Key Points and Summary – The F-16XL was a bold attempt to turn the nimble F-16 into a deep-strike workhorse.

-With its huge cranked-arrow delta wing, the XL carried more fuel, more weapons, and flew farther and more efficiently at supersonic speeds than a standard F-16, making it a prime candidate to replace the F-111 in the Enhanced Tactical Fighter competition.

F-16XL NASA Image

F-16XL Fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-Yet the U.S. Air Force chose the twin-engine F-15E instead, favoring survivability, payload, and a two-crew cockpit for complex strike missions.

-The XL never entered service but lived on as a NASA testbed—an engineering success that arrived before doctrine was ready for it.

F-16XL: The Radical Falcon That Lost to the Strike Eagle

The F-16XL was a radical variation of the well-known F-16 Fighting Falcon.

With a dramatically altered appearance, featuring a massive cranked-arrow delta wing, the F-16XL promised significant improvements in range, payload, and supersonic efficiency.

Yet despite strong performance, the XL never entered production, instead becoming an open question in what could have been.

Historical Context

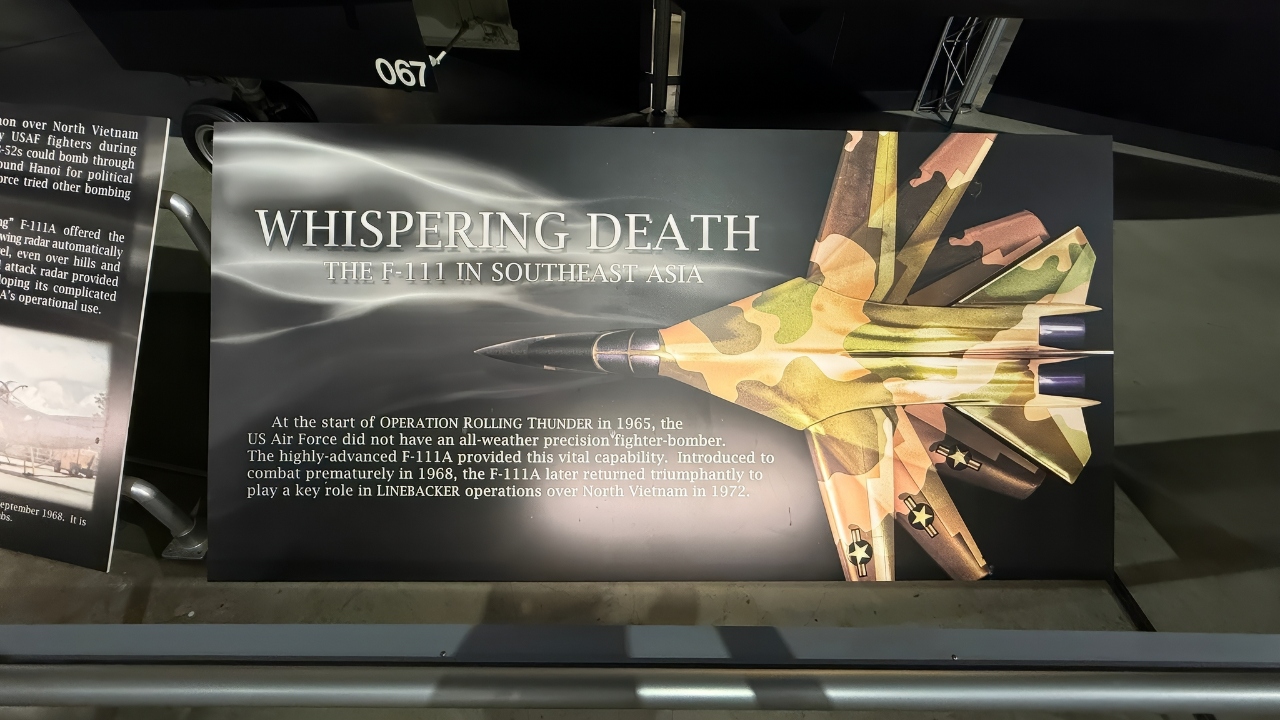

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the US Air Force sought a replacement for the F-111 Aardvark, a deep-strike platform that pioneered terrain-following radar and swept wings.

USAF Museum F-111 National Security Journal New Photo.

F-111 Photo from USAF Museum in Dayton. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

The replacement competition became the Enhanced Tactical Fighter (ETF) competition, pitting General Dynamics’ F-16XL against McDonnell Douglas’ F-15 Strike Eagle.

