Key Points and Summary – The recent launch of Russia’s new hypersonic-armed submarine, Perm, serves as a stark reminder of the 2000 Kursk disaster.

-The Kursk sank with all 118 hands after a faulty torpedo caused a catastrophic secondary explosion.

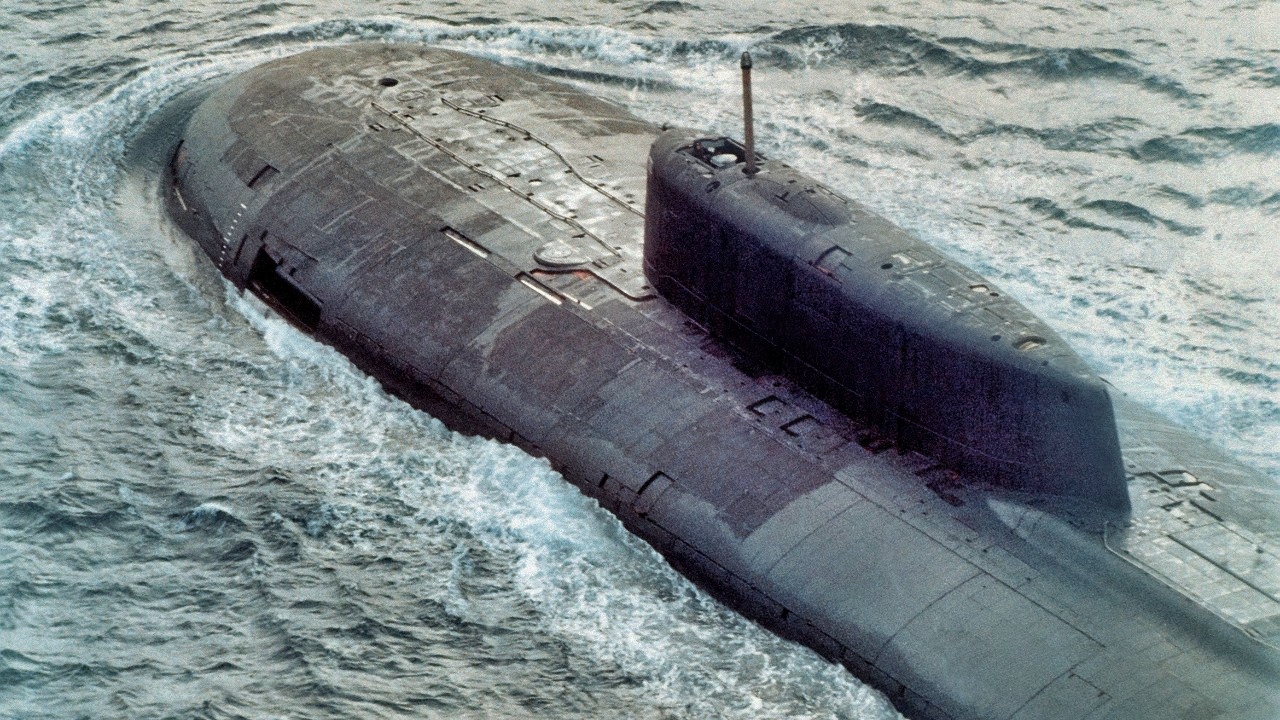

An elevated port side view of the forward section of a Soviet Oscar Class nuclear-powered attack submarine. (Soviet Military Power, 1986) Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-An investigation revealed the tragedy was a result of both technical failure—using unstable torpedo fuel—and institutional failure.

-A culture of secrecy and poor safety protocols led to a fatally delayed and mishandled rescue. As Russia launches ever-more-complex submarines, the Kursk remains a powerful cautionary tale about the deadly consequences of a dysfunctional naval culture.

A Torpedo Nightmare: How the Russian Nuclear Submarine Kursk

On March 27, 2025, Russian President Vladimir Putin presided over the ceremonial launch of Perm, a new nuclear-powered attack submarine, via video link from Murmansk.

Perm is the sixth vessel in the Yasen class and is the first to be designed from the outset to carry hypersonic Zircon cruise missiles as part of its standard armament.

