How is the U.S. Army Fixing Its Recruiting crisis?

In the years following the drawdown of the Wars on Terror, the US military found itself with a problem.

British Royal Air Force Regiment troop cycles M500 Shotgun at the Winston P. Wilson (WPW) and 27th Armed Forces Skill at Arms Meet (AFSAM) at Robinson Maneuver Training Center, Ark, 2018. The annual events, hosted by the National Guard Marksmanship Training Center (NGMTC), offer Servicemembers from the National Guard and international community an opportunity to test marksmanship skills in a battle-focused environment.

Recruiting and retention lagged behind the Army’s goals, hindering its ability to maintain a cohesive force.

While disinterest on the part of young people was a problem, a bigger issue was that the physical, legal, and intellectual standards used for a recruiting baseline excluded some three-quarters of eligible young Americans.

This left the Department of Defense with a quandary: adjust standards, or change operations to match the reduced flow of recruits.

This was not the first time the military had faced such a problem, but previous instances had occurred under vastly different political and economic circumstances.

While the jury remains out on an overall evaluation of the program, at this point, it appears to be a significant success compared to earlier projects, including Robert McNamara’s Vietnam-era “Project 100000.”

The New U.S. Army Recruiting

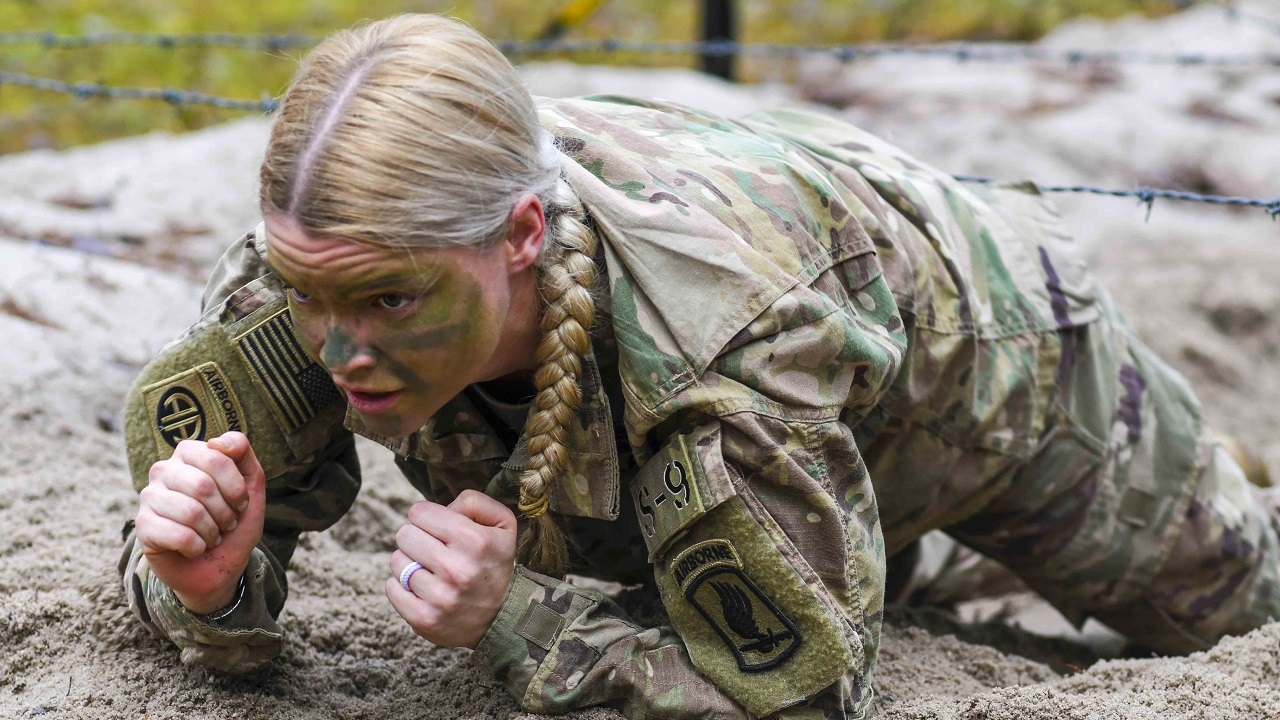

The Army designed the Future Soldier Preparatory Course (FSPC) to close two gaps. The first is between the number of soldiers the Army wants and the number it has been able to recruit in recent years.

The second gap was between the aspirations of men and women who wanted to join the Army and the basic physical, intellectual, and legal standards the Army requires of new recruits.

Based in Fort Jackson, South Carolina, the FSPC puts would-be recruits through what amounts to preparatory basic training, designed to generate physical fitness (usually measured in terms of weight, waistline, and basic exercise proficiencies) and improve test scores.

The pilot FSPC (launched in 2022) project achieved enormous success in improving recruit performance before basic training, as measured by both physical and intellectual metrics.

