Key Points and Summary – Boeing’s X-32 lost the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) contract to Lockheed’s X-35 (the future F-35) due to “fatal design compromises” driven by an overemphasis on “affordability.”

-While innovative, the X-32’s design had key weaknesses: its “gaping” chin-mounted air intake “impeded stealth” by exposing the engine to radar.

Boeing F-32 or X-32 Fighter Artist Rendition: Image Creator: Adam Burch/hangar-b.com.

Boeing X-32 Fighter Artist Drawing U.S. Air Force.

-Its large delta wing was poor for dogfighting.

-Most critically, its simplified STOVL (vertical landing) system, which used vectored-thrust instead of a separate lift fan, was “inferior” to the X-35’s, recirculated hot air, and caused “thermal stress,” leading to its 2001 defeat.

BONUS – We have included photos from our visits to the X-32, one in Ohio and another in Maryland. One, sadly, based in Maryland, is in bad condition, left to rot outside for years.

Is This Why the Boeing X-32 Failed?

The U.S. Department of Defense’s Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program of the late 1990s was a paradigm shift in tactical aviation.

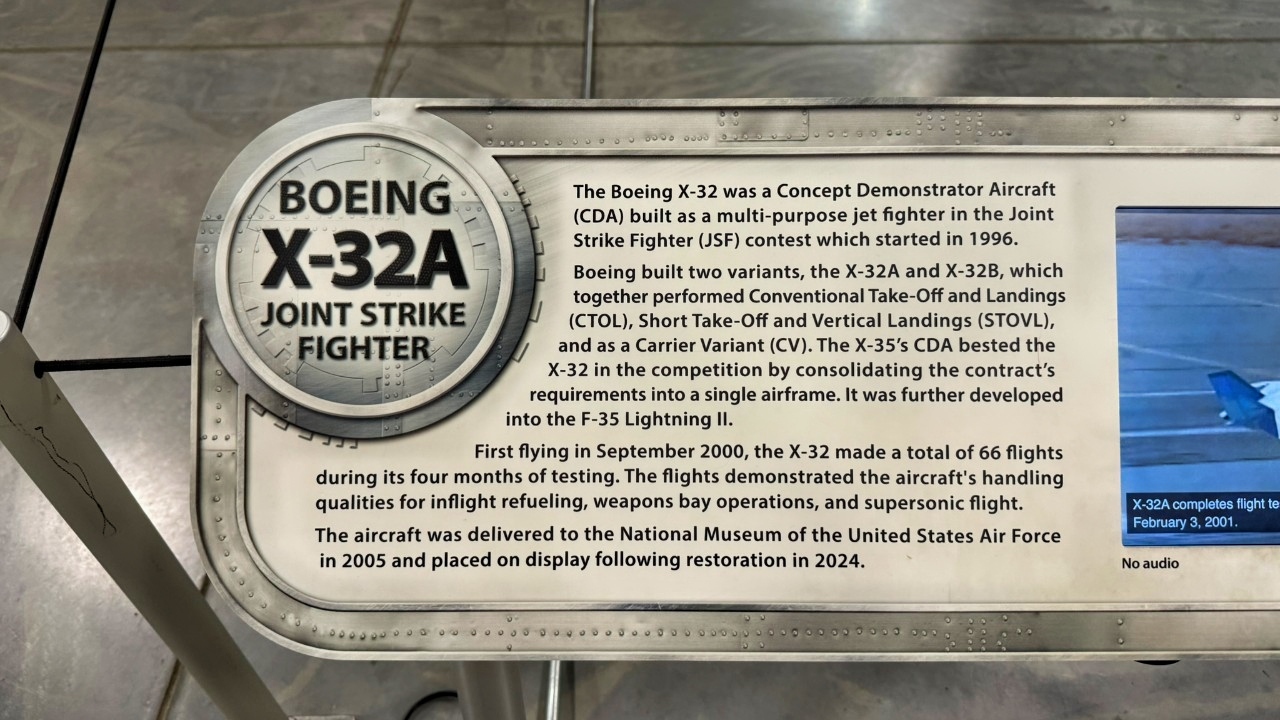

The aim was to develop a single stealth-capable fighter airframe that would serve the Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps. It was also intended to include variants for conventional take-off/landing (CTOL), carrier (CV), and short-take-off/vertical-landing (STOVL).

Prototypes were submitted for the ambitious project by both Boeing and Lockheed Martin. Boeing presented the X-32, and Lockheed presented the X-35.

Boeing’s entry ultimately failed to win over planners, offering a bold, truly innovative design that was perhaps, in some ways, ahead of its time—and flawed in its execution.

A series of design trade-offs and performance issues ultimately led to its defeat, but the design was remarkable and remains an essential piece of military and aviation history.

The JSF Race

Initiated in the 1990s, the JSF program sought to replace or supplement several aging aircraft types, including the F-16, A-10, and AV-8B, for the U.S. military and allied forces.