The weapons it carries are a key part of Russia’s modern naval deterrent, with a reported range of roughly 900 km.

The missiles are also designed to penetrate advanced defenses—a characteristic of new submarine armament that contributes to discussions about the growing vulnerability of aircraft carriers.

But while Perm’s launch made headlines as evidence of Russia’s commitment to dominating the oceans, its arrival also reopens questions about safety, accountability, and submarine technology itself.

Oscar-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The Kursk disaster of 2000 demonstrates that even cutting-edge systems can fail, and institutional failures can exacerbate those failures.

The Kursk Submarine Disaster

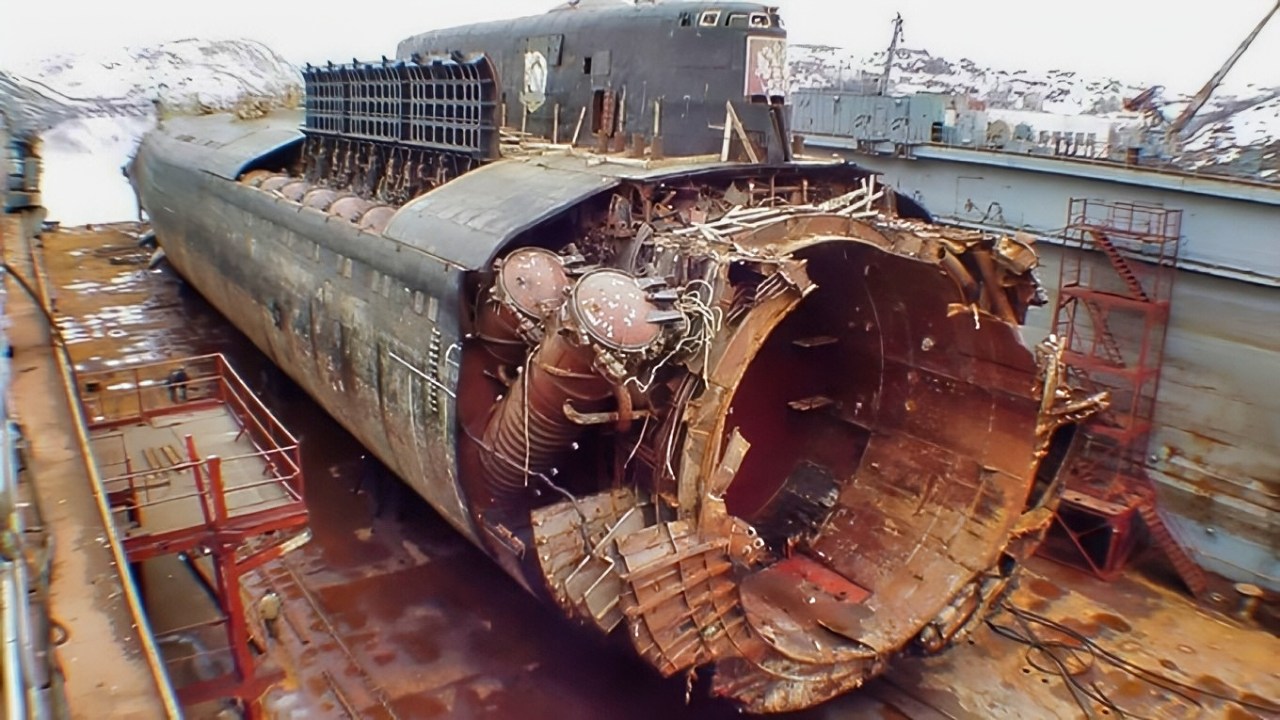

On 12 August 2000, the nuclear-powered K-141 Kursk submarine was participating in a naval exercise in the Barents Sea when a small explosion in a torpedo room triggered a much larger secondary blast, tearing the bow of the submarine apart.

Seismographs across northern Europe recorded the shockwaves and helped analysts to conclude that it was an internal explosion, rather than a collision, that destroyed the vessel.

