The U.S. Navy in 2025 Is in Decay: Key Points of This Article

-The USS Ohio’s delayed return to sea exposes a deeper crisis: America’s naval power is being choked by aging ships, overstretched shipyards, and unrealistic fleet plans.

(March 31, 2006) – The guided missile submarine USS Florida (SSGN 728) conducts sea trials off the coast of Virginia. Florida will be delivered to the Fleet in April, and a Return To Service ceremony is scheduled for May 25 in Mayport, Fla. As the second of four SSBN submarines to be converted to SSGN, this nuclear-powered submarine will have the capability to: launch up to 154 Tomahawk cruise missiles; conduct sustained special warfare operations with up to 102 Special Operations Forces (SOF) personnel for short durations or 66 SOF personnel for sustained operations; and provide approximately 70 percent operational availability forward deployed in support of combatant mission requirements. U.S. Navy photo by Chief Journalist (SW/AW) Dave Fliesen.

The guided missile submarine USS Florida (SSGN 728) arrives in Souda Bay, Greece, May 21, 2013, for a scheduled port visit. The Florida was underway in the U.S. 6th Fleet area of responsibility conducting maritime security operations and theater security cooperation efforts. (U.S. Navy photo by Paul Farley/Released)

-With only about 296 ships and rising maintenance backlogs, the Navy’s 30-year plan depends on industrial capacity that simply doesn’t exist.

Legacy cruisers and destroyers consume dry-dock space and money that should go to new hulls, even as China launches warships at record pace.

-Dr. Andrew Latham argues the Navy must deliberately retire obsolete ships, accelerate shipyard modernization, and scale its ambitions to what industry can actually build—or watch rivals seize the seas.

America’s Navy Is Hollowing Out: Why Aging Ships and Broken Yards Are the Real Threat

When the USS Ohio (SSGN-726) slid out of dry dock this spring after a three-year maintenance period, it was more than one submarine returning to sea. It was a wake-up call. The bedrock of American sea power is cracking from age, delay, and industrial atrophy.

China is pouring steel into warships at a rate that the United States can barely match, moving closer to numerical parity under the sea. America’s shipyards do not have the dry docks or the workers to sustain the fleet.

Suppose the Navy continues to cling to legacy hulls, defer the modernization of shipyards, and make promises it cannot keep. In that case, it will lose not only money and time but its strategic edge in the water.

