Key Points and Summary – The X-43A was a moonshot on a shoestring: three tiny, hydrogen-gulping darts flung off a B-52 and a Pegasus booster to prove a scramjet could really breathe at hypersonic speed.

-After one failure, two flights in 2004 wrote history—Mach 6.8, then Mach 9.6—for only a handful of powered seconds.

-Then the program wrapped. Tragic? Not really.

Was Ending the Mach 9.6 X-43A Program a Mistake?

Only the “certified smart” engineers at NASA could come up with this aircraft. The unmanned X-43A Hyper X was a hypersonic experimental technology demonstrator that was one of the fastest planes of all time, traveling at an astonishing Mach 9.6.

It utilized scramjet power to slice through the air at an ultra-high speed. NASA spent eight years and $230 million on the Hyper-X program. This was one of the first hypersonic airframes in U.S. history.

It was initially tested in 2001 and carried by NASA’s NB-52B “mothership” airplane, accompanied by a Pegasus rocket booster from the Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards, California. In 2004, the X-43A reached Mach 6.8, and later that year, it hit nearly Mach 10.

This was after scientists had worked for many years on hydrogen-fueled air-breathing scramjet propulsion. However, work on the X-43A was later halted, and that may have been a mistake. Here is the story of the MACH 9.6 aircraft.

Let’s Learn More About the X-43A

The Hyper-X program began in 1996. The NASA engineers and technicians had tested scramjet flight in numerous simulations in wind tunnels and other evaluation methods. Three X-43A technology demonstrator aircraft were produced.

These were nearly 13 feet long. NASA wanted to fly the first two at MACH 7 and the third at MACH 10 velocity to set a Guinness World Record. Scientists couldn’t believe what they had on their hands.

This was the infancy of hypersonic flight, and NASA was poised to be at the forefront of future flight with hypersonic missiles and airplanes that could reach twice the speed of the Mach 5 barrier.

What Happened During the First Test?

The airships were fueled by gaseous hydrogen. This was a departure that needed to be fully evaluated before the first flight. The 2001 test of the X-43A was not successful. NASA personnel lost control of the booster rocket, and it failed to launch. Evaluators determined that it needed to self-destruct. The booster had a faulty control mechanism due to sub-optimal design.

The Results Were Greatly Improved Four Years Later

However, they continued to work out the kinks until the positive tests in 2004. This set a record for air-breathing craft flying at 110,000 feet. The X-43A pioneered the use of thermal shields to counteract the heat generated.