The submarine sank to the sea floor, which some estimates say was as deep as 350 meters. It quickly became clear that any survivors of the blast would be lost to the sinking.

Rescue efforts were initiated, but they were delayed and mishandled.

Russia initially refused or delayed access to those attempting to help.

Between bureaucratic delays and old rescue gear, every person on the submarine ultimately died either as a result of carbon monoxide poisoning or asphyxiation.

Eventually, the wreck was salvaged – but 118 lives were lost.

The failure of command and oversight has long lingered, harming Russia’s naval credibility—and for good reason. The sinking occurred due to technical, institutional, and cultural failures.

The accepted cause, today, is a faulty torpedo that used high-test peroxide (HTP) as an oxidizer.

A leak in the torpedo is believed to have triggered a small explosion, which in turn set off a chain reaction of additional blasts. HTP is notoriously unstable under specific temperature or handling conditions, making it a dangerous choice for a torpedo.

Once the secondary explosion occurred, the forward compartments of the submarine – the sections at the front of the vessel that contain the control room and torpedo stores – were destroyed.

The magnitude of the blast was so large that it overwhelmed the design tolerances of the hull. Reports and investigations that took place in the wake of the explosion revealed poor maintenance, lax safety protocols, and degraded infrastructure – endemic in post-Soviet Russia’s navy – all contributed to the blast.

And, the culture of secrecy and hierarchy within the Russian navy is said to have permitted the delays in decision-making and prevented international help, resulting in the deaths of all crew members. That refusal, or at least the slow acceptance, contributed to the death toll.

Several other theories have been suggested over the years. Some says, a stray missile or a NATO submarine may have contributed to the crash, but these theories lack substantial evidence.

What we do know, though, is that the Kursk was a failure of both hardware and poor management, as well as an unproductive and dangerous culture within Russia’s navy.

Adapting for the Future

The launch of Perm in 2025 is not directly linked to the events of 2000, but it is part of an ongoing strategy to strengthen the country’s already substantial submarine fleet. Some estimates place Russia’s current fleet at 64 vessels, including 16 nuclear ballistic missile subs (SSBNs).

Sheer numbers, however, won’t insulate Russia from risk – and each new class of submarine is more complex than the last. Between propulsion, reactor safety, weapons integration, modern stealth systems and controls, each new generation of submarine in theory has more that can go wrong. And with more to go wrong, the Russian Navy has a thinner margin for error.

However, Russia’s submarine force is said to remain operating under strict secrecy with centralized control, meaning that technical problems—and failures—can still become significant liabilities.

Kursk demonstrated how a lack of transparency and poor organization can risk lives – and presumably, Russia is aware of this. Kursk is a cautionary tale for Russia, yes, but also for other major naval forces.

With the advent of submarines armed with hypersonic missiles, such as the Perm, the stakes are higher than ever.

A failure at sea could have catastrophic and cascading consequences, ranging from diplomatic fallout to escalation and even environmental chaos.

For the U.S. and allies, tracking and monitoring submarine developments like this matters for many reasons – not just because a large Russian submarine fleet poses a risk to American assets all over the world, but because disasters like the Kursk sinking in 2000 can happen all over again.

About the Author:

Jack Buckby is a British author, counter-extremism researcher, and journalist based in New York. Reporting on the U.K., Europe, and the U.S., he works to analyze and understand left-wing and right-wing radicalization, and reports on Western governments’ approaches to the pressing issues of today. His books and research papers explore these themes and propose pragmatic solutions to our increasingly polarized society. His latest book is The Truth Teller: RFK Jr. and the Case for a Post-Partisan Presidency.

More Military

‘Captain, We Have Been Hit’: A Tiny Nuclear Submarine ‘Sank’ $4.5 Billion Navy Aircraft Carrier

America’s F-35 Stealth Fighter Simply Summed Up In Just 1 Word

China’s New J-35 Stealth Fighter Simply Summed Up In Just 1 Word

The U.S. Navy Is Now ‘Cannibalizing’ Its Own Fighter Jets and Submarines

Operation Black Buck: How Avro Vulcan Bombers Broke Range Records in the Falklands War