Key Points and Summary – The Ford-class aircraft carrier delivered real deck-cycle and electrical gains—but at the worst possible strategic moment.

-As China and Russia fielded massed anti-ship missiles, the Navy diverted years of money and leadership attention to debug a single, exquisite platform while the attack-submarine fleet shrank and maintenance backlogs ballooned.

Aviation Boatswain’s Mate (Equipment) 3rd Class Mark Ruiz, assigned to Air Department aboard the world’s largest aircraft carrier, USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78), prepares a Carrier Air Wing 8 F/A-18E Super Hornet attached to Strike Fighter Squadron 37 for launch on the flight deck, Aug. 1, 2025. Gerald R. Ford, a first-in-class aircraft carrier and deployed flagship of Carrier Strike Group Twelve, is on a scheduled deployment in the U.S. 6th Fleet area of operations to support the warfighting effectiveness, lethality and readiness of U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa, and defend U.S., Allied and partner interests in the region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Mariano Lopez)

The world’s largest aircraft carrier, USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN 78), conducts flight operations in the North Sea, Aug. 23, 2025. Gerald R. Ford, a first-in-class aircraft carrier and deployed flagship of Carrier Strike Group Twelve, is on a scheduled deployment in the U.S. 6th Fleet area of operations to support the warfighting effectiveness, lethality, and readiness of U.S. Naval Forces Europe-Africa, and defend U.S., Allied and partner interests in the region. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Maxwell Orlosky)

-Submarines are America’s asymmetric edge: they survive the sensor-missile revolution and hold adversary fleets and bases at risk.

-A smarter sequence would have front-loaded undersea capacity and fixed maintenance before sprinting on supercarriers.

-The way forward is clear: finish Fords already in train, maximize Virginia output and readiness, extend air-wing range, and invest in breaking the enemy’s kill chain.

The U.S. Navy’s Aircraft Carrier Choice Has Consequences

If you were building a fleet for the 1990s, the Ford-class aircraft carrier is a reasonable bet: bigger electrical margins, faster deck cycle times, and room to grow new sensors and weapons. If you were building a fleet for the 2020s—an era of Chinese anti-ship ballistic missiles, Russian hypersonic shots, and the mass proliferation of long-range cruise missiles—the calculus looks different.

The Navy poured tens of billions of dollars and years of schedule into the Ford class precisely as the ocean got deadlier for big decks and the attack-submarine shortfall became acute. The result is a lingering strategic ache: too much capital locked in a handful of exquisite ships, too few submarines to exploit America’s best asymmetric advantage, and a production base still struggling to deliver undersea hulls on time.

This is not a “carriers are obsolete” screed. It’s a hard look at opportunity cost. What we bought—and what we didn’t—across two crucial decades.