U.S. Army Staff Sgt. Alexander Trott, a paratrooper with 1st Squadron, 91st Cavalry Regiment, 173rd Airborne Brigade, fires his MK22 Advanced Sniper Rifle during sniper training at the 7th Army Training Command’s Grafenwoehr Training Area, Germany, June 7, 2024. A 1-91 CAV sniper team will participate at the International Danish Sniper Competition later this month. The 173rd Airborne Brigade is the U.S. Army’s Contingency Response Force in Europe, providing rapidly deployable forces to the United States European, African, and Central Command areas of responsibility. Forward deployed across Italy and Germany, the brigade routinely trains alongside NATO allies and partners to build partnerships and strengthen the alliance. (U.S. Army photo by Markus Rauchenberger)

Two expansions of the program since that point have seen similar success, resulting in an observable recruiting surge that President Trump and Secretary of Defense Hegseth have taken credit for. The program has been so successful that the Navy has adopted similar measures to manage its own recruiting shortfalls.

McNamara’s 100000

Because the Future Soldier Preparatory Course involves a creative approach to resolving the tension between high standards and the need to recruit more soldiers, some have compared it to Project 100000, a Vietnam-era program designed to expand Army recruitment to populations that previously had been excluded because of low academic or physical evaluations (in practice, opening up recruiting for candidates who scored in the 10th to 30th percentile on armed forces recruting tests).

Project 100000 was designed in a different time to solve a problem that was in some ways the same but in other ways much different.

The Project resulted from two impulses; the first a need to close the gap in recruitment created by US involvement in the Vietnam War, and second a belief in the power of technology to close gaps in testing and intellectual performance.

Essentially, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara believed that he could address the Vietnam manpower problem while simultaneously resolving the issue of low-scoring recruits by placing them in front of educational videotapes.

Project 100000 was also justified in terms of supporting Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty by giving poor Americans the opportunity to take advantage of military service to improve socio-economic outcomes for they and their families.

By nearly every account, Project 100000 failed. Although exact statistics are hard to come by, reports from Vietnam suggested that Project recruits suffered higher casualties and performed at lower levels of effectiveness than “normal” soldiers.

Testing was often fraudulent, with test centers coaching illiterate candidates through their paces. Post-war outcomes were also negative, with veterans of Project 100000 suffering from worse socio-economic outcomes than non-veterans from comparable groups.

In the end, Project 100000 has served to do little more than replace high-scoring potential recruits (many of whom enjoyed college deferments) with low-performing recruits, to the detriment of the latter and of the fighting capacity of the US armed forces.

The Differences

While the need that generated both programs and some of the logic that sustains them is the same, the differences are nevertheless profound.

Most of the problems addressed by the Future Soldier Preparatory Course involve physical fitness, and regularized intellectual testing since the 1960s has become much better at distinguishing between low scores and significant intellectual disability.

McNamara’s folly also came at a much earlier stage in the science of pedagogy and was launched without a complete understanding of the nature of learning.

We now have confidence that the technological tools McNamara wanted to use for academic improvement have little to no impact, and that real improvement requires a social infrastructure geared towards remedial education.

An M1A2 Abrams tank from 1st Battalion, 63rd Armor Regiment, “Dragons,” 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, Kansas, pulls during Combined Resolve X at the Hohenfels Training Area, Germany, May 1, 2018. Exercise Combined Resolve X is a U.S. Army Europe exercise series held twice a year in southeastern Germany. The goal of Combined Resolve is to prepare forces in Europe to work together to promote stability and security in the region. (U.S. Army photo by Spc. Andrew McNeil / 22nd Mobile Public Affairs)

To be sure, the brief period covered by the FSPC is not enough to remedy decades of educational shortfalls, but a better understanding of the problem (often linguistic) brings the ends and the means closer together.

Finally, while graduates of the Future Soldier course usually find themselves in armor, infantry or artillery (traditionally the lowest scoring specialties), there is little evidence thus far that their performance is meaningfully lower than that of other recruits. Project 100000 hurt the combat capacity of American units in Vietnam, and hurt the individuals who made up those units; there is no evidence thus far that FSPC will have the same effect.

The U.S. Army: How Do We Recruit in 2025?

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has argued that an end to “wokeness” and a wave of patriotism spurred by the election of President Trump to a second term is driving recruiting success in the US armed forces.

It’s too early to conclude that the Secretary of Defense is wrong about these claims; President Trump’s election surely matters for many of the demographics (in particular those of the exurban South) that have historically filled out the armed forces.

However, the FSPC program has had a significant impact, one that is readily apparent in the numbers.

About the Author: Dr. Robert Farley

Dr. Robert Farley has taught security and diplomacy courses at the Patterson School since 2005. He received his BS from the University of Oregon in 1997, and his Ph. D. from the University of Washington in 2004. Dr. Farley is the author of Grounded: The Case for Abolishing the United States Air Force (University Press of Kentucky, 2014), the Battleship Book (Wildside, 2016), Patents for Power: Intellectual Property Law and the Diffusion of Military Technology (University of Chicago, 2020), and most recently Waging War with Gold: National Security and the Finance Domain Across the Ages (Lynne Rienner, 2023). He has contributed extensively to a number of journals and magazines, including the National Interest, the Diplomat: APAC, World Politics Review, and the American Prospect. Dr. Farley is also a founder and senior editor of Lawyers, Guns and Money.

More Military

The First 48 Hours of a War With China ‘Could Be Ugly’

Russia Tried to Build Their Very Own F-22 Raptor. Calling It a Disaster Would Be a Gift

The Royal Navy’s Queen Elizabeth-Class Aircraft Carriers Simply Summed Up in 4 Words