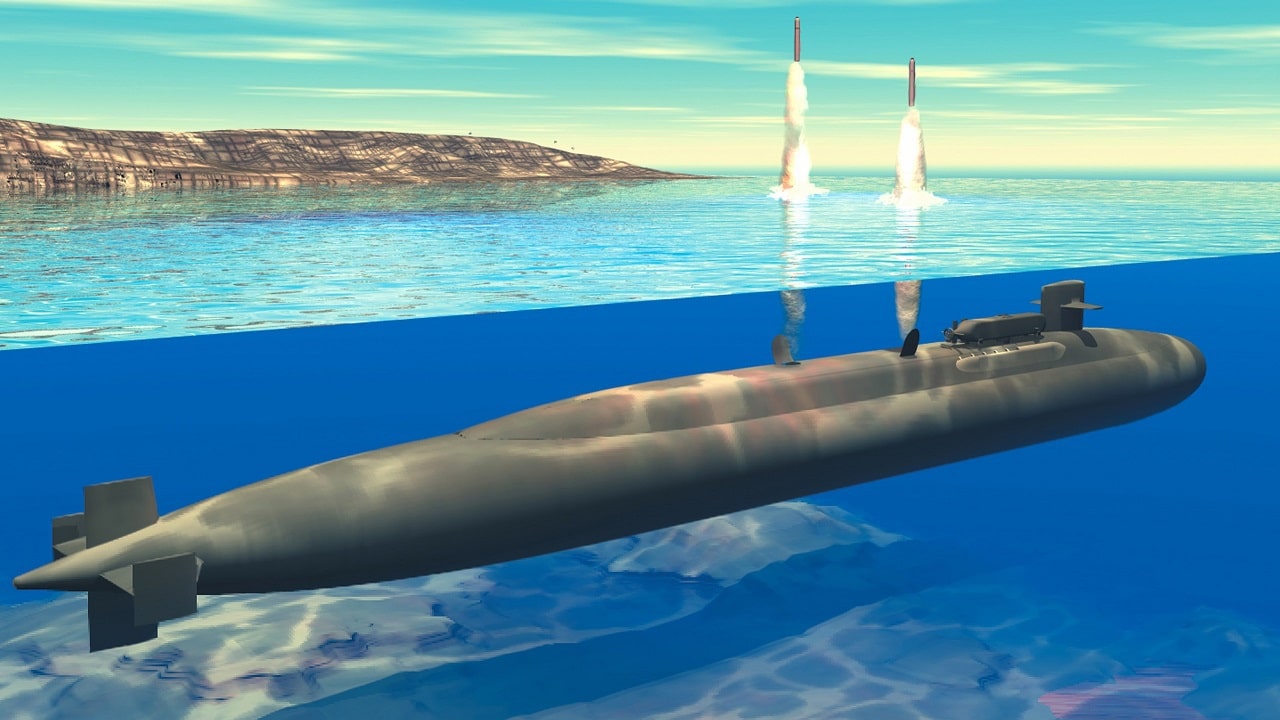

Ohio-class SSGN. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

An artist rendering of the future U.S. Navy Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines. The 12 submarines of the Columbia-class will replace the Ohio-class submarines which are reaching their maximum extended service life. It is planned that the construction of USS Columbia (SSBN-826) will begin in in fiscal year 2021, with delivery in fiscal year 2028, and being on patrol in 2031.

The Ohio’s tale is not merely an anecdote – it is a warning sign. The structural condition of the Navy is deteriorating as the fleet shrinks and maintenance costs rise. The “battle force” inventory of about 296 ships and submarines will decline through the late 2020s, even as competition on the sea intensifies.

The Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan calls for average annual construction spending of roughly $40 billion over the next decade—46 percent more than recent appropriations, according to the Congressional Budget Office. The chasm between the Navy’s aspirations and industry’s ability to deliver is expanding into a valley.

The Shipyard Challenge for the U.S. Navy

That valley will be measured not only in dollars but in capacity. Four shipyards build nearly all major hulls—two for submarines, two for surface combatants—and all are straining, with obsolete infrastructure and labor shortages. GAO audits have found long maintenance backlogs for attack submarines, and the Virginia-class production line still falls short of the goal of two hulls per year. As soon as the 2030s, Los Angeles-class attack boats will begin retiring, but not fast enough to reduce maintenance demands.

Surface shipbuilding faces similar constraints. Construction of Arleigh Burke destroyers has fallen short of targets, the new Constellation-class frigate program is behind schedule, and inflation and design complexity have driven up the price tag of every new hull.

The Navy’s long-range shipbuilding plan counts on the industry to right itself and deliver new hulls on time and on budget—an assumption for which there is no evidence.

Old Ships, Bigger Problems

This is the triad throttling U.S. sea power: aging ships fighting with new builds for maintenance resources, new hulls that arrive late and over budget, and shipyards that cannot expand fast enough to meet demand.

In that context, the reluctance to retire legacy hulls becomes a form of strategic self-deception. The Navy cannot rebuild the fleet by sustaining every ship it has today.

There are too many aging hulls taking manpower, dry-dock space, and maintenance dollars that should be fueling the modernization effort.

The first step must be to accept the need for deliberate divestment. Some ships are no longer worth sustaining. A cruiser that spends half its life in dry dock is a liability, not a deterrent. Retiring obsolete hulls will free money and manpower for new construction. The Navy has already accepted the fact that the fleet size will dip before it goes back up; now it must turn that realization into policy.

