Key Points and Summary – NASA Planned a Mach 15 X-43D. It Never Flew — and That Matters Now.

-NASA’s X-43A proved that an air-breathing scramjet could fly at hypersonic speeds, reaching Mach 7 and Mach 9.6 in 2004.

X-43A Test Image. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-The natural next step was a follow-on vehicle known as X-43D: a hydrogen-fueled scramjet demonstrator designed to reach about Mach 15 and gather flight-environment and engine data that ground tests simply could not provide.

-That vehicle was studied, sketched out, and then quietly shelved as programs and budgets shifted.

-In an era when Russia and China field hypersonic systems, the decision not to move from X-43A to a Mach 15 demonstrator looks less like a footnote and more like a warning.

The Mach 15 X-Plane That Never Left the Drawing Board

When people talk about NASA’s Hyper-X program, they usually stop at the X-43A: a squat black wedge that rode a Pegasus booster to Mach 7 and then Mach 9-plus before diving into the Pacific. That’s the headline achievement.

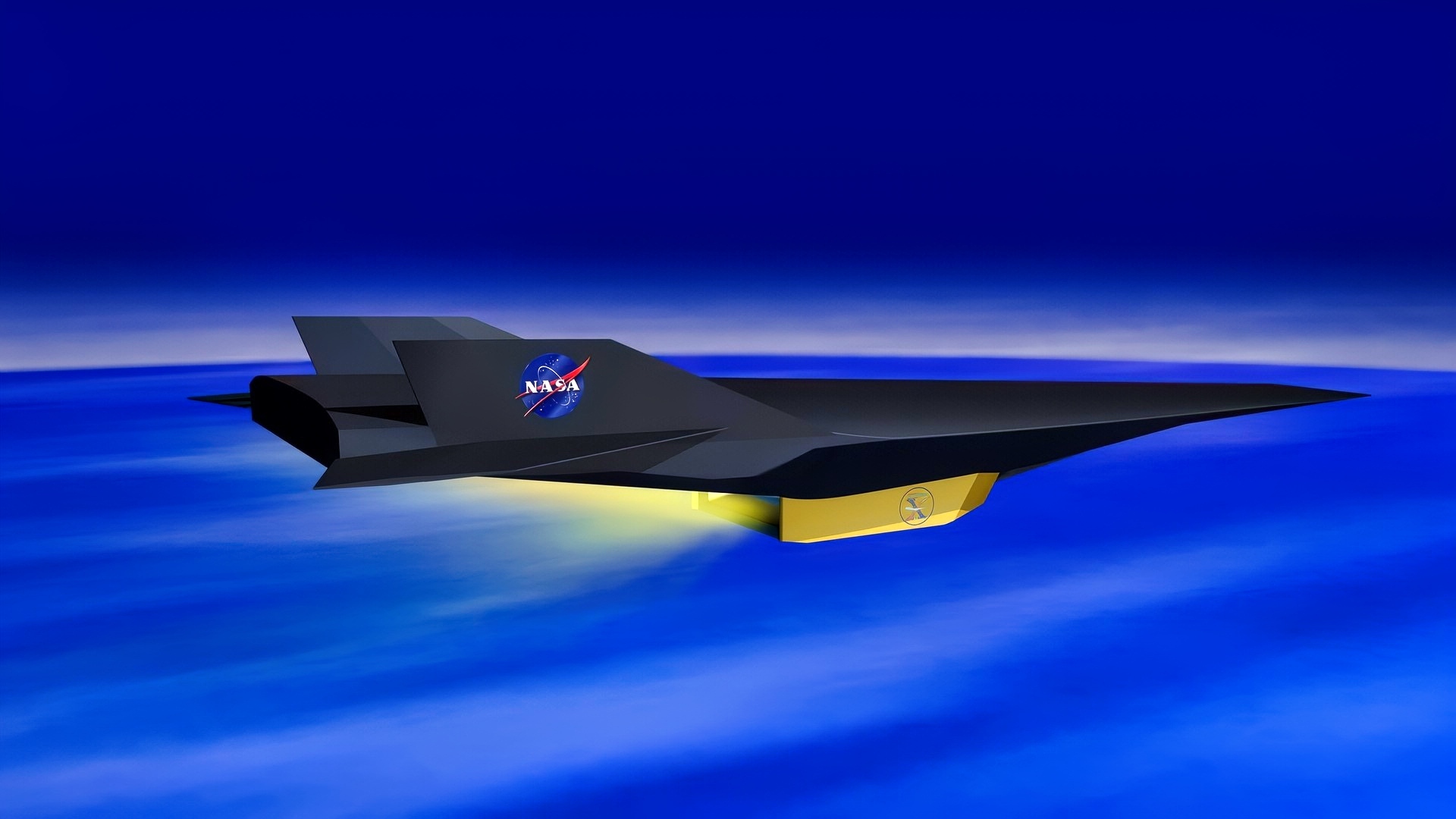

What almost never gets mentioned is the logical next step that was actually laid out in NASA planning documents: a Mach 15 follow-on vehicle called X-43D. It was conceived as a direct descendant of X-43A — another small, unpiloted testbed with a hydrogen-fueled scramjet, designed to push from the “mere” hypersonic regime into accurate hypervelocity flight.

You referred to it as X-15D, and you can see why. Conceptually, it sat at the intersection of the old X-15 rocket plane tradition and the X-43A’s air-breathing experiment. But in NASA’s own paperwork, the designation was X-43D, and it remained in feasibility studies and viewgraphs rather than ever flying.

In the age of Russian glide vehicles and Chinese hypersonic missiles, that gap is worth thinking about.