The XL was designed to build on the F-16’s famed agility while improving upon range, payload, and supersonic performance.

The F-15E, meanwhile, took a familiar airframe, unchanged, adding ground-strike capabilities.

The XL stemmed from the original F-16, but featured heavy modifications, optimized for long-range, high-payload strike missions.

Two prototypes were built, one single-seater and one two-seater.

Neither was intended to replace the standalone F-16, but to expand the F-16 family into a deep-strike role.

The differences between the original F-16 airframe and the XL were stark. The most obvious was the cranked-arrow delta wing, which increased wing area by 120 percent.

This allowed for much higher internal fuel capacity, increased payload stations (with up to 27 hardpoints), reduced drag at supersonic speeds, and, overall, better range and endurance without external fuel tanks—all performance metrics that facilitated deep-strike missions without dependence on tankers.

Indeed, the XL had a significantly greater combat radius than the standard F-16 and could carry heavier internal and external weapon loads without sacrificing as much performance.

F-16 Fighting Falcon Onboard USS Intrepid. Image Taken on September 18, 2025.

F-16 Fighting Falcon National Security Journal Photo. Taken on 9/18/2025 Onboard USS Intrepid.

Aerodynamically, the XL was optimized for supersonic cruise and dash, a departure from the original F-16, which was built with an aerodynamic focus on dogfighting performance. The XL retained good handling and improved upon high-altitude efficiency, but sacrificed some of the low-speed agility that the original F-16 was famous for.

The design was tailored to the USAF’s ETC demands—a strike aircraft that was cheaper than the F-111, less complex than a brand-new platform, and compatible with existing F-16 logistics and training pipelines.

The XL boasted lower development risk than a brand-new platform, high commonality with the existing F-16 fleet, and multirole flexibility that could replace the F-111.

Losing the Bid

The F-16XL lost the ETF competition; the USAF selected the F-15E, which is still in service today. The reasons behind the decision: the F-15E’s twin-engine configuration offered redundancy and better survivability over hostile territory (crucial for a deep-strike platform); the larger airframe was better suited for heavy, long-range strike missions; and the two-crew configuration was geared towards the complexity and cognitive demands of deep-strike operations.

But the XL was salvaged from defeat; the prototypes were never scrapped. Instead, NASA took ownership and used both extensively as research aircraft.

Over decades, NASA put the XL through the paces, testing supersonic aerodynamics, laminar flow, sonic boom reduction, and high-speed computational fluid dynamics validation. The tests provided NASA with valuable data for both military and civilian high-speed aircraft design.

Although the F-16XL never achieved its stated goal, the platform proved that large delta wings could deliver range and payload benefits without a massive airframe. Ultimately, the platform was an engineering success, a radical expansion of the F-16’s capabilities.

In hindsight, the F-16XL’s design looks modern, very much ahead of its time. The design priorities, emphasizing internal fuel volume, long-range capability, and reduced drag without external tanks, show some parallels with modern aircraft.

Take the F-35, also designed with an emphasis on internal fuel and range amid growing concern about tanker vulnerability in peer conflict. The F-16XL attempted to address range issues without anchoring aircraft dependence to a tanker; the need for such a platform has only grown more acute in modern A2/AD environments.

A U.S. Air Force F-35 Lightning II assigned to the 56th Fighter Wing, Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, performs a strafing run during Haboob Havoc 2024, April 24, 2024, at Barry M. Goldwater Range, Arizona. Haboob Havoc is an annual total force exercise that brings together multiple fighter squadrons from numerous bases to practice skills and test abilities in various mission sets. (U.S. Air Force photo by Staff Sgt. Noah D. Coger)

So, the aircraft failed in some respects because it was ahead of its doctrinal moment, not because the technology was incapable.

But as the F-16XL demonstrates, procurement outcomes aren’t driven solely by engineering merit.

The F-16XL was absolutely a capable aircraft, meeting or exceeding its performance goals, validating that large delta wings can work for strike efficiency.

But the platform’s ETF loss did show the USAF preference for redundancy and crew capacity, culminating in the F-15E’s selection, and the F-16XL’s relegation to relative obscurity.

About the Author: Harrison Kass

Harrison Kass is an attorney and journalist covering national security, technology, and politics. Previously, he was a political staffer and candidate, and a US Air Force pilot selectee. He holds a JD from the University of Oregon and a master’s in global journalism and international relations from NYU.