Key Points and Summary – In 2005, workups off California, Sweden’s AIP-powered HMS Gotland (built for around $100,000,000) reportedly penetrated the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan’s (built for around $6,000,000,000) screen and registered simulated torpedo “kills,” exposing how hard modern diesel-electrics are to detect and track.

-The U.S. Navy responded by leasing Gotland (2005–2007) as a full-time sparring partner in San Diego, giving carriers, destroyers, P-3/P-8 crews, and MH-60R squadrons live reps against a truly quiet boat.

(October 30, 2007) – USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) conducts Board of Inspection and Survey (INSURV) following a six-month Planned Incremental Availability (PIA). All Naval vessels are periodically inspected by INSURV to check their material condition and battle readiness. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class (AW) M. Jeremie Yoder.

-The lesson wasn’t that aircraft carriers are obsolete; it was that air-independent propulsion and patient SSK tactics demand layered, disciplined, team-based ASW.

-The experience helped catalyze upgraded sensors, multistatic tactics, and a culture that treats quiet adversaries as the default.

When HMS Gotland Humbled A Navy Aircraft Carrier—and Rebooted U.S. ASW

In 2005, a small, diesel-electric submarine from Sweden forced the most powerful navy on earth to rethink some very basic assumptions. During pre-deployment workups off Southern California, HMS Gotland reportedly penetrated the defensive screen of Aircraft Carrier Strike Group 7, lined up on USS Ronald Reagan, and registered multiple “kills” with exercise torpedoes before slipping away. No fireworks. No skyline of smoke. Just a periscope, a camera, and the cold arithmetic of probability.

As an editor and think tank researcher for several publications and institutions over the years, I was utterly shocked when I came across this story a decade ago.

The story has been told—and retold—for years. But when you strip away the internet lore, what remains is more interesting than a meme: a practical demonstration that air-independent propulsion (AIP) submarines in skilled hands can be maddeningly hard to find, and that the U.S. Navy, after a decade of post–Cold War ASW atrophy, needed reps against exactly that threat.

The Navy responded the right way—by leasing Gotland and her crew for two full years of sparring out of San Diego—because AIP boats were proliferating and the fleet needed hard lessons fast.

(Oct. 1, 2005) – The Swedish diesel-powered attack submarine HMS Gotland transits through San Diego Harbor during the “Sea and Air Parade” held as part of Fleet Week San Diego 2005. Fleet Week San Diego is a three-week tribute to Southern California-area military members and their families. U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class Patricia R. Totemeier (RELEASED)

