Key Points and Summary – The A-10 Warthog earned devotion by saving lives at low altitude with a giant cannon and stubborn armor.

-But the Air Force is retiring it for five interlocking reasons: it can’t survive modern air defenses, it lacks the reach and speed today’s theaters demand, it performs a narrow mission in a budget that now favors multi-role jets, the fleet is old and costly to sustain, and precision weapons and sensors let other platforms deliver close-air support from safer ranges.

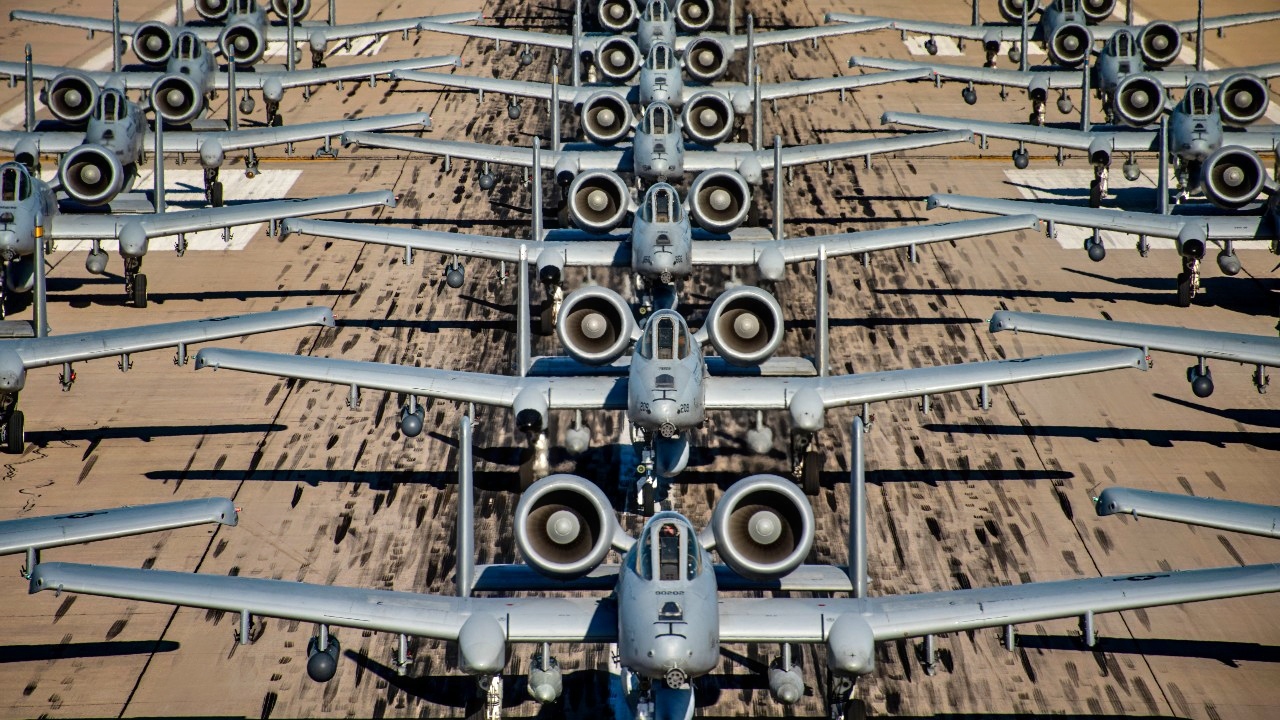

U.S. Air Force A-10 Thunderbolt IIs and an HC-130J Combat King II assigned to the 355th Wing taxi in formation on the runway at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona, Feb. 9, 2022. The 355th Wing maintains and operates A-10 Thunderbolt IIs, HH-60G Pave Hawks and HC-130J Combat King IIs ensuring its Airmen and aircraft are ready to fly, fight and win. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Alex Miller)

-Advocates rightly note the A-10’s loiter time, price, and psychological impact.

-Even so, in a contested world, retiring it is the right call.

The A-10 Warthog Needs to Be Retired (And That’s a Good Thing)

If you’ve ever talked to soldiers who heard the Warthog’s 30-millimeter growl overhead, you know why this airplane inspires loyalty bordering on love.

The A-10 was built for a world of Soviet armor and short distances, where a tough, slow, low-flying gunship could circle a firefight and make problems disappear.

That world is fading.

Why The A-10 Is Bowing Out

The new one is defined by long ranges, dense short-range air defenses, and precision sensors that punish predictable flight profiles.

The decision to retire the A-10 is not a verdict on its past; it’s a recognition that the battlefield it dominated has changed underneath it.

First, survivability.

The A-10’s strengths—low speed for accuracy, straight attack runs to employ the gun, predictable ingress—are exactly what modern air defenses exploit.

Short-range air-defense networks, shoulder-fired missiles, and radar-aimed guns now blanket front lines.

A-10 Warthog Bombs. Image Credit: National Security Journal.

A-10 Warthog National Security Journal Photo. Taken by Jack Buckby on August 23, 2025.

In the opening days of a high-end fight, flying low and slow near those systems is not bravery; it’s attrition.

When the threat picture spikes, commanders need aircraft that can sense first and shoot from a standoff while remaining hard to detect.

The A-10’s famous armor helps against small arms; it does not solve the missile problem.

Second, reach and tempo.