The Threat Picture Changed Faster Than The Fleet

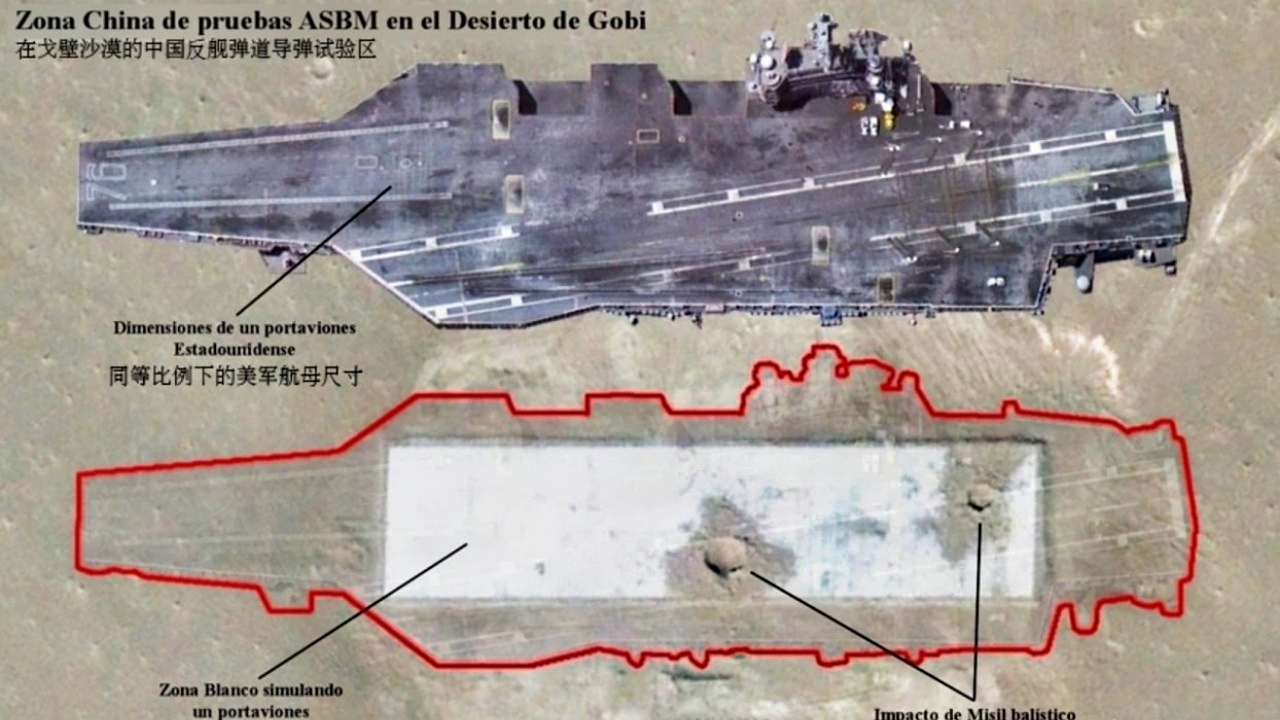

By the early 2000s, the warning lights were already blinking. China was fielding anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs) designed to hold carriers at risk at theater ranges and layering those with air- and sea-launched cruise missiles. Russia was modernizing its own missile families and experimenting with faster, more maneuverable weapons. Both competitors were building the kill chain that matters: the sensors, data links, and command loops to find, track, and service a moving naval target at long range.

DF-26 China Missile Attack on Fake Aircraft Carrier Cut Out. Image Credit: Chinese Weibo Screenshot.

At the same time, the cost to keep a single supercarrier at sea—escorts, air wing, logistics train—remained enormous, and the air wing’s practical striking radius without robust organic tanking had been trending shorter for years. The Navy’s answer on range is coming (and needed), but it arrives late: the MQ-25 tanker is only now moving toward fleet introduction, and long-range carrier weapons have lagged the threat curve.

In that context, submarines are the anti-fleet’s natural predator. They don’t advertise their position, shrug off most sensing architectures, and can hold the very ships and shore complexes that enable the missile threat at risk. If there was ever a moment to shift marginal dollars from visible mass to invisible leverage, it was the last twenty years.

The Bet On Ford: What We Bought On Purpose

The Ford class wasn’t conceived as a vanity project. It aimed to fix real problems in the Nimitz aircraft carrier template: steam catapults that guzzled manpower and maintenance, arresting gear that struggled with lighter aircraft, weapons flows that clogged deck choreography, and islands that stole precious square footage from the flight deck.

Electromagnetic launch and advanced arresting promised precise energy control across a wider aircraft envelope—vital as the air wing shifts to lighter unmanned aircraft and heavier strike loads. Advanced weapons elevators and a re-sited island aimed to keep the deck flowing. A beefier electrical backbone offered headroom for future sensors, defensive systems, and power-hungry mission kits. The ship’s designers wanted a faster, more sustainable airfield at sea with fewer sailors pulling levers in a steam-soaked bowelscape.

In peacetime exercises and the Ford’s first operational deployments, much of that logic has begun to show. Once systems are working, the deck rhythm is smoother. The sea trials and partial deployments proved that the concept can deliver. But none of that erases what it cost—in time and opportunity—to get here.

The Bill Came Due In Time, Money, And Focus

First-of-class ships always suffer teething problems. The Ford’s were prolonged and public. Integration issues with electromagnetic launch and recovery systems, stubborn weapons-elevator problems, and a long trail of reliability work pushed the first full deployments years to the right and fed budget growth that Congress and the press could not ignore. The Navy has made progress—but progress measured in years still carries a steep strategic price.

DF-17 Missile from China. Image Credit: PLA.

DF-17 Missile from China. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Every schedule slip on the carrier side wasn’t just a shipyard headache; it was a budgetary gravity well pulling dollars, attention, and political capital toward making one ship class whole. Meanwhile, the attack-submarine shortfall deepened, the undersea industrial base strained to keep pace with new Virginia-class construction and deferred maintenance, and submarine availabilities stretched into multiyear odysseys. A balanced fleet cannot be built if one pillar monopolizes the crane.