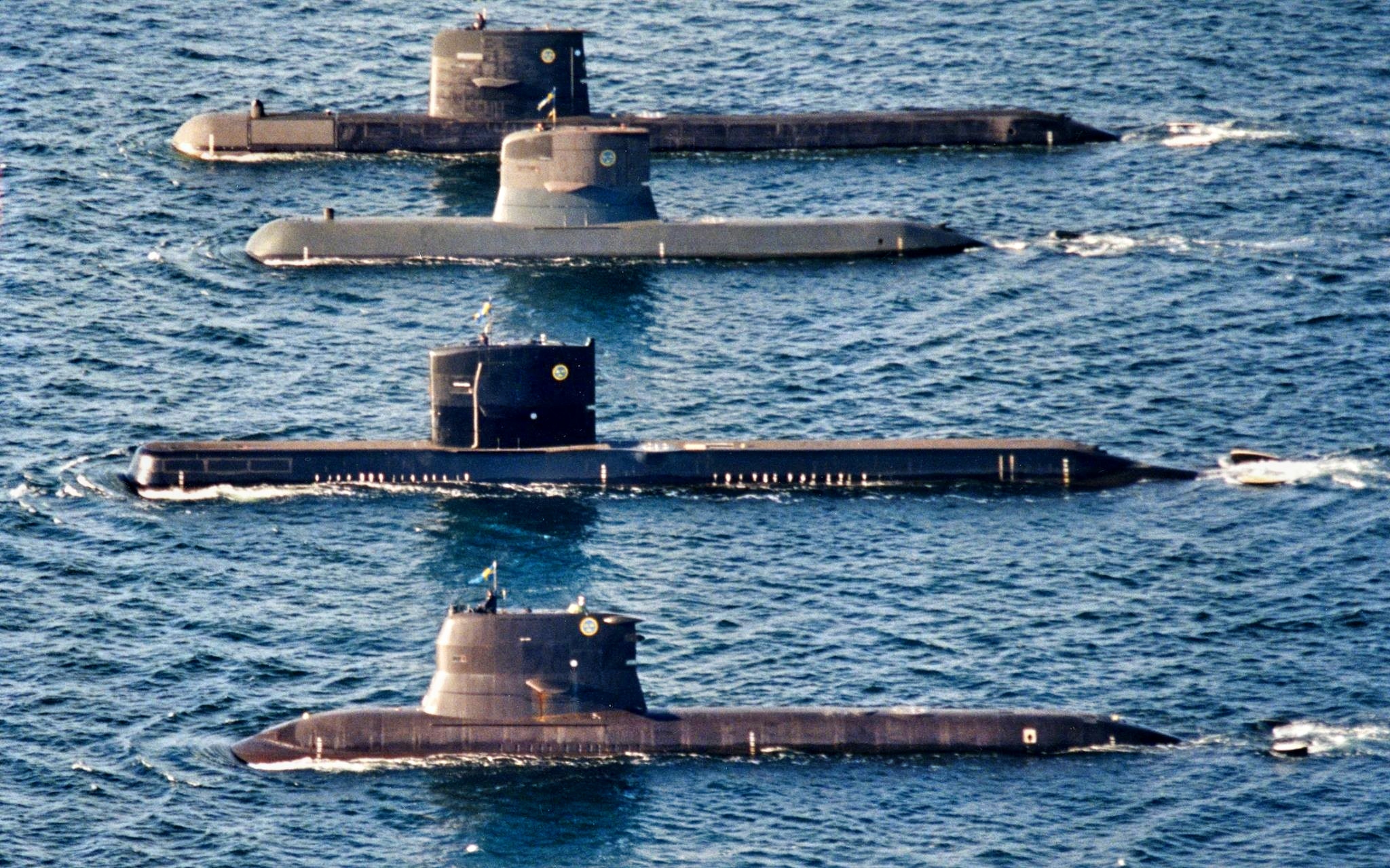

Gotland-Class Submarines. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

What follows is the deeper look: how Gotland pulled off its party trick, why AIP was so disruptive at the time, why the episode surprised the U.S. Navy, what the two-year lease accomplished, and why the lessons still matter in an era of distributed sensors, long-range anti-ship weapons, and crowded littorals.

Why Gotland Was A Different Kind Of Quiet

If a nuclear submarine wins by endurance and speed, a modern AIP boat wins by silence at tactically useful endurance. Classic diesel-electrics are whisper-quiet on battery but must snorkel regularly to run diesels and recharge—noisy work that also makes them easier to detect.

Sweden’s Gotland-class changed the game in the mid-1990s by integrating Stirling-engine AIP, a closed-cycle external-combustion system fed by liquid oxygen that can generate electrical power while fully submerged. The payoff isn’t high speed; it’s days to weeks of low-speed, nearly vibration-free underwater operation without exposing a snorkel mast.

That matters because the underwater battlefield is run on probabilities. Every snorkel is a detection opportunity—by radar, infrared, electronic support measures, even visually. Every hour that a sub can loiter without snorkelling, hugging layers and bottom contours, is an hour the surface force must search a wider volume with fewer clues. Add in anechoic coatings, machinery isolation, and a propulsion line optimized for steady, low-RPM running, and you get the kind of acoustic profile that humbles even good passive sensors, especially in littoral water with mixed salinity, bottoms that scatter sound, and shipping noise that masks signatures.

Sweden designed for exactly that environment. The Baltic is a sonar engineer’s nightmare: shallow, busy, variable. The Gotland-class was optimized from first principles to be hard to hear there. Those design habits came with the boat to California.

How A Small Sub Stole A March On A Big Deck Aircraft Carrier

Exercises aren’t prize fights; they’re scripted to teach. But within the exercise’s rules, Gotland played its hand well. The “recipe” was textbook SSK tradecraft: pick an approach corridor the carrier must traverse, sit still and listen while the strike group creates its own acoustic clutter, exploit layer conditions, and move only in short, thought-out bursts. At very low speed on AIP, Gotland’s acoustic signature was so small that passive sensors had little to chew on; active sonars could search, but the Pacific’s coastal shallows and the need to protect the air wing’s tempo can limit how aggressively you ping.