From X-43A’s Ten Seconds of Fire to a Mach 15 Roadmap

The starting point is still the X-43A.

In 2004, NASA flew two successful Hyper-X missions.

In each case, a B-52 dropped a Pegasus-based booster with the X-43A perched on its nose.

The stack climbed and accelerated; the experimental vehicle separated; a hydrogen-fueled scramjet lit for roughly ten seconds; then the wedge-shaped aircraft glided to a planned impact in the Pacific.

Those flights set records for air-breathing aircraft, validating scramjet operation around Mach 7 and then near Mach 10, and providing engineers with real flight data rather than just tunnel runs and simulations.

Inside NASA, that was never supposed to be the end of the story. Hyper-X, and the broader hypersonics roadmap tied to it, assumed that a Mach 7–10 demonstrator was only one rung on the ladder. Higher-speed, hydrogen-fueled scramjet testing was already penciled in.

That is where X-43D came in.

What X-43D Was Actually Supposed to Be

NASA’s Next Generation Launch Technology (NGLT) program, working with the Pentagon’s Director of Defense Research and Engineering, commissioned a conceptual design and feasibility study for what it explicitly called “X-43D.”

In those documents, X-43D is described very clearly:

-A Mach 15 flight test vehicle using a hydrogen-fueled scramjet engine.

-Closely related to X-43A in overall configuration, but optimized for much higher speed.

-Intended to operate briefly in powered mode, then glide, just as X-43A did — but in a far harsher environment.

-Focused on gathering “high Mach number flight environment and engine operability information which is difficult, if not impossible, to gather on the ground.”

So What Happened?

NASA and its contractors put real analytical muscle into the concept.

