Key Points and Summary – China’s J-20 “Mighty Dragon” went from rumor to reality in a little over a decade, and it hasn’t stopped evolving.

-Born from a push to counter U.S. airpower and shaped by lessons—sometimes stolen—from abroad, the program fielded its first jets in 2017–2018 and is now expanding with upgraded engines and a rare two-seat stealth variant.

China J-20 Fighters. Image Credit: Weibo.

J-20 Stealth Fighter. Image Credit: PLAAF.

-The J-20’s role is more than dogfights: it is a long-reach sensor-shooter meant to police the Western Pacific’s airspace and threaten support assets.

-Against the F-22 and F-35, it trades some close-in agility for range, radar reach, and networking. The result: a maturing, scalable stealth ecosystem.

J-20 Mighty Dragon: Why China Wanted a Jet Like This

Beijing’s basic problem was simple: U.S. and allied fighters, sensors, and tankers dominate the Pacific’s air routes. To change that math, China needed a jet that could sneak into contested airspace, see farther than fourth-generation fighters, and strike first—ideally while staying beyond the reach of defending missiles.

It also needed to be a platform family, not a one-off science project: a jet that could mature into multiple variants, use domestic engines, and plug into a fast-growing web of Chinese airborne sensors, long-range missiles, and surface-based air defenses.

The J-20 Mighty Dragon is that answer—a heavy, twin-engine stealth fighter intended to push U.S. tankers, surveillance planes, and escorts back from the first island chain, complicate carrier operations, and give China’s commanders an option to contest the sky without firing the first shot.

Where American fifth-generation jets grew up inside a global alliance network, the J-20 is China’s attempt to build one of its own.

The Origin Story—And What Was Borrowed Along the Way

The J-20’s roots reach into the 1990s “J-XX” studies. The outlines—long nose, canards, internal weapon bays—hinted at a different design philosophy from America’s tailless F-22 and the single-engine F-35.

China’s design bureaus were chasing the same physics but with different constraints: limited domestic engine technology at first, a desire for range, and a determination to move fast.

China J-20 Mighty Dragon in 2021. Image Credit: Chinese Internet.

Two forces accelerated that movement. The first was access to foreign ideas. U.S. prosecutions in the 2010s documented cyber-theft targeting advanced aircraft programs, including the F-22 and F-35, and a Canadian-arrested middleman later pled guilty in a U.S. court.

While a stealth jet can’t simply be copy-pasted from stolen files, such breaches can steer decisions—what shapes to try, which materials and sensor concepts are promising, where to avoid dead ends. The second force was Russian influence—notably the MiG 1.44 program.

Analysts have long noted the family resemblance: canard-delta shaping, broad internal volume, and solutions for inlets and bays that look more inspired by than identical to the Russian prototype.

Put simply: China watched, learned, and then iterated.

From Prototype to Patrols

China moved quickly from first flight (2011) to service entry (2017–2018). Early jets reportedly relied on imported or interim domestic engines; later airframes adopted improved Chinese powerplants. The People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) began assigning J-20s to frontline brigades, first for training, then for long-range patrols over water.

By the mid-2020s, public sightings of multi-ship J-20 formations, mixed-force training, and routine maritime flights made one thing clear: this is no hanger queen. It’s a fleet.

China J-20 Fighter. Image Credit: Chinese Air Force.

The tactical pattern is telling. China uses the J-20 as a sensor-led hunter, not a close-in knife fighter: approach quietly, build a picture, threaten from a distance, and let long-range missiles or other assets finish the job. That posture plays to the jet’s strengths—stealth, endurance, and sensor fusion—while sidestepping its likely weaknesses in a tight turning fight against a seasoned opponent.

Design Choices That Define the Jet

The J-20’s shape reflects China’s priorities. The canard-delta planform—forward foreplanes plus a broad triangular wing—buys lift and internal fuel volume, which translate into range and payload.

That choice complicates stealth because moving canards can bounce radar energy in unhelpful directions; China’s answer is careful edge alignment, coatings, and mission profiles that keep the jet pointed to minimize signature.

Diverterless inlets help hide the engine face (a radar “hot spot”) and reduce parts count. A faceted electro-optical sensor under the nose and an obvious infrared search-and-track (IRST) blister on the forward fuselage add passive detection channels that don’t broadcast the jet’s position.

Inside, the J-20 depends on a modern active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar, passive sensors, and a fusion backbone that stitches it all into a single picture.

That’s the difference between a stealth-shaped fighter and a fifth-generation weapon system: the pilot acts less like a stick-and-rudder ace and more like a node manager, deciding what to see, what to share, and when to strike.

Engines: The J-20A’s Big Leap

For years, the J-20’s Achilles’ heel was engine issues. Imported Russian engines and stopgap domestic models limited thrust, fuel economy, and reliability.

Over the past two years, that story has shifted. Imagery and reporting show WS-15 engines—China’s long-promised “definitive” powerplant—flying in J-20A prototypes and moving toward frontline use. The WS-15 isn’t a magic wand, but it promises more thrust and better thermal/power margins, which unlocks range, climb, and sensor cooling headroom. In short: the engine room is no longer holding the airframe hostage.

