Key Points and Summary – The Soviet Union built revolutionary titanium-hulled submarines—like the Alfa-class—that were faster and could dive deeper than any American sub.

-The U.S. Navy, however, never copied this strategy. It was a deliberate choice.

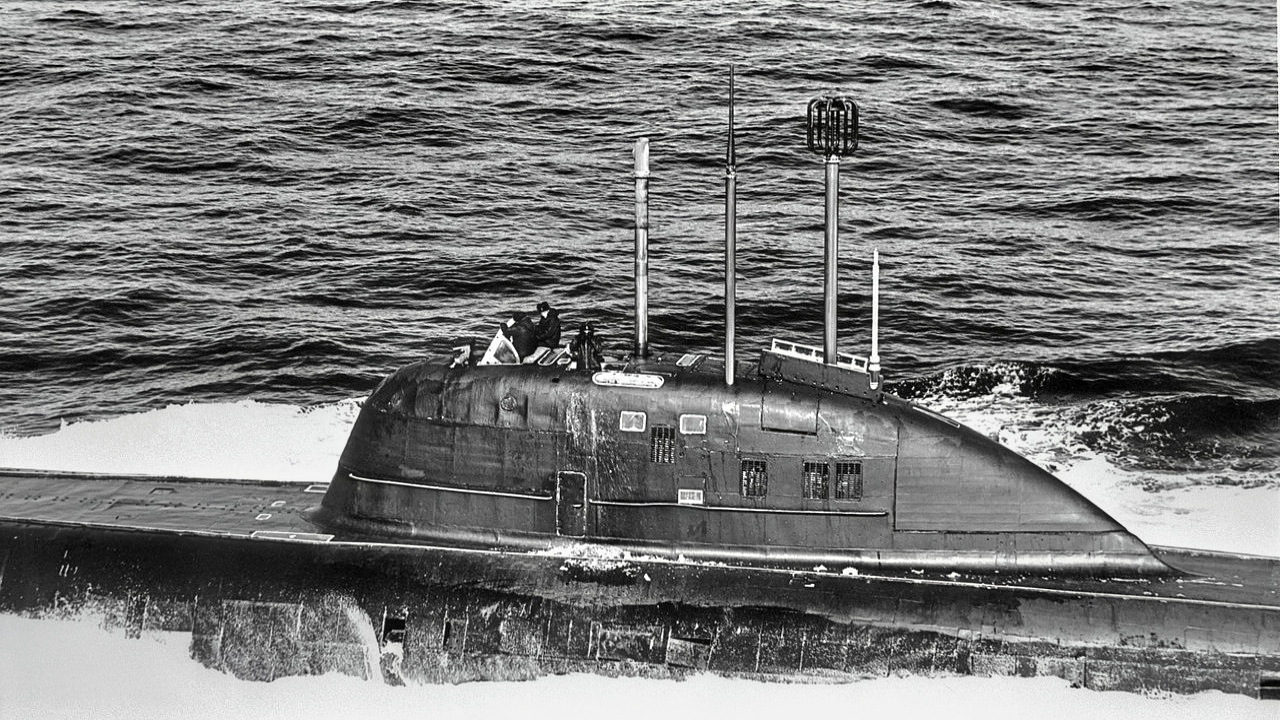

Sierra II-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

-The U.S. correctly identified that the very things making Soviet subs fast, like their liquid-metal reactors, also made them incredibly loud.

-America instead invested everything in acoustic stealth, building a larger, cheaper, and far quieter fleet of steel submarines.

-It was a victory of philosophy: the U.S. chose to be the silent hunter, proving that in underwater warfare, invisibility is infinitely deadlier than speed.

Russia’s Titanium Submarines Make You Stop and Think

During the Cold War, it seems Moscow was never great at building consumer goods that people wanted, but they could build military machines that terrified the West.

In fact, the Soviet Union pulled off a technological feat that, to this day, boggles the mind.

They did what no other nation, before or since, has ever managed to do at scale: they built entire classes of attack submarines forged from titanium.

When I was a kid, I was obsessed with these submarines, and I would sit in various libraries all over Rhode Island, where I grew up, reading any book or magazine I could get my hands on that had what little data was available. Yes, before the internet.

These boats were the stuff of legend and of Western nightmares. The most famous was Project 705 Lira, known to NATO as the “Alfa-class,” a vessel that became a near-mythical monster in the public imagination, most notably as the silent, deadly adversary in The Hunt for Red October.

But the Alfa was just the beginning. It was followed by the lone “Mike-class,” the two “Papa-class” boats, and the more refined, production-line “Sierra-class.”

These titanium sharks were, on paper, untouchable. They were lighter, stronger, and faster than anything in the water. They could dive to crushing depths where our torpedoes couldn’t follow and sprint at speeds that left our own hunter-killers churning in their wake.