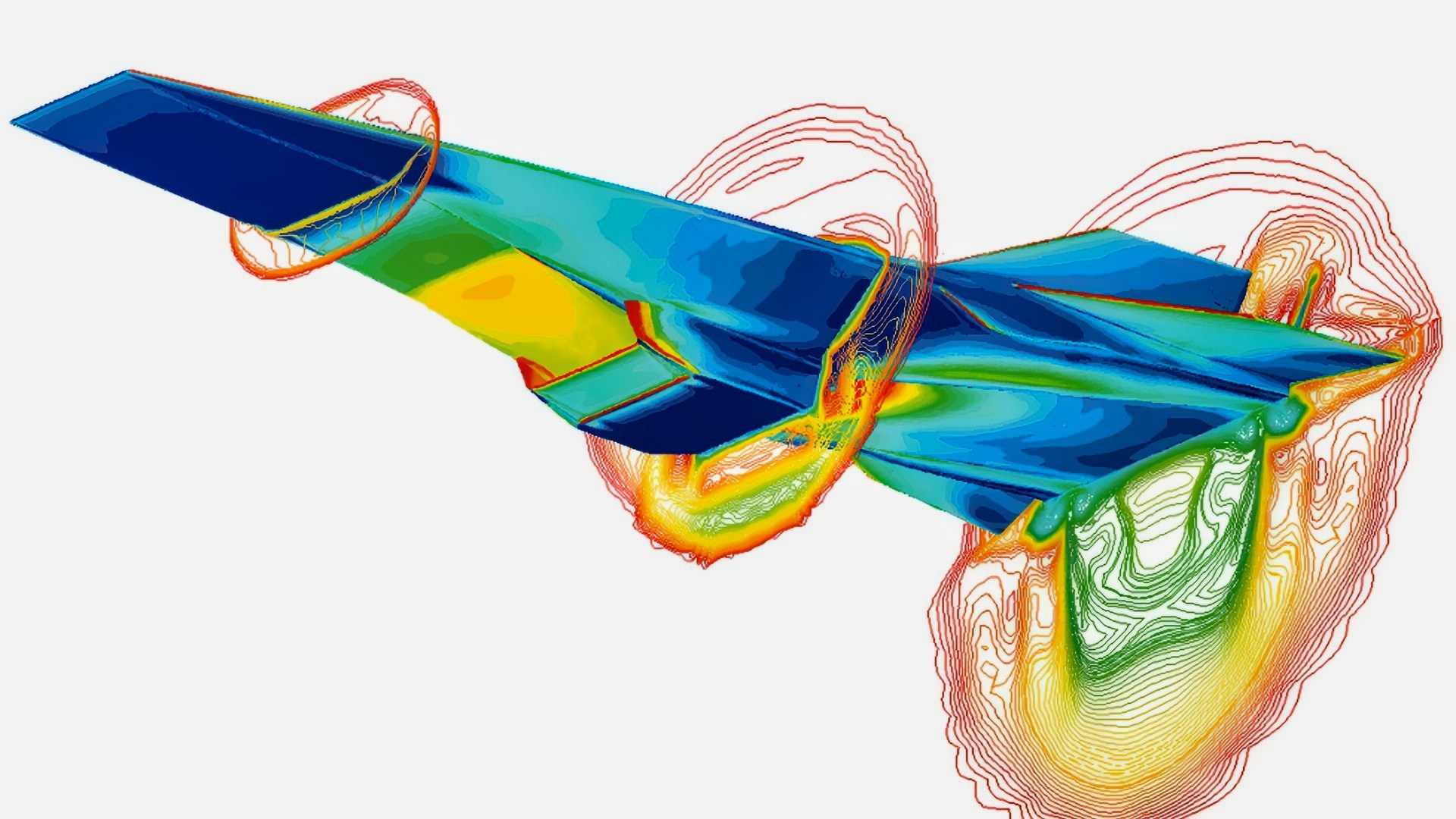

The feasibility study discusses the multidisciplinary nature of the design problem: at Mach 15, the underside of the vehicle serves as both a wing and an engine duct, the thermal protection system is inseparable from the structural design, and small changes in geometry affect both lift and combustion.

Separate strategy papers on advanced space transportation and hypersonic propulsion fold X-43D into a broader technology roadmap. In that roadmap, Hyper-X proves Mach 7–10 scramjet flight; X-43D follows as a hypervelocity (around Mach 15) hydrogen-fueled demonstrator; and that, in turn, reduces risk before any near–full scale reusable system is attempted.

One NASA planning document is blunt: the Mach 15 X-43D is “required risk reduction” for future high-Mach scramjet systems.

Outside NASA, even simple outreach material reflected the idea. A Smithsonian “How Things Fly” explainer notes that X-43D was envisioned as a Mach 15 follow-on, and that it never progressed beyond feasibility study.

In other words, this was not a fan-art fantasy. It was a defined, if still early, NASA-DoD concept.