J-20A Fighter in Yellow. Image Credit: X Screenshot.

China J-20A Fighter in the Sky. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Engine maturity is a marathon, not a sprint. What matters now is whether WS-15 production and sustainment can keep up with fleet growth without quality dips. If they can, the J-20A becomes the baseline, not an exotic unicorn.

The Twin-Seat J-20S: A Different Kind of “Second Crew”

China did something neither the U.S. Air Force nor Navy has done with their stealth fleets: it built a two-seat variant. The J-20S isn’t a trainer in the classic sense. The back-seater is there to manage electronic warfare, sensor triage, and—most importantly—unmanned teammates. Think of swarming decoys, loyal-wingman drones, or reconnaissance assets that need an on-scene quarterback. That human second brain reduces workload spikes and adds tactical creativity when the sky is dense with emitters and threats.

If the J-20S enters widespread service—and early signs suggest it’s moving that way—China gains a man-machine teaming laboratory that can evolve fast. The effect isn’t just a new jet; it’s a doctrine accelerant.

Weapons and Tactics: What the J-20 Brings to a Fight

A stealth fighter without the right missiles is a sports car with economy tires. The J-20’s standard pair looks to be the PL-15 for long-range intercepts and the PL-10 for close-in snaps, both using modern seekers and datalinks.

The long-reach game is where the J-20 is designed to live: build tracks silently with radar and IRST, then push shots at tankers, surveillance planes, and fighters before they can respond. Reports of an even longer-range PL-17/PL-XX class weapon reinforce that strategy—make the sky unsafe for the high-value aircraft that make U.S. and allied tactics possible.

The J-20 can also carry precision strike stores internally for stealthy surface attack. That gives Chinese commanders a flexible “Day One” option against radars, command nodes, or ships—especially when paired with offboard targeting.

F-22 vs. J-20: A Tale of Two Philosophies

Put the F-22 Raptor next to the J-20 and you’ll notice two things: the American jet is smaller and cleaner, with no canards and exquisite shaping; the Chinese jet is larger and rangier, with extra internal volume and a layout that trades a bit of stealth simplicity for lift and fuel.

In a neutral merge with equally trained pilots, the F-22’s raw kinematics, signature control, and cockpit visibility likely win at close range. But that’s not where either side wants to fight.

A U.S. Air Force F-22 Raptor assigned to the 90th Fighter Squadron soars over Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson during ARCTIC EDGE 2025 (AE25), Aug. 18, 2025.

At beyond-visual-range, outcomes swing on who sees first, who manages emissions better, and who carries the better missile for the opening salvo. The J-20’s concept is to push the fight outward, leverage long-range shots, and stay away from a turning contest with Raptor-class opponents.

The F-22’s counter is newer U.S. missiles, better datalinks, superior training depth, and a mature maintenance ecosystem. It’s chess, not boxing.

F-35 vs. J-20: Systems vs. Scale

The F-35 is a multirole stealth workhorse with an unmatched global sustainment network and a cockpit built around fused situational awareness. Against it, the J-20 trades some of that software maturity for range and altitude performance, plus a likely advantage in payload of long-range air-to-air weapons per sortie.

If a fight comes down to coalition data-sharing and joint targeting, the F-35’s ecosystem is hard to beat. If it comes down to keeping distant tankers, patrol planes, and ships honest, the J-20’s reach is a real problem.

An F-35A Lightning II fighter jet, a single seat, single engine, all-weather stealth multirole fighter aircraft, assigned to the 466 fighter squadron prepares to taxi across the flightline at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, Oct. 5, 2024.

The longer this comparison runs, the less it’s about single-jet specs and the more it’s about ecosystems: tankers, standoff munitions, airborne warning aircraft, resilient datalinks, and the ability to generate sorties day after day.

Production Pace and Basing: The Quiet Advantage

Numbers matter. The J-20 is no longer a boutique fleet. Satellite photos, unit conversions, and Chinese official statements point to accelerating production, with new final-assembly capacity coming online and multiple brigades receiving the type.

Dispersed basing across China’s coastal and interior regions means the jets can threaten the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea, and deeper Pacific lanes without telegraphing movement. Just as important, China is fielding new tankers and improving ground support, which turn range on paper into combat radius in practice.

Quantity is its own quality. Even if each individual J-20 trails the F-35 in software maturity or the F-22 in raw agility, enough J-20s, well supported and well networked, change the calculus.

What’s Next: Three Arrows on the J-20’s Future

Arrow one: engines. If WS-15 production stabilizes, the J-20A becomes the norm. That raises performance, lowers operating headaches, and makes sustained patrol tempo more realistic.

Arrow two: teaming. The J-20S is the clearest public hint that China intends to fly manned-unmanned packages routinely. Expect more talk—and eventually images—of stealthy drones handing the Mighty Dragon a longer spear.

J-20S Fighter from X Screenshot. Image Credit: X.

