to accidents, to enemy action, to simple bad luck. The whole point of the B-21 is to make those losses rarer, but nothing is invulnerable. If you start with 100 and you lose 10–15 over the course of a long conflict, your fleet shrinks fast.

A bomber is not a missile. You can’t surge production from zero to dozens a year overnight. You either build in margin up front or you accept that your striking arm will get thinner every year a major war goes on.

The B-52J Wild Card

So far, all of this assumes the B-52J program more or less works.

But say it doesn’t. Say engine delays deepen, costs blow out further, or the Air Force finds itself forced to trade fleets to pay for other priorities — fighters, tankers, space, cyber, you name it. The B-52 has survived multiple “last rites” before, but politics and budgets are ruthless. A truncated or canceled B-52J effort would leave the B-21 almost alone as the heavy bomber of record.

That scenario is not my prediction. It is the kind of risk any serious planner has to stare down.

A U.S. Air Force B-1B Lancer assigned to the 34th Expeditionary Bomb Squadron, Ellsworth Air Force Base, South Dakota, flies over the United States, July 2, 2025. The B-1B is a heavy bomber with up to a 75,000 pound payload. (U.S. Air National Guard photo by Airman Spencer Strubbe)

If that happens and you have only 100 Raiders, you’ve backed yourself into a corner. You will not have the mass of airframes you need to sustain nuclear and conventional alert, plus forward presence, plus training, plus attrition reserve. You will be one bad week — a runway cratered here, a hangar hit there — away from a dangerously thin force.

If, instead, you are already on a path to 150–200 B-21s, losing or shrinking the B-52J program becomes painful but manageable. The Raider fleet can absorb more of the day-to-day burden and still preserve a margin for real war.

The Industrial Window Won’t Stay Open

There is another reason to think bigger now: the factory.

By all public accounts, the B-21 program has avoided the worst acquisition sins. It has stayed roughly on cost and schedule, with flight testing starting and the first production jets already in the pipeline. The contractor and the Air Force have built an industrial base around a low-observable bomber that is actually functioning.

That kind of industrial alignment is rare. It also doesn’t last forever.

Northrop Grumman and its suppliers can build more Raiders faster if they get a clear signal now that the Air Force wants 150–200 jets, not just 100. The head of Air Force Global Strike Command has already said the capacity exists to ramp up production; the limiting factor is demand and money, not factory space.

Former and current senior officials have hinted that 100 may be “insufficient for the future” and that they are at least exploring the cost of a larger fleet.

If Washington waits until the last Raider in the original buy is rolling off the line to decide it really wants more, it will be too late. Suppliers will have wound down. Skilled workers will have moved on. Restarting or expanding production will cost more and take longer.

This is the moment to lock in a bigger number, while the line is hot and the design is stable.

A Bomber Force Built for the World We Actually Live In

The world the United States faces now is not the unipolar 1990s or even the messy but lopsided 2000s. It is a world where China fields serious long-range strike, base-killing missiles, and growing air and naval power in the Western Pacific; where Russia is willing to launch major wars in Europe and still modernize its own strategic forces; and where both can stretch American attention and resources at the same time.

In that world, a small, exquisite bomber fleet is a liability, not an asset.

A U.S. Air Force B-52 Stratofortress, assigned to the 2nd Bomb Wing, receives fuel from a KC-135 Stratotanker, assigned to the 340th Expeditionary Air Refueling Squadron, during a multi-day Bomber Task Force mission over Southwest Asia, Dec. 10, 2020. The B-52 is a long range bomber with a range of approximately 8,800 miles, enabling rapid support of Bomber Task Force missions or deployments and reinforcing global security and stability.(U.S Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Joey Swafford)

The answer is not to build a thousand B-21s or bankrupt the country chasing some perfect number. It is to recognize that “about 100” is an arbitrary legacy planning figure, not a requirement handed down from Mount Sinai.

If the Air Force truly sees the Raider as the core of its future long-range strike, then 150–200 airframes is the scale you need to deter, to fight, and to ride out losses in a sustained campaign.

Especially if the B-52J stumbles, the case writes itself. The only way to ensure that America has a bomber force matched to a two-peer world is to size the B-21 program for that world now — not after the shooting starts.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.