Why It Stayed a Study

So why did we never see an X-43D bolted to a booster under a B-52?

The answer is prosaic: timing, budgets, and shifting institutional priorities.

B-52 Stratofortress, 40th Expeditionary Bomb Squadron, loaded with 12 Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) heads toward Iraq with it’s new mission directive. The bomber’s mission is to provide close air support for coalition troops stabilizing the country of Iraq, April 15, 2003. Operation Iraqi Freedom is the multi-national coalition effort to liberate the Iraqi people, eliminate Iraqi’s weapons of mass destruction and end the regime of Saddam Hussein. (U.S. Air Force photo by Tech. Sgt. Richard Freeland) (Released)

The core Hyper-X flights wrapped just as NASA’s broader portfolio was being restructured. NGLT itself was wound down. Hypersonics funding and leadership moved around between NASA, the Air Force, DARPA, and later the services’ weapons programs. In that churn, X-43D’s status never advanced beyond “formulation”; the vehicle was designed and analyzed on paper, but never authorized as a full flight program.

A NASA hypersonics overview from Langley’s Vehicle Analysis Branch notes that X-43B, X-43C, and X-43D all received substantial design support — and that none of them made it to flight before the program was cancelled.

X-43A from NASA. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

X-43A NASA. Image Credit: NASA.

The United States did not walk away from hypersonics entirely. The Air Force’s X-51A Waverider, for example, picked up the scramjet baton and eventually achieved several minutes of powered flight around Mach 5.

But the specific hole where X-43D was supposed to be — hydrogen scramjet flight at roughly Mach 15 — remained a hole.

What That Means in a Hypersonic Arms Race

Two decades later, we live in a very different strategic environment.

Russia fields its Avangard hypersonic boost-glide vehicle on intercontinental missiles.

China has publicly paraded the DF-17, a medium-range system paired with a hypersonic glide vehicle designed for use in the Western Pacific.

U.S. budget documents and Congressional research reports talk openly about catching up in hypersonic boost-glide and hypersonic cruise missiles.

None of those weapons is a hydrogen-fueled scramjet aircraft. Most are boost-glide systems riding ballistic rockets. But the underlying problem set — materials, aerothermodynamics, guidance, and control at very high Mach numbers — overlaps heavily with what X-43D was designed to explore.

NASA and DoD never claimed that flying X-43D would magically deliver operational weapons. What they did say, very clearly in their own planning, was that a Mach 15 demonstrator would provide flight-environment and engine-operability data that ground tests could not, and that this data was “required risk reduction” before larger, more ambitious hypersonic systems were attempted.

Instead of taking that step when the analytical work was fresh and the Hyper-X momentum was real, the United States left X-43D in the feasibility-study phase and allowed other priorities to take over.

The X-43D Could Have Changed the Hypersonic Game?

The X-43A story is familiar: short flights, historic Mach numbers, and a dramatic splashdown. The X-43D story is quieter: a Mach 15 hydrogen-fueled scramjet demonstrator, defined on paper, tied explicitly into a national hypersonic roadmap — and then canceled before it ever left the drawing board.

You do not have to speculate wildly to see what was lost. NASA’s own documents spell it out: X-43D was supposed to be the high-Mach risk-reduction step between record-setting experiments and truly operational hypersonic systems. That step never happened.

In an era when Moscow and Beijing now fly hypersonic weapons for effect, the gap between what the X-43A actually did and what X-43D was meant to do has turned into more than a historical footnote.

It is a reminder that even when the United States wins the race to a new speed regime, there is no guarantee it will stay on the track long enough to turn those ten seconds of fire into lasting advantage.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

JASSM: The ‘Stealth’ Cruise Missile That Keeps Russian Generals Up at Night

The Day a B-2 Stealth Bomber Disintegrated on Takeoff

The U.S. Military’s Superpower Muscles Are Getting Old

The Mach 6.7 X-15 ‘Hypersonic Rocket Plane’ Has a Message for the U.S. Air Force

ThaDewd

November 25, 2025 at 8:31 am

This needs to happen