Key Points and Summary – The Soviet Union built the Oscar-class (Project 949/949A) for one purpose: kill aircraft carriers at range with 24 P-700 Granit missiles guided by an ocean-wide reconnaissance network.

-The improved Oscar II-class added quieting and survivability but is forever tied to the Kursk tragedy.

-After the Cold War, the big SSGNs shifted to periodic exercises and, today, a modernization path (949AM) that swaps Granit for flexible Kalibr/Oniks—and potentially Tsirkon—turning a specialized carrier killer into a multi-mission standoff shooter.

-We break down why Moscow wanted it, how it was presented on paper, what happened to the Kursk, which hulls still sail, and how the Oscar fits alongside Russia’s new Yasen-M boats.

Russia’s Oscar-Class Submarines In 4 Words: Built to Kill Carriers

In late–Cold War planning, the Soviet Navy faced a blunt fact: the U.S. Navy’s aircraft carrier battle groups could reach into the Barents and the Pacific bastions, threaten SSBN patrol areas, and hold key military and industrial targets at risk.

Building a symmetrical blue-water carrier force was unrealistic. The Soviet solution was elegant in its own way: deny the sea to carriers with long-range, supersonic anti-ship missiles fired in overwhelming salvos—from aircraft, cruisers, and submarines—cupped by a space- and air-based targeting complex.

Enter Project 949 “Granit” (NATO: Oscar I) and quickly, the improved Project