Pacific Ocean, July 25, 2005 – USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) performs a high speed run during operations in the Pacifc Ocean. Ronald Reagan and Carrier Air Wing One Four (CVW-14) are currently underway conducting Tailored Ships Training Availability (TSTA). Official US Navy Photo by Photographers Mate 1st Class James Thierry. (RELEASED)

The carrier’s screen, to be clear, is no slouch: destroyers and cruisers with towed arrays and variable-depth sonars, helicopters with dipping sonars, maritime patrol aircraft laying buoys, and—often—cooperating submarines. However, antisubmarine warfare is a team sport with time pressure. In 2005, the U.S. team had spent the better part of a decade focused on land wars and maritime security tasks, rather than stalking quiet littoral SSKs. When Gotland reached periscope depth inside the inner ring and clicked the shutter on aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan, the message landed: we need more at-bats against boats like this.

The Shock Was Real—And So Was The Response

The Navy didn’t sulk. It wrote a check. In March 2005, the United States and Sweden signed a memorandum to base Gotland and her Swedish crew in San Diego for a year of bilateral training—an arrangement extended through 2007. The deployment, often referred to informally as the Swedish Submarine Deployment, turned the little AIP sub into a full-time sparring partner for aircraft carrier groups, destroyer squadrons, P-3C/P-8A crews, and MH-60R helicopter detachments rotating through workups on the West Coast.

The logic was simple: there is no classroom substitute for a live, modern AIP opponent. Gotland played OPFOR in composite training units, joint task force exercises, and bespoke ASW events, while U.S. crews iterated on tactics—sonobuoy patterns, multistatic active techniques, towed array employment in challenging bottoms, and the choreography of air-surface-submarine cueing. The submarine also forced relearning of basics: speed discipline in the screen, emissions control to deprive the sub of cueing, patient tracking over fast sweeping, and accepting the geometry that sometimes the only honest way to sanitize a lane is to put another submarine in it.

An F/A-18C Hornet, assigned to the “Stingers” of Strike Fighter Squadron 113, transits over the haze of southern Afghanistan. VFA 113, part of Carrier Air Wing 14 aboard the aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan is supporting Operation Enduring Freedom. The mission of CVW 14 is to protect the people of Afghanistan and to support coalition forces. Ronald Reagan is currently deployed to the U.S. 5th Fleet area of operations. Operations in the U.S. 5th Fleet area of operations are focused on reassuring regional partners of the United States’ commitment to security, which promotes stability and global prosperity.

Sweden, for its part, gained a lot from the deal: experience in warm-water acoustics, a deep look at American ASW processes, and data to inform its next-generation designs. Both sides won.

What Made Gotland Special At The Time

AIP was the headline, but Gotland brought a holistic quieting package:

Stirling-Engine AIP: Closed-cycle power generation underwater with minimal vibration, supplying the batteries without snorkeling.

Battery-Dominant Tactics: Use AIP to keep the batteries topped and the boat submerged for days; use batteries tactically for sprints or ultra-quiet creeps.

Compact Hull With Smart Isolation: Swedish practice emphasized resiliently mounted machinery, careful shaft-line design, and shock isolation.

Littoral Sensor Fit: A suite tuned for close-in work and target motion analysis in cluttered water, not just chasing open-ocean boomers.

A Mixed Torpedo Battery: Standard heavyweight 533-mm weapons paired with smaller 400-mm tubes give flexibility for different engagements and training.

None of this made Gotland “better” than a U.S. nuclear boat in an absolute sense. It made her disproportionately dangerous in cluttered water and painfully survivable in certain geometries—exactly the kind of geometry you get near choke points, straits, and coasts.

Aircraft Carrier Shocker: Why It Surprised The U.S. Navy

By 2005, the U.S. surface force and air wing hadn’t had enough live reps against truly quiet SSKs. The end of the Cold War and a long focus on land campaigns meant ASW funding, manning, and training intensity declined. Many Cold War tools (e.g., some towed arrays and low-frequency active systems) aged out or were spread thin; expertise concentrated in pockets. AIP boats, meanwhile, were proliferating: Germany’s Type 212/214 families, Sweden’s exports, Japan’s Stirling-equipped boats (and later lithium-ion designs), South Korea’s programs—navies around the world were fielding SSKs with week-long submerged endurance and soft acoustic edges.