They were also non-magnetic, a quality that threatened to make our most reliable method of submarine detection—the Magnetic Anomaly Detector (MAD)—all but useless.

Sierra-Class-Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

And yet, the United States Navy, with its near-limitless budget and technological mastery, looked at this incredible leap… and passed. We never built a single titanium-hulled attack submarine.

This decision is one of the most misunderstood and brilliant strategic choices of the 20th century. It was not a failure of technology or a lack of resources. It was a conscious, deliberate, and profound choice, a rejection of a spectacular and seductive technology in favor of a far less glamorous but infinitely more lethal philosophy.

The U.S. Navy understood something that the Soviets, in their obsessive pursuit of performance, seemed to have missed: in the dark, silent world of undersea warfare, it doesn’t matter how fast you are if you are screaming your location to the enemy. We didn’t build titanium submarines because we had chosen a different path.

We had chosen to be silent.

The Siren Song of Titanium

To understand the American decision, you first have to appreciate just how tempting the Soviet achievement was. For submarine designers, titanium is a dream material. It has a strength-to-weight ratio that is off the charts, far superior to even the high-tensile steel (like HY-80 and HY-100) that the U.S. Navy had perfected for its own hulls.

This simple fact of metallurgy unlocked a whole new world of performance.

First, and most famously, there was speed. Because a titanium hull is so much lighter than an equivalent steel one, a submarine could be driven to astonishing velocities with the same amount of power. The Alfa-class was the ultimate expression of this, a 41-knot (nearly 50 miles per hour) underwater interceptor.

It was a submarine that could, quite literally, outrun an American Mark 48 torpedo. This was a terrifying tactical proposition. How do you kill an enemy you cannot catch?

Second, there was depth. The immense strength of the titanium alloy allowed Soviet designers to build hulls that could withstand pressures the West could only imagine. While our Los Angeles-class boats had a test depth reportedly in the realm of 1,000 feet, the titanium Alfas and Sierras had operational depths estimated at 2,500 feet or more.

This was not just for bragging rights; it was a profound tactical advantage. They could dive into a deep-water layer where sonar performance was poor and, more importantly, they could go to depths where our torpedoes simply could not operate. They could use the abyss itself as an impenetrable shield.

Mike-Class Submarine from Russia. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

Finally, there was the “black magic” of low magnetism. Steel-hulled submarines are, fundamentally, giant magnets moving through the Earth’s magnetic field. This creates a detectable disturbance, which is what the Magnetic Anomaly Detectors (MAD) on our sub-hunting planes, like the P-3 Orion, are designed to find. But titanium is non-ferrous. It has almost no magnetic signature. This threatened to render one of our key anti-submarine warfare (ASW) tools completely obsolete.

For the Soviet Navy, this combination was the key to solving their core strategic problem. They were, geographically, a “land-locked” naval power. Their primary fleet, the Northern Fleet, was penned up in the Barents Sea, and to get to the open Atlantic, they had to sprint through a gauntlet of NATO listening posts and attack subs. For them, speed and depth were not luxuries; they were survival.

They expected to be detected. Their entire doctrine was to “go fast” and “go deep” to break through the blockade and hunt our carriers. The titanium submarine was the perfect interceptor for this brute-force strategy.

The American Heresy: Choosing Silence Over Speed

The U.S. Navy looked at this entire picture and came to a completely different conclusion. Our strategic geography was the opposite. We were a maritime power with open access to two oceans. Our submarines were not interceptors; they were persistent, long-range hunters. They were the invisible “wolf packs” that would quietly slip into the enemy’s backyard and lie in wait, undetected, for weeks or months at a time.

From this philosophical starting point, the American naval command developed a culture that became a near-religious obsession: acoustic stealth.

In the murky, three-dimensional world of undersea combat, sound is everything.

It is the only thing that travels. The boat that makes less noise than the background hum of the ocean itself, and has the sonar to hear the other guy, is the one that wins. Every single time. The U.S. Navy understood this instinctively. Speed, in our doctrine, was a liability. Going fast creates noise. It creates a massive “bow wave” as the submarine pushes through the water, and it makes the propeller churn and “cavitate”—a sound like a freight train to a sensitive passive sonar.

So, while the Soviets were pouring their treasure into titanium, the U.S. was pouring its own into the dark art of quieting. We developed technologies that were, in their own way, just as exotic. We pioneered the use of “anechoic tiles”—thick rubberized coatings for the hull that absorb an enemy’s active sonar pings (making the sub a “black hole”) and, more importantly, dampen the noises from inside the boat.

K-278 Komsomolets Mike-Class. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

We mastered the science of “machinery rafting.” Instead of bolting a noisy engine or generator directly to the submarine’s hull, we mounted them on massive, multi-ton steel platforms, which then rested on a complex system of rubberized shock absorbers. These “rafts” isolated the vibrations, preventing the hull from becoming a giant speaker, broadcasting the submarine’s presence to the entire ocean.