The idea was to create a new, common platform to reduce logistical burdens and costs.

In 1996, Boeing and Lockheed were selected to build “Conceptual Demonstration Aircraft” (CDAs), and the X-32 and X-35 were born.

By October 2001, the Department of Defense ultimately selected the Lockheed X-35 design for the contract. And because it was a winner-take-all contract, Boeing’s X-32 design fell by the wayside.

What the X-32 Got Right

Before diving into the technical merits of the X-32, it’s worth recalling what the Boeing X-32 actually was.

This was an advanced, single-seat, stealthy, multirole jet prototype intended to serve all arms of the U.S. military. Its distinctive appearance, dominated by a broad delta wing, an oversized chin inlet beneath the nose, and a gaping “smike-like” intake, all made it an instantly recognizable and even polarizing proposed platform.

The design emphasized simplicity where it could, as well as cost-effectiveness, rather than elegance. The delta wing was made of carbon fiber and offered internal fuel and structural advantages, while its chin inlet was intended to feed the engine with air more efficiently regardless of flight altitude.

Boeing’s engineers built the aircraft around three guiding principles: commonality, manufacturability, and affordability.

The company sought to minimize variation across CTOL, CV, and STOVL variants to reduce production costs and logistical/maintenance demands dramatically.

The designers also sought to use as few parts as possible across models to make the jet easier to build and maintain. And that was a clear winning strategy—even if the design itself wasn’t chosen.

The aircraft’s performance during testing proved credible, too. Its first flight took place on September 18, 2000, with 66 sorties completed over four months.

The jet proved itself, and the demonstrator worked as intended. So, the X-32 got a lot right. It was a serious engineering effort, and arguably more realistic in terms of production feasibility—and even more cost-conscious—than some earlier advanced fighter prototypes.

Design Compromises and Weaknesses

While the X-32 was certainly competent in many ways, there were several design compromises and weaknesses that ultimately led to its demise.

First is the delta wing, which did provide excellent internal fuel volume and structural stiffness at high speeds, but it let the aircraft down in terms of maneuverability.

A delta wing typically has a large wing area, which can increase drag and worsen maneuverability in sub-supersonic combat. The X-32’s wing sweep was roughly 55 degrees and spanned 9.15 m on the demonstrator, which meant it wasn’t an ideal dog-fighting machine.

The chin-mounted air intake, below the cockpit, also forced some compromises. While it supplied the engine with superior airflow, particularly the STOVL variant, where ram-air pressure is low or zero, the geometry exposed the engine in some ways.

Specifically, it meant that the engine was exposed to radar detection, increasing the aircraft’s radar signature and impeding stealth.

And as for the STOVL version, Boeing opted for a vectored-thrust system, meaning that the main engine redirected thrust through vectoring nozzles rather than adding a separate lift fan.

Costs primarily drove that simplified configuration, but it meant that the exhaust recirculated hot air and reduced thrust. It also put thermal stress on the aircraft during hover and transition. By contrast, the Lockheed X-35 design used a fan-shaft-driven lift fan and a swivelling central exhaust, creating superior STOVL performance – though at the cost of complexity. In this sense, the X-32 streamlined its design too much.

And then there were the matters of adaptability and future growth/change. Because Boeing strongly prioritized simplicity and cost, its demonstrator diverged more from the proposed production design than Lockheed’s did. That was enough for the Department of Defense to assess that the demonstrator’s performance may not translate into the production aircraft.

In the end, the Boeing X-32 failed because it simplified too much—not because it lacked innovation.

The X-32: Where You Can See Her Today in Maryland and Ohio (Our Photos)

Sideview of Boeing X-32B In Maryland.

Boeing X-32 Stealth Fighter in Maryland. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

Boeing X-32 NSJ Original Image. Credit: Christian D. Orr.

Boeing X-32 in Maryland NSJ Image September 2025. Image by Christian D. Orr.

Head On Boeing X-32 Fighter. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

Boeing X-32 Bright Image 2025. Credit: National Security Journal.

Boeing X-32 Fighter USAF Museum Dayton Ohio. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

Boeing X-32 Fighter at USAF Museum July 2025. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

About the Author:

Jack Buckby is a British author, counter-extremism researcher, and journalist based in New York. Reporting on the U.K., Europe, and the U.S., he works to analyze and understand left-wing and right-wing radicalization, and reports on Western governments’ approaches to the pressing issues of today. His books and research papers explore these themes and propose pragmatic solutions to our increasingly polarized society. His latest book is The Truth Teller: RFK Jr. and the Case for a Post-Partisan Presidency.

More Military

A ‘Small War’ Against Venezuela Is a Really Big Mistake

The Air Force’s Mach 2 F-15C/D Fighter Isn’t Going Anywhere

The United Kingdom Has a Message for the F-35 Stealth Fighter