Taigei-Class Submarine from Japan. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Taigei-Class Submarine from Japan. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Gotland was, in that sense, both a wake-up call and a gift. It surfaced—pun intended—a training gap and then stuck around to help close it.

The Exercises Were Real—And So Were The Constraints

Exercises impose rules. OPFOR subs often get mission tasking with the benefit of hindsight: they know roughly where and when the high-value unit must pass; their job is to stress the screen and expose seams. Carrier strike groups often work under constraints (air-plan tempo, training objectives) that complicate pure ASW focus. And “sinking” a carrier in an exercise means achieving a firing solution and recording evidence; in a war, that final run to weapon release might be the most dangerous minute of a sub’s life.

All true—and none of it erases the core lesson. If conditions that are common in the real world (busy water, time pressure, imperfect cueing) let a high-end AIP boat routinely get inside the screen, the fleet has work to do. That was the point of keeping Gotland in San Diego for two years.

What The Navy Changed After Two Years With Gotland

Some of the response was hardware: refreshed towed arrays and variable-depth sonars for surface combatants; a sharpened transition from P-3C Orion to P-8A Poseidon with multistatic sonobuoys; acceleration of the MH-60R’s full ASW kit; investment in multistatic active tactics that use separate source and receiver buoys to light up quiet targets; and renewed enthusiasm for putting U.S. submarines into the sub-hunter role in carrier workups. Training syllabi were surely updated; doctrine and playbooks were likely rewritten with AIP-specific considerations in mind.

Equally important was mindset. Crews relearned to think like the quiet adversary: stay patient, assume the SSK has more time than you do, and refuse to be rushed into noisy, high-speed searches that help the submarine more than the screen. Commanders revisited emissions control, de-cluttering the acoustic environment and denying the sub free cueing. And the Navy built more live sparring into its calendar—through continued bilateral work with foreign SSKs and the long-running Diesel-Electric Submarine Initiative (DESI) with partner navies.

Why AIP Proliferation Still Changes The Math

The global trend that made Gotland a useful sparring partner has only accelerated. Many navies now field AIP or near-AIP endurance SSKs, some with lithium-ion batteries that transform the sprint-and-drift tradeoffs, others with mature Stirling or fuel-cell plants. They are cheap compared to nuclear boats, can be built or bought in small numbers by regional navies, and are tailor-made for sea denial in straits, archipelagos, and coastal bastions. Against a high-value force that must operate near land to put aircraft in range—or to force contested sea lanes—those SSKs offer an adversary the chance to trade time for position.

The U.S. answer isn’t to panic about aircraft carriers; it’s to layer defenses and distribute risk—push the air wing’s reach (tankers, long-range weapons), fill gaps with manned and unmanned ASW platforms, and keep expanding the fleet’s acoustic picture with fixed and mobile arrays. The Gotland episode didn’t say “carriers are obsolete.” It said “carriers must be escorted by a navy that trains, equips, and fights as if quiet SSKs are everywhere.”

What Gotland Meant For Sweden

For Sweden, Gotland’s American tour was a validation at scale. The boat’s AIP philosophy—born in the Baltic—proved relevant in blue-water training against the biggest fleet afloat. The data and experience fed directly into modernization of the Gotland-class and into the design of Sweden’s next-generation A26 (Blekinge) class, which doubles down on stealth, modular payload options, and long endurance without snorkeling. It also cemented Sweden’s reputation as a thinking person’s submarine builder: small boats, smartly engineered, optimized for the water they fight in.

Aircraft Carrier Myth, Memory, And The Message That Endures

Did a $100-million diesel boat really “sink” a $6-billion carrier? In the construct of an exercise, yes. Does that mean a single SSK would inevitably kill a U.S. supercarrier in war? No. It means what the Navy took it to mean in 2005: don’t underestimate quiet, patient adversaries; don’t let ASW proficiency atrophy; and fight the fleet you’re up against, not the one you prefer.

That’s the legacy of Gotland’s two years in San Diego. The little sub from the Baltic didn’t change the Navy’s center of gravity overnight. It did something quieter and more durable: it helped the fleet remember that silence is a capability—and that the surest way to beat it is to train against it, relentlessly.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

The U.S. Navy’s Big Aircraft Carrier Mistake Still Stings

Russia’s Big Su-57 Felon Stealth Fighter Mistake Still Stings

Why the F-111B Fighter Still Haunts the U.S. Navy