Key Points and Summary – The F-47, the crewed centerpiece of America’s NGAD program, is being built to control packs of Collaborative Combat Aircraft, forcing the Air Force to rethink how many fighters it actually needs.

-In theory, a single F-47 with several loyal wingman drones could deliver the combat mass once provided by an entire squadron.

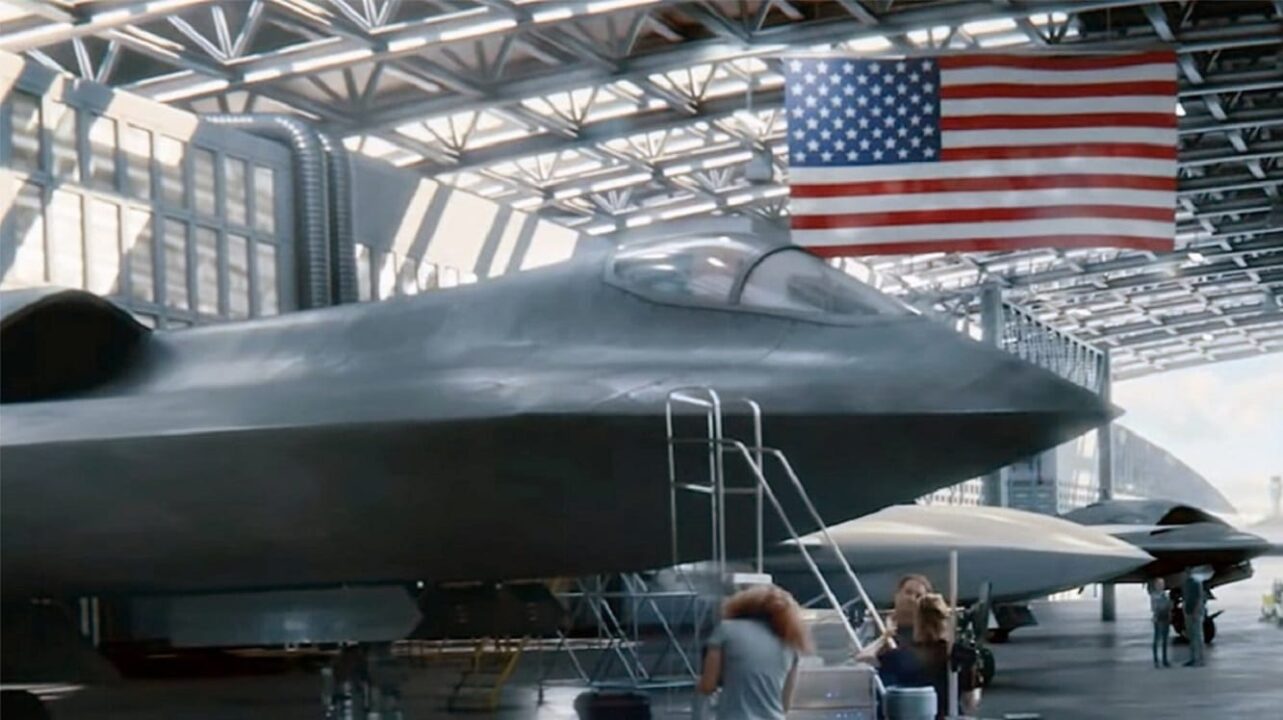

Boeing NGAD F/A-XX Fighter Rendering. Image Credit: Boeing.

-But that logic only holds if the U.S. can field and replace CCAs at scale—something its drone industrial base can’t yet guarantee.

-With China and Russia rapidly expanding both manned and unmanned fleets, a 150–200-jet F-47 force looks less like excess and more like strategic insurance.

Does the F-47 Need Numbers If It’s Built To Control Drones?

The US Air Force’s Next Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) program is built around more than just a new aircraft—it’s an entirely new system that combines a manned component and unmanned drone systems.

The manned component is the traditional fighter jet, widely expected to be designated F-47, which will act as a “quarterback” for autonomous drones.

This new human-machine teaming, which will use what’s known as Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCAs), has prompted the Air Force to reconsider how many new aircraft it really needs.

The US Air Force hasn’t explicitly stated that it has reconsidered the number of F-47s it plans to acquire because of it.