Contemporary operations—especially in the Indo-Pacific—stretch across vast distances. Tankers are finite and contested. You need jets that transit quickly, cover hundreds of miles between targets, and cycle weapons with minimal support.

The A-10’s cruise speed and range were designed for Europe in the 1970s, not oceans in the 2020s. In practical terms, that means fewer sorties where they are needed most, more tanker demand, and less flexibility when bases disperse.

Third, opportunity cost.

The Air Force no longer has the luxury of single-mission fleets. Budgets must buy aircraft that can swing from air-to-air to strike to electronic attack, and then share what they see over secure networks.

A-10s are superb at close-air support; they are not a credible answer for air superiority, long-range maritime strike, or suppression of enemy air defenses. Every dollar that keeps a specialized fleet alive is a dollar not buying multi-role mass where the force is thin.

Fourth, age and sustainment.

Re-winging and avionics refreshes extended the life of many airframes, but corrosion, fatigue, and parts obsolescence don’t bargain.

Keeping a small, elderly fleet mission-ready eats maintenance man-hours, depletes depots, and ties up training pipelines for crews who could be seasoning in aircraft the Air Force expects to fly for decades.

A-10 Warthog Cannon NSJ Photo. Taken at U.S. Air Force Museum on 7/19/2025.

A-10 Warthog National Security Journal Photo.

A GAU-8 Avenger 30mm cannon in the nose of an A-10 Thunderbolt II, assigned to the 442d Fighter Wing, at Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, April 9, 2021. The GAU-8 is a hydraulically-driven rotary autocannon capable of firing 3,900 rounds per minute with a variety of ammunition types for close air support missions. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Parker J. McCauley)

“Cheap to fly per hour” can be true on paper while still being expensive in practice when availability drops and cannibalization rises.

Fifth, the way close-air support is delivered has evolved.

Precision weapons, small-diameter glide munitions, networked targeting pods, and better digital links to ground controllers let fighters and gunships support troops from altitude and distance.

A pair of F-35s or F-16s, talking to a joint terminal attack controller with a digital map and laser designator, can place a weapon through a window without diving into a MANPADS envelope.

AC-130 gunships, attack helicopters, and armed drones add options at night and in weather.

The core effect—responsive, precise fires in contact—no longer requires a low, straight pass and a cannon burst.

What Fills The Gap

No single airplane replaces the A-10’s personality. Instead, the mission becomes a team sport. Stealth fighters use passive sensors to find threats and suppress them. Legacy fighters carry large stacks of precision weapons and share what they see.

Special operations gunships orbit with surgical guns and small glide bombs. Army attack helicopters and loitering munitions push fires right to the treeline. Uncrewed aircraft loiter where a pilot shouldn’t, relaying full-motion video and delivering lightweight weapons. The glue is data: secure, resilient links that allow a ground controller to task the best shooter in minutes, not the nearest one.

That may feel bloodless to those who remember talon-scraping, dust-blowing A-10 passes. But the aim is the same: keep friendlies alive and end the fight quickly—now with less risk of losing a crewed jet to a $50,000 missile.

The Best Counterarguments—And Why They Don’t Tip The Balance

The case to keep the A-10 isn’t frivolous. Advocates point to the jet’s phenomenal loiter time close to the fight, its tough skin and redundant systems, the shattering psychological effect of the GAU-8 cannon, and the relatively low operating cost compared with stealth aircraft.

They argue there will still be permissive wars—counterinsurgency, disaster response, border security—where an A-10 is the perfect screwdriver for a common screw. Some note the airplane’s ability to use rougher airstrips and work alongside ground commanders with a kind of shared rhythm newer jets haven’t had time to develop.

Those points deserve respect. They just don’t survive contact with the pacing threats that drive force design. The cannon’s terror fades against modern armor and active protection. Loiter near the front line is meaningless if getting to the front line requires flying through a thicket of missiles.

“Cheap per hour” ignores the cost-per-effect when a non-stealth jet must be escorted, tanked, and protected by jammers to do work a low-observable aircraft can do alone. And training the next generation of aircrews to excel at a niche platform has an opportunity cost when the Air Force needs them fluent in the kill webs of tomorrow.

If the mission truly requires a low-and-slow, small-arms-resilient presence—border zones, counter-drug, or permissive peacekeeping—there are cheaper turboprop solutions outside the Air Force inventory, and joint partners who specialize in them.

The United States should keep access to that kind of capacity. It shouldn’t freeze it into a bespoke jet that can’t survive the wars we most fear.

The Right Call In A Hard Decade

Nostalgia is not a strategy. The A-10 earned the bronze plaques and the battlefield tattoos. It also represents a design bet from half a century ago.

The Air Force is making a different bet now: that the next war will punish anything slow, predictable, and loud in the electromagnetic spectrum; that range, sensing, and teamwork will matter more than raw toughness; and that crews are safer when the airplane can see first and shoot from farther away.

Retiring the A-10 is not about forgetting the troops it saved. It’s about protecting the ones who will call for help tomorrow. Honor the Warthog for what it did. Then buy what the future demands.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

Why the U.S. Navy Finally Said No to the F-14 Tomcat

China’s ‘New’ J-35A Air Force Stealth Fighter Suffers From 1 Big Disadvantage

China’s Stealth Submarine Fleet Has a Message for the U.S. Navy

The U.S. Army’s Drone Nightmare Is Coming True

Mach 6 ‘Miracle’ SR-72 Darkstar Has a Message for Russia or China