China J-20S Fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Arrow three: software and electronic warfare. The hardest part of a fifth-generation fleet is invisible: fusion, counter-fusion, and emissions control. If we start seeing China conduct large, quiet “no-comms” exercises with J-20 packages, that’s a sign their software is maturing.

In Two Words: J-20 Powerhouse

Is the J-20 “as stealthy” as an F-22? That’s the wrong question. The right one is whether the J-20 is stealthy enough to do the missions China cares about—pushing out U.S. support aircraft, stalking patrol zones, escorting its own bombers and drones, and presenting dilemmas in the Western Pacific.

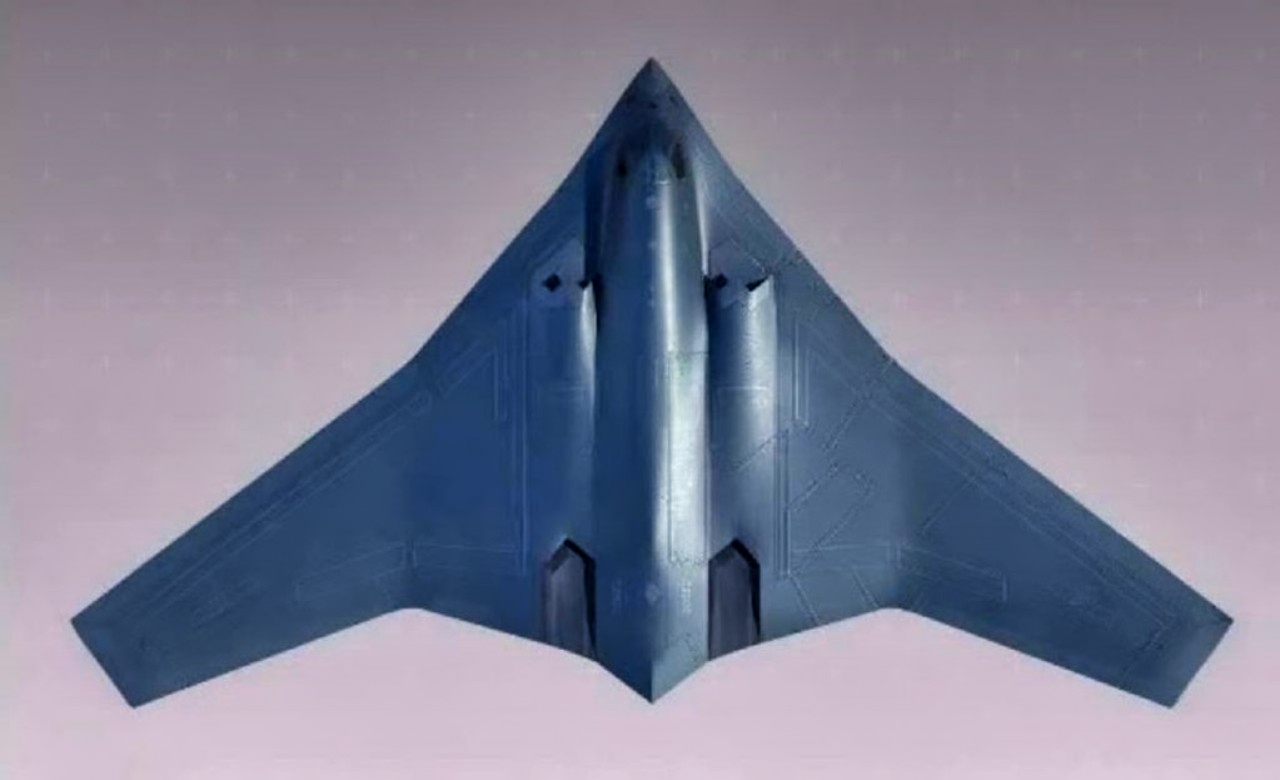

H-20 Bomber from China Artist Rendition. Creative Commons.

On that score, the answer increasingly looks like yes.

The program’s arc—from fast entry into service to engine upgrades and a distinctive twin-seat variant—shows a country willing to learn in public and fix in flight. If the J-20A with WS-15 becomes the standard and the J-20S scales, the “Mighty Dragon” will be less about single-jet duels and more about how China wages air warfare as a system.

That’s the metric U.S. and allied planners should track most closely.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University. Email Harry: [email protected].

More Military

The ‘Super’ B-52J Stratofortress Bomber Is Coming

The Air Force’s ‘New’ B-1B Lancer Super Bomber Is Coming Soon

‘Flying Dorito’: The A-12 Avenger II Stealth Bomber Summed Up in 1 Word

Never Finished: USS Illinois Is the U.S. Navy’s ‘Scrapped’ Iowa-class Battleship

Shel

October 26, 2025 at 3:03 pm

What real world warfighting experience does China have utilizing the new airframes, sensors and datalink technology? Having great gear is only good if you can use it effectively in the “fog of war”.

tim williams

October 27, 2025 at 4:58 pm

It is a beauty of a plane for sure. I fear the Chinese more than Russia when it comes to doing crazy things to bring fear in the world in regard to nuclear and standard warfare.