And we put our “exotic” money into things like propulsion. We developed and milled incredibly complex, skewed propellers that could move massive amounts of water with minimal cavitation. This is why, when the Los Angeles-class submarines came out, they were a quantum leap. They were so much quieter than their Soviet counterparts that it was almost unfair. We could hear them coming from hundreds of miles away. They, on the other hand, wouldn’t know we were there until a torpedo was already in the water.

The Titanium Trap: A Loud and Costly Dead End

This American obsession with silence is what exposed the fatal flaw of the Soviet titanium program. The very technologies that made the Alfa-class so fast also made it deafeningly loud.

Its revolutionary power plant —a lead-bismuth-cooled reactor —was a compact, high-performance marvel. It was also a symphony of noise. Its pumps had to operate at incredible pressures, creating a unique, very loud acoustic signature that American sonar operators quickly learned to identify. The sub’s lightweight titanium hull, while strong, was also highly “elastic.”

It was a fantastic conductor of sound, vibrating like a drum and broadcasting every internal noise out into the water. The Soviets’ machinery rafting technology was, at the time, decades behind our own.

So, what we had was a “super-sub” that could go 41 knots but was, at that speed, perhaps the loudest object in the ocean. And even at a “quiet” patrol speed, it was significantly noisier than a Los Angeles-class boat. The U.S. Navy’s assessment was clear: why on earth would we build a submarine that could outrun a torpedo, when we could just build a submarine that would never be shot at in the first place?

And then, there was the cost. This, more than anything, is the factor that doomed the titanium submarine. It wasn’t just that titanium was expensive to buy, which it was. It was a nightmare to build. You cannot weld titanium in the open air; the oxygen in the atmosphere contaminates the weld, making it brittle and weak. The Soviets had to build entire, massive, climate-controlled factory halls that were filled with inert argon gas, where workers in specialized suits could painstakingly piece these hulls together. It was a slow, toxic, and astronomically expensive process.

Alfa-Class Submarine Creative Commons Image.

The human cost was also immense. The liquid-metal reactors were notoriously temperamental and dangerous. They had to be kept hot at all times, even in port, or the liquid metal coolant would solidify, expand, and destroy the reactor, turning the submarine into a solid block of radioactive slag. This made them a maintenance nightmare and incredibly dangerous for their crews.

The U.S. Navy, by contrast, had perfected the art of building with steel. Our shipyards at Electric Boat and Newport News were optimized for it. We had an entire industrial base built around it. To switch to titanium would have meant spending trillions of dollars to rebuild our entire submarine-building infrastructure from the ground up.

And for what? To gain an advantage—speed—that our entire naval philosophy deemed a secondary, almost useless, metric compared to stealth. The U.S. didn’t just dodge a bullet; we refused to even play the game. We let the Soviets win the “race to 40 knots” while we were busy winning the real war: the war of silence.

The Steel Shark That Proved the Point

The final verdict on this technological-doctrinal debate was written in steel: the U.S. Los Angeles-class and its successors. These steel-hulled boats, built at a fraction of the cost of their titanium rivals, could be produced in large numbers.

We built 62 of them. They were quieter, had better sonars, and were crewed by the best-trained sailors in the world.

In the deep-ocean duels of the 1980s, the Los Angeles-class was the undisputed king. It could sit quietly, listen, and gain a complete firing solution on a Soviet boat—even a titanium Alfa—long before the Soviet commander ever knew he was in danger.

The Soviet strategy of “sprint and hide” was a failure, because our silent steel sharks were already waiting for them when they started their sprint.

The Soviets themselves eventually admitted defeat. After the experimental Alfas, Papas, and Mikes, and the handful of Sierras, they returned to building with steel. Their next great class of attack submarine, the Akula-class, was a steel-hulled boat that finally incorporated the Western-style quieting technologies (many stolen by the Walker spy ring) that the U.S. had perfected.

In a profound historical irony, the Akula—a steel boat—was far, far quieter and a much more dangerous threat than the exotic titanium Alfas that preceded it.

Titanium Fail?

The Soviets had built a few exquisite, spectacular, and fatally flawed “show cars.”

The United States built a massive fleet of lethal, reliable, and invisible “pickup trucks.” The ultimate lesson of the titanium submarine is a timeless one: do not be seduced by spectacular performance.

The most effective weapon is not the one that breaks records, but the one that masters the fundamental rules of its environment. In the ocean, that rule is, and always will be, silence.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University. Email Harry: [email protected].

More Military

China’s H-20 Stealth Bomber Has a Message for the U.S. Air Force

China’s New J-35 Stealth Fighter Has a Message for the U.S. Air Force

China Is Studying the Ukraine War to Become a Drone Superpower

The Road to a China-America Nuclear War

China Could Fire Mach 6 Hypersonic Missiles from Bombers to Sink Navy Aircraft Carriers