Key Points and Summary – China has spent decades building an anti-ship missile arsenal designed to hold U.S. aircraft carrier strike groups at risk across the Western Pacific.

-DF-21D and DF-26 “carrier killers,” YJ-18 and YJ-21 cruise and hypersonic missiles, and the DF-17 glide vehicle form the backbone of a dense A2/AD network supported by satellites, radars, and UAVs.

DF-17 Missile from China. Image Credit: PLA.

DF-17 Missile from China. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-The U.S. Navy counters with Aegis, SPY-6, SM-6 and SM-3 interceptors, electronic warfare, and close-in defenses—but magazine limits and cost make saturation salvos a serious danger.

-In any protracted Pacific fight, China’s range and numbers advantage could severely test U.S. naval air defenses.

The U.S. Navy’s Aircraft Carriers Have a Missile Problem

China has spent decades building an anti-ship missile arsenal designed to hold U.S. carrier strike groups at risk across the Western Pacific.

DF-21D and DF-26 “carrier killers,” YJ-18 and YJ-21 cruise and hypersonic missiles, and the DF-17 glide vehicle form the backbone of a dense A2/AD network supported by satellites, radars, and UAVs.

The U.S. Navy counters with Aegis, SPY-6, SM-6 and SM-3 interceptors, electronic warfare, and close-in defenses—but magazine limits and cost make saturation salvos a serious danger. In any protracted Pacific fight, China’s range and numbers advantage could severely test U.S. naval air defenses.

For decades, China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has been developing its weaponry with the sole purpose of eventually challenging the U.S. Navy. A key element is China’s development of anti-ship missiles. From hypersonic ballistic missiles to ship-launched subsonic cruise missiles, China possesses potentially the world’s largest inventory of anti-ship missiles, outpacing the U.S. and Russia. But how much of a threat do these missiles pose to the U.S. Navy, and how might the U.s. counter them?

An Introduction to China’s Missile Inventory

China’s anti-ship missile arsenal is the backbone of its anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategy. A2/AD is designed to deter or delay U.S. intervention in the Western Pacific, particularly during scenarios involving Taiwan or disputes in the South China Sea. At the center of this capability sit several advanced missile systems.

The DF-21D, often called a “carrier killer,” is a medium-range ballistic missile with a range of roughly 1,500-2,150 kilometers. It features a maneuverable re-entry vehicle and terminal radar guidance, thanks to which it can strike moving vessels at speeds approaching Mach 10.

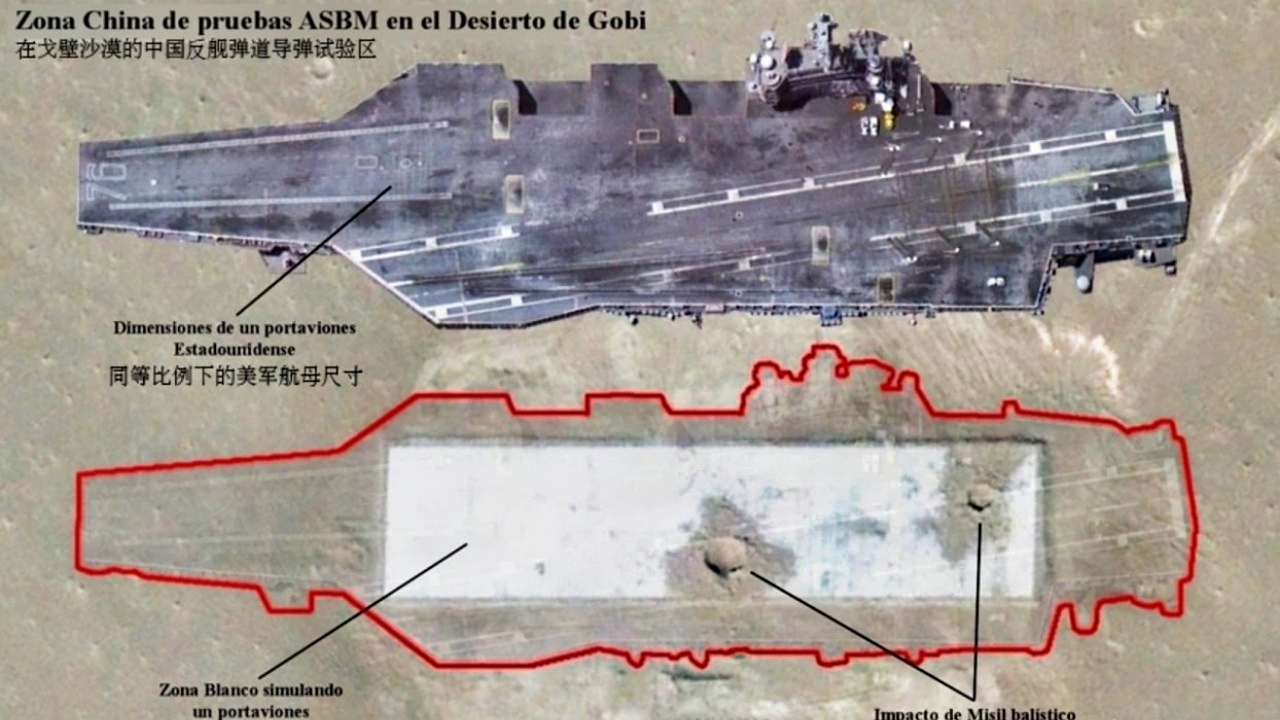

DF-26 China Missile Attack on Fake Aircraft Carrier Cut Out. Image Credit: Chinese Weibo Screenshot.