The Opportunity Cost: Too Few Submarines When We Needed Them Most

Nothing on—or above—the water holds at-range adversaries more honestly than a hunter-killer submarine. For two decades, the Navy’s own force-structure analysis has pointed to a requirement in the mid-60s for attack subs; inventories dipped into the 40s as older Los Angeles-class boats retired faster than Virginias arrived. Maintenance backlogs compounded the problem: a significant share of the fleet sat pier-side awaiting yard time, parts, or people.

The industrial base is trying to surge. But you cannot surge what you didn’t build—factories, dry docks, welders, and inspectors are not spares you swap off a shelf. Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarines, rightly the Navy’s top priority, take finite yard capacity and the most experienced hands. Attack boats then fight for what’s left. The result is an undersea force smaller than the mission set demands at the very moment an adversary navy is growing and learning to contest the open ocean.

Imagine a counterfactual: shave a carrier from the shipbuilding queue in the 2010s, redirect the procurement tail and some R&D headcount into the submarine industrial base, accelerate two-per-year Virginia buys with torpedo-tube and payload-module capacity, and pay down the maintenance bow wave. A decade later, the Navy might have half a dozen more deployable attack boats, tighter depot cycles, and shipyards better postured for the next-generation SSN. In the Indo-Pacific, that buy creates real strategic friction.

The Aircraft Carrier In The Crosshairs

It’s not that carriers are suddenly fragile glass cannons. A modern carrier strike group is a porcupine with a lot of quills: Aegis escorts, layered interceptors, electronic warfare, decoys, deception, and the ability to complicate an adversary’s targeting picture through emissions control and maneuver. But honesty demands we say the quiet part out loud: the missile salvos are getting bigger, faster, and smarter, and the ocean is getting more connected by sensors every year. The adversary’s kill chain won’t be perfect—but it doesn’t have to be if volume makes up the difference.

Norfolk, VA. (May 7, 2008)-The Virginia-class submarine USS North Carolina (SSN 777) pulls into Naval Station Norfolk’s Pier 3 following a brief underway period. North Carolina was commissioned in Wilmington, N.C. on May 3, 2008. (U.S. Navy Photo By Mass Communications Specialist 3rd Class Kelvin Edwards) (RELEASED)

Virginia-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The right response is to dilute the target: distribute lethality across more nodes, force longer kill chains with more failure points, and keep the enemy guessing where the next strike is coming from. Submarines do that by default. Carriers can contribute to distribution with longer-legged air wings, unmanned adjuncts, and stand-in weapons—but they are still big, knowable targets when the balloon goes up.

“But Carriers Deter, And We Need Deterrence”

Absolutely. An aircraft carrier parked in contested water is politics by other means. It reassures allies and deters opportunists, often without a shot fired. But deterrence has flavors. In an era when the adversary’s confidence rests on land-based missiles and coastal anti-ship complexes, the quiet threat of an attack boat off your choke point or within missile reach of your naval base may bite harder than the visible threat of a big deck beyond the horizon.

Deterrence also relies on perceived staying power. A carrier presence that can only be sustained by heroic maintenance sprints, and a submarine force that cannot generate enough deployable hulls, undercuts the message. Volume—and the ability to keep it forward—counts as much as the logo on the flight deck.

What We Should Have Bought More Of

The case for more submarines is not a bumper sticker. It is a concrete shopping list we could have advanced faster:

Virginia-Class Attack Boats With Payload Margin. Torpedo-room capacity and Virginia Payload Modules matter; they let an SSN carry a mixed bag of heavyweight torpedoes, cruise missiles, and specialized payloads for seabed warfare and ISR.

Industrial Base Muscle. The people, tooling, and dry-dock upgrades that turn two boats per year from aspiration into routine. That money pays off for Columbia, for Virginia, and for SSN(X).

Maintenance Capacity And Parts Pipelines. Submarine readiness has been strangled less by doctrine than by backlogs. Fixing availabilities is as much a deterrent as a new hull.

Kill Chain Killers. Undersea payloads and tactics to blind or confuse the adversary’s maritime targeting network. A submarine that kills the sensor web often does more for the carrier than a cruiser stacked with interceptors.

That list is not cheap—but neither is a supercarrier. And unlike a single exquisite hull, these investments compound across the force.