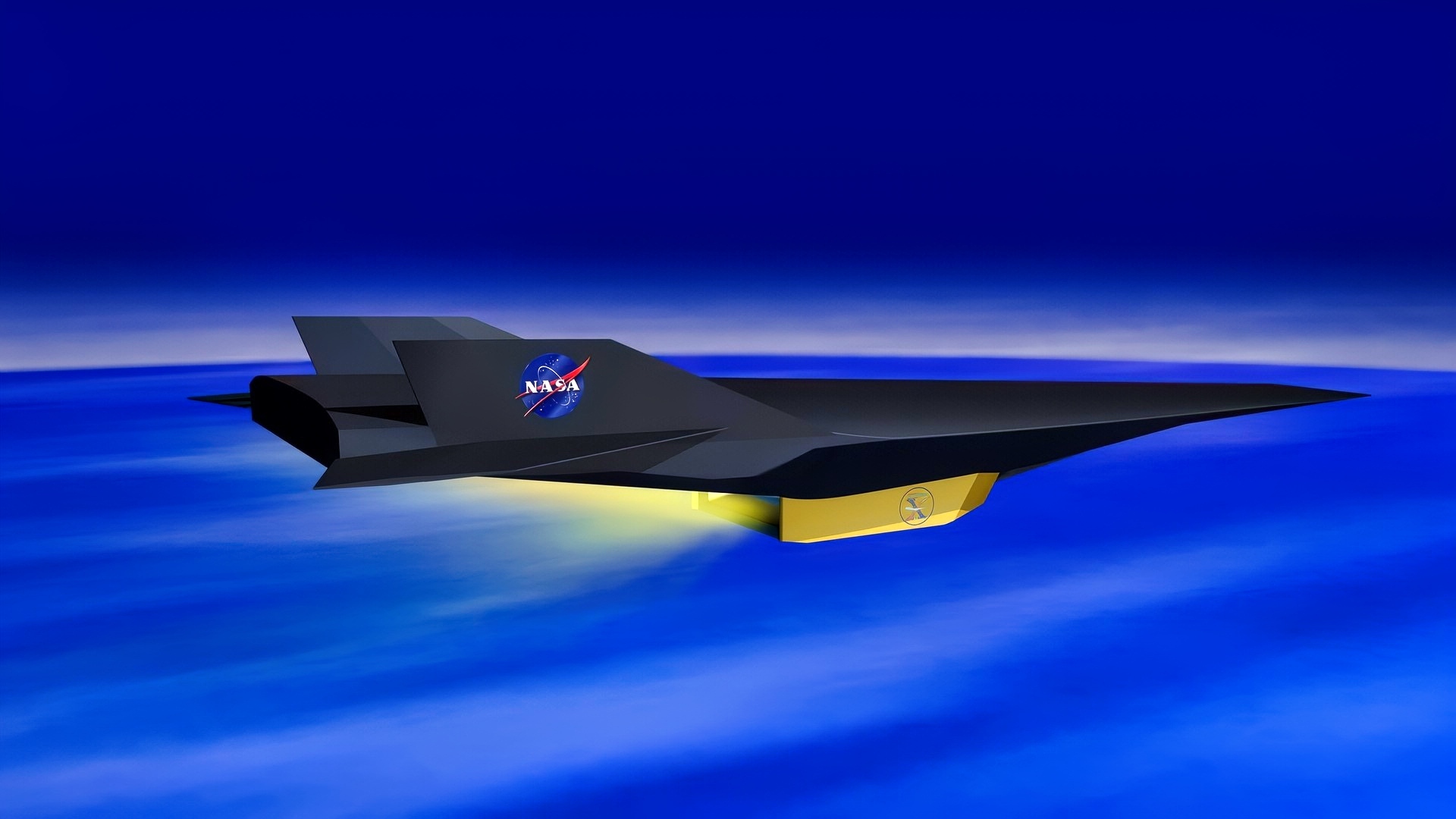

X-43A NASA. Image Credit: NASA.

The tests were executed over the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Southern California. The B-52B ascended to 40,000 feet, released its payload, and then its booster took it up to an additional 70,000 feet. The scramjet produced a multitude of hypersonic flight data for the researchers to analyze. This was an exciting time to be at the forefront of ultra-high-speed propulsion.

X-43A: The Future of the Program Looked Bright with Many Applications

What would the X-43A be used for? Could it become a nuclear-tipped cruise missile? Could the scramjet power a reconnaissance craft like a MACH 10 SR-71 Blackbird? What if it could be a bomber that could reach Russia or China in record speed? These were all exciting scenarios.

However, each aircraft fell into the water after the test and was never recovered. This was a mistake because it left much of the aircraft’s potential still undiscovered. The NASA personnel acquired about ten seconds of hypersonic flight data, but would this be enough to create a new aircraft that could revolutionize flight?

The X-43A succeeded in creating a wealth of information that could be used for future aircraft, despite the test burn and airborne time aloft being only a few seconds.

The X-43A program was not necessarily cancelled; it just ended by meeting its initial expectations. It was later folded into the X-51A demonstrator.

The X-43A project could be considered an initial success and should have paved the way for more flight testing at MACH 10 to integrate the scramjet on additional aircraft. That didn’t happen. The objectives were limited, as they had to be boosted and were never fully recovered.

It did not fly like a regular airplane – it used fuel like a spacecraft conducting a burn to escape Earth’s orbit.

More experimental hypersonic tests were needed to reach speeds of even Mach 5. Since the X-43A could fly twice the speed of sound, it was seen as a near miracle in flight.

Summed Up in 4 Words: Program Ended Too Early?

What if NASA had extended the X-43A program to create scramjets on manned aircraft or developed it into some weapon?

The short-lived X-43A could be seen as failing to create a platform for warfare. However, NASA, as a civilian agency, did its job.

More tests for the X-43A would have needed DARPA to step in and create new airframe concepts.

Then the Department of Defense would have to put the project out to bid along with NASA. Perhaps Lockheed Martin’s Skunk Works could have picked up the baton and run with it.

Congress would have needed to allocate more dollars for research and development, and the presidential national security team would need to be on board.

This concept didn’t come to fruition, but it was an exciting idea that demonstrated the Americans’ ability to produce such an air vehicle, inspiring further research into hypersonic flight.

MACH 10 is something that could have created a super weapon and could have been integrated into other aircraft at earth-shattering speed.

We can only hope the United States can replicate that velocity again.

About the Author: Brent M. Eastwood

Brent M. Eastwood, PhD is the author of Don’t Turn Your Back On the World: a Conservative Foreign Policy and Humans, Machines, and Data: Future Trends in Warfare plus two other books. Brent was the founder and CEO of a tech firm that predicted world events using artificial intelligence. He served as a legislative fellow for US Senator Tim Scott and advised the senator on defense and foreign policy issues. He has taught at American University, George Washington University, and George Mason University. Brent is a former US Army Infantry officer. He can be followed on X @BMEastwood.

More Military

Trump Wants a U.S. Navy Battleship Comeback: Reality Has Other Ideas

Ukraine Makes a Bold Claim: Putin Could Attack Another Country

Russia’s Su-34 ‘Fighter Bomber’ Is Getting Blasted Out of the Skies Above Ukraine

Boeing X-32 vs. YF-23 Black Widow II Stealth Fighter: Who Wins Summed Up in 4 Words

Jeff

October 1, 2025 at 8:07 am

Hey Brent,

The end of your story is somewhat incorrect. Yes, the “A” program met its objectives and met its natural end, but work on follow-on flights was well on its way. The Next Generation Launch Technology (NGLT) Program at NASA MSFC had a roadmap for airbreathing hypersonics that included “B”, “C”, and “D” variants of the X-43, each to explore different aspects of hypersonic flight and technologies, all leading up to a large scale demonstrator (think SR-72 that’s in the news so much). NASA was well on its way to flying the “C” vehicle with its Air Force partners (nearing CDR) when NGLT (and with it all hypersonics) was cancelled in 2004 so “we could return to the moon” with Constellation. 20 years later, still not back to the moon but we would have flown a large, reusable TBCC aircraft by now.