F-47 NGAD Artist Impression. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

After all, the program was envisioned from the beginning to include an unmanned element. But that said, their existence will unquestionably have changed Air Force planners’ calculations of how many fighters are truly necessary.

Former Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, for example, suggested in 2023 that there could be as many as five CCAs per manned flight in the NGAD program.

That’s game-changing. It’s hard to envision a scenario in which one aircraft equals the power of six that wouldn’t change how the US military, the Department of Defense, and the White House view procurement.

But that said, it’s not the only factor driving the decision; many factors will ultimately determine how many next-gen fighters the US needs, ranging from the threat environment to the actions of adversaries like China.

NGAD Was Designed to Make Numbers Matter Less

From the get-go, NGAD was described as a family of systems rather than a single aircraft, built around a manned fighter paired with multiple autonomous CCAs.

That functionality has been repeatedly described as turning the NGAD fighter into a “quarterback” for drones, with the drones handling scouting, electronic attack, weapons delivery, and high-risk penetrations into contested airspace. In contrast, the manned fighter and pilot remain in control.

That concept will inevitably shape the expected fleet size. Secretary Kendall has publicly stated that the cost of the NGAD program could limit procurement of the F-47, despite himself and other officials also acknowledging that a fleet of 200 or more might be necessary.

Ultimately, the CCAs are intended to provide the mass.

The Air Force’s acquisition target is remarkable in this sense, with at least 1,000 CCAs expected in the first tranche.

NGAD Artist Photo. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Planning documents and budget statements suggest a crewed NGAD fleet in the range of 150-200 aircraft, and the logic here is simple: if every F-47 controls two to five drones, the mass comes from the 1,000-strong CCAs.

But, this only works if the drones exist in large numbers, survive combat, and can be replaced faster than they are lost. And that’s where other factors come into play, too. Numbers, ultimately, still matter.

But Numbers Still Matter – And Probably Will For Years

The honest truth is that the United States does not currently have the drone industrial base needed to produce CCAs in enormous quantities.

Autonomy, teaming, and survivability are all improving, and the development of new-generation drone systems continues, and the U.S. is still producing unmanned systems in limited batches.

The industrial base’s limitations are no secret, and even the Air Force’s own modernization plans describe CCAs as a risk-reduction effort while autonomy and manufacturing scale up.

Referring to recent drone flight demonstrations, Air Force Secretary Troy Meink said that the flights “are giving us the hard data we need to shape requirements, reduce risk, and ensure the CCA program delivers combat capability on a pace and scale that keeps us ahead of the threat.”

But while America prepares for the long term, other countries are developing drone technology much faster.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has had the unintended consequence of dramatically scaling up its drone sector, powered in part by imported Iranian Shahed technology and later the construction of domestic assembly lines that now produce thousands of loitering munitions.

Russia has proven just how quickly a nation can scale low-cost UAV production under pressure. Western intelligence reporting has confirmed that Russia is now capable of producing Shahed-derived drones in large volumes at its Alabuga facility. In 2025, reports suggested that more than 5,700 Shahed drones were manufactured between January and September 2024.

The U.S. ultimately maintains a major quality advantage here. Still, quantity matters in attrition-heavy drone warfare – and Russia is demonstrating that it has an industrial model that the U.S. has yet to replicate.

China is moving even faster, too. Its GJ-11 stealth UCAV, FH-97A loyal-wingman concept, and rapidly expanding UAV families mean Beijing has an impressively diverse range of unmanned assets.

MD-19 Drone from China Screenshot from Chinese Social Media.

And perhaps more importantly, China is accelerating the production of its manned fighters at the same time, with J-20 production now steady and increasing.

In that context, the emerging consensus that 200 crewed NGADs should be the minimum is more about insurance than anything. Until the CCA fleet is proven, scalable, and replaceable at a rapid speed, it may be the number of drones tied to each NGAD—and not the NGAD count itself – that will matter most, at least in the near term.

About the Author:

Jack Buckby is a British author, counter-extremism researcher, and journalist based in New York who writes frequently for National Security Journal. Reporting on the U.K., Europe, and the U.S., he analyzes and understands left-wing and right-wing radicalization and reports on Western governments’ approaches to the pressing issues of today. His books and research papers explore these themes and propose pragmatic solutions to our increasingly polarized society. His latest book is The Truth Teller: RFK Jr. and the Case for a Post-Partisan Presidency.