The second step is industrial renewal. Shipyards must be modernized, the skilled workforce stabilized, and supply chains reshored for critical components—propulsion systems, electronics, specialty metals.

As part of the Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program, full modernization of shipyards would not be achieved until 2046. That is far too late. Without a faster investment timeline, the facilities that maintain nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers will remain bottlenecks in both peace and war.

The third step is calibrating ambition to capacity. A 400-ship fleet or vast swarms of unmanned surface and undersea vehicles make for good speeches, but they are poor strategy. Ships in name only are worth little. Numbers mean little without readiness and sustainment. A smaller, younger, more reliable Navy, one that can deploy when ordered, is more strategically credible than a sprawling but brittle one propped up by deferred maintenance and wishful thinking.

The math is brutal. Consider, for example, a hypothetical program to keep fifty legacy destroyers afloat while ordering thirty new ones. If ten are delivered on schedule but the rest come years late, the result is fewer effective hulls, greater costs, and a readiness decline. This is not a thought exercise. This is a summary of the current data.

The geostrategic imperative has rarely been greater. China is building new destroyers, frigates and submarines at a pace that exceeds any other great power since the height of the Cold War, rapidly eroding its qualitative advantage against the United States.

Japan and South Korea are quietly expanding their advanced fleets, leveraging a hybrid approach of modular production and cutting-edge ship design. Russia, shackled by its fiscal limitations, is still building ships. New submarines are coming in quantity, and will project power across the Arctic and Pacific. The contest for naval supremacy, therefore, is a contest of industry – not of rhetoric, but of productive capacity. The winner in the 2030s will be the one that can produce the most.

What the Critics Will Say

Critics will argue that such industrial renewal is impossible because there is no political will to retire large numbers of ships. Risking geopolitical decline, they will say, invites aggression. To which one can only reply: Keeping every worn-out warship in the water is also a risk. An old fleet breaks more often, takes longer to react, and drains money from the modernization of the force. Quality, not quantity, is what deters. A smaller, modern, deployable Navy is a stronger signal than a bloated museum fleet kept afloat with tape and Band-Aids.

Industrial rejuvenation is not just bureaucratic housekeeping; it is strategy. Shipyards are as critical to deterrence as aircraft or missiles. An industrial base that cannot produce on time and at scale means that the most elegant strategic plans will be fantasies.

How to Save the U.S. Navy

Shipbuilding must be treated as national infrastructure, not as a procurement line item in a budget. A ship that cannot be built on time and on budget is not an asset; it is an illusion. For too long, American naval policy has been guided by nostalgia. Successive administrations have tried to preserve legacy fleets while promising game-changing ones just over the horizon. But the oceans are not sentimental.

They reward those who can sail, sustain, and fight. America’s competitors are accelerating; its own production lines are crawling. The longer that imbalance persists, the more severe the reckoning will be.

The wakeup call has already sounded. The fleet is aging, costs are spiking, and shipyards are falling behind. The Navy can still turn it around—but only if it makes hard choices about what to retire, invests in the shipyards that sustain its power, and calibrates ambition to capacity.

Otherwise, the United States will be left maintaining ships it can no longer use, waiting for ships it cannot build, and watching rivals take the seas it once ruled.

About the Author: Dr. Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. You can follow him on X: @aakatham. He writes a daily column for the National Security Journal.

Mark Forrest

October 24, 2025 at 8:49 pm

Fake Liberal news! I’m sick of all of you, constantly trashing the US Military, while telling us how great, powerful and ready the Chi-coms are!!!!! At least try to hide your bias towards America!!!

Grayfox41

October 25, 2025 at 11:55 am

Unfortunately, Obama’s DEI has not produced functional naval vessels. Hopefully, President Trump and SoW Hegseth can resurrect a real Navy fron the DEI debacle.