The Ford Class Still Brings Real Strengths—But They Are Niche Without Numbers

Give the Ford its due: once debugged, electromagnetic launch and arresting expand the air wing’s envelope; advanced weapons elevators speed deck cycles; the electric plant gives headroom for directed-energy defenses and power-hungry sensors; the island shift opens valuable deck real estate. In a low-intensity environment, a Ford-class ship is an airpower machine with a smaller crew and a cleaner maintenance bill of materials than a steam-era boat.

Even against a peer, carriers remain central for airborne early warning, electronic attack, sea control, and crisis response where basing is contested or denied. The coming MQ-25 tanker and longer-range weapons restore precious miles to the air wing’s radius. A future F/A-XX adds reach and survivability that the current jets can’t match. In short, carriers still matter. They just no longer monopolize the fleet’s marginal dollar.

The Simple Strategic Error: Sequencing

The Navy’s mistake wasn’t building Ford. It was building Ford first—consuming scarce schedule, money, and leadership mindshare—when the immediate strategic return on investment was underwater. If the Navy had front-loaded submarine capacity, maintenance throughput, and the munitions pipeline in the 2000s and early 2010s, the 2020s Ford would feel like icing, not the cake.

Sequencing matters because complex programs don’t just compete for authorizations; they compete for executive attention. Every hour a three-star spends wrestling elevator integration and launch-system reliability is an hour not spent beating suppliers and shipyards into a sustainable rhythm on attack boats. You get more of what you work, not what you brief.

What A Better Balance Looks Like Now

We can’t rewind the last twenty years. But we can make the next ten smarter.

Throttle The Carrier Buy To A Sustainable Pace. Finish the hulls already committed, drive reliability into EMALS/AAG/weapon-elevator production, and avoid new carrier starts until the undersea backlog and maintenance capacity recover.

Maximize Undersea Output. Fund two-per-year Virginias for real, with the industrial base investments that make the pledge credible. Protect Columbia’s schedule while expanding the talent pool and tooling that benefit both programs.

Fix Maintenance Before You Promise More Ships. Readiness gains from cutting availabilities by months will outperform the next procurement announcement in a fight that could start next year, not in 2035.

Accelerate The Air Wing’s Reach. Field MQ-25 to every air wing that can take it, move longer-range anti-ship and land-attack weapons into the magazines, and design F/A-XX around range and survivability first.

Invest In Kill-Chain Breakers. Spend aggressively on the deception, jamming, cyber, and space tools that make long-range missile targeting hard. Every broken link in the adversary chain buys your big decks time and your subs freedom.

Hedge With Distribution. Don’t put all the Navy’s lethality into a handful of exquisite platforms; spread it across more shooters—submarines, surface combatants, maritime patrol aircraft, and unmanned systems—to complicate the enemy’s math.

These are not either-or choices forever. They are sequencing choices for the 2020s so the Navy arrives in the 2030s with a force that can fight while it modernizes, not modernize while hoping it doesn’t have to fight.

The Political Economy We Ignored

Aircraft carriers are not just ships; they are coalitions of districts. They concentrate jobs, command prestige, and visible symbolism in a way that submarines—quiet by design—do not. That political gravity helped keep the carrier line humming even when the threat suggested a shift. It is understandable; it is also how great powers drift into misallocation.

Submarines have a different political problem: their value is invisible until a crisis, and their production is distributed among suppliers whose names don’t fit on a flight deck. Fixing that asymmetry requires leadership: make undersea capacity the visible national project it deserves to be and fund it like we mean it.

The Bottom Line on the Aircraft Carrier

The Ford-class aircraft carrier is a remarkable ship. It is also the wrong place to have tied up so much time, money, and senior-leader attention while a missile revolution spread and the submarine fleet shrank. Carriers still matter for presence, air control, and crisis response. They will matter more when the air wing’s range and survivability improve. But the decisive marginal investment in the missile age is underwater: more attack boats, better maintenance, thicker munitions and parts pipelines, and the kill-chain warfare that makes an adversary’s salvos fail more often than they hit.

The mistake isn’t existential; it’s prioritization. We can fix that—if we choose to buy the fleet the fight demands, not the one our nostalgia celebrates.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Miliary

The U.S. Navy’s Constellation-Class Crisis Boiled Down to 4 Words

The F-20 Tigershark Light Fighter Boiled Down to 4 Words

China Claims New J-35 Stealth Fighter Is ‘Invisible’

The 5 Greatest U.S. Navy Aircraft Carriers Of All Time

The Navy’s New Ford-Class Aircraft Carriers Can’t Hide All The Problems Anymore