Complementing this is the DF-26, an intermediate-range ballistic missile with a reach of about 4,000 kilometers. Its anti-ship variant, the DF-26B, has been tested against moving targets and extends China’s strike capability deep into the Philippine Sea, threatening U.S. carriers at distances once considered safe.

China also possesses a large stockpile of anti-ship cruise missiles. The YJ-18, a subsonic cruise missile with a supersonic terminal sprint, has a range of up to 540 kilometers and can be launched from surface ships and submarines. Its sea-skimming profile and terminal acceleration make interception extremely difficult.

More recently, China has introduced the YJ-21, a hypersonic anti-ship missile reportedly capable of exceeding Mach 10 in its terminal phase, straining missile defense systems’ ability to intercept it. Additionally, the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle, with a range of 1,800 to 2,500 kilometers, adds unpredictability and penetration capability against traditional defenses.

These weapons are supported by a sophisticated reconnaissance-strike complex that includes over-the-horizon radars, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance satellites, and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. These assets can target moving ships in real time.

Why the U.S. Should be Concerned

China’s military doctrine emphasizes salvo-based saturation attacks to overwhelm U.S. defenses. Its distributed missile inventory of land-based launchers, surface combatants, submarines, and bombers creates a layered threat environment.

The DF-21D and DF-26 provide long-range standoff capability, while YJ-series missiles enable close-in strikes from multiple vectors. This combination of ballistic, cruise, and hypersonic missiles threatens the survivability of U.S. Carrier Strike Groups and forward bases. These capabilities have serious ramifications for the U.S. Navy. They reduce freedom of maneuver within the first island chain, push the risk envelope into the Philippine Sea, and suggest potential attrition rates unseen since World War II if defenses fail against hypersonic salvos.

U.S. Missile Defense Capabilities: Are They Enough?

To counter these threats, the U.S. Navy relies on a layered missile defense architecture that integrates kinetic interceptors, Electronic Warfare (EW), and emerging directed-energy systems. The Aegis Combat System directs the defense, incorporating SPY-6 radar, SM-series interceptors, and advanced fire-control algorithms. Recent tests, such as of the FTX-40 “Stellar Banshee,” demonstrated detection and simulated engagement of hypersonic targets.

The Standard Missile family plays a critical role: the SM-2 and SM-6 provide multi-role interception for air and missile threats, while the SM-3 offers exo-atmospheric intercept capability against ballistic missiles. The SM-6 Dual II variant enhances performance against maneuvering targets, including hypersonics.

Close-in defense is provided by systems like Phalanx close-in weapon system and SeaRAM, which combine sensors and short-range interceptors for last-ditch protection.

EW assets such as EA-18G Growlers, add jamming capabilities against missile seekers, while decoys and soft-kill measures complement hard-kill interceptors. Emerging technologies, including directed-energy weapons and hypersonic defense upgrades for Aegis and SPY-6, are under development to address future threats.

A U.S. Navy EA-18G Growler assigned to the USS Carl Vinson breaks away from a U.S. Air Force KC-135 Stratotanker from the 909th Air Refueling Squadron after conducting in-air refueling May 3, 2017, over the Western Pacific Ocean. The 909th ARS is an essential component to the mid-air refueling of a multitude of aircraft ranging from fighter jets to cargo planes from different services and nations in the region. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman John Linzmeier)

Hitting Where it Hurts: China’s Offensive Advantages

China currently holds the offensive advantage in missile range and speed. The DF-26’s 4,000-kilometer reach and the DF-21D’s maneuverability outclass the defensive range of U.S. interceptors such as the SM-6, which tops out around 370 kilometers.

While U.S. systems are improving, they remain vulnerable to saturation attacks and maneuvering hypersonic missiles.

The U.S. Navy’s layered defense is robust but limited by magazine depth and reload constraints, making it vulnerable to mass-fire tactics. The future survivability of CSGs will depend on distributed maritime operations, long-range carrier aviation supported by platforms such as the MQ-25 refueling drone, and rapid deployment of directed-energy weapons and advanced interceptors.

China also possesses the advantage in numbers. While U.S. missile interceptors are some of the most advanced in the world, they come at a high cost. Not only are they more expensive to produce in large numbers, but the U.S. manufactures fewer interceptors than China does anti-ship missiles, according to estimates.

(Feb. 13, 2013) A Standard Missile-3 (SM-3) Block 1A interceptor is launched from the guided-missile cruiser USS Lake Erie (CG 70) during a Missile Defense Agency and U.S. Navy test in the Pacific Ocean. The SM-3 Block 1A successfully intercepted a target missile that had been launched from the Pacific Missile Range Facility, Barking Sands, Kauai, Hawaii. (U.S. Navy photo/Released)

This is a significant threat to the U.S. and will likely be a considerable issue for the Navy in the event of a protracted conflict in the Pacific.

About the Author: Isaac Seitz

Isaac Seitz, a Defense Columnist, graduated from Patrick Henry College’s Strategic Intelligence and National Security program. He has also studied Russian at Middlebury Language Schools and has worked as an intelligence Analyst in the private sector.

More Military

The U.S. Military Purchased 2 Russian-Made Mach 2.35 Su-27 Flanker Fighters

The B-2 Spirit Stealth Bomber Has a Message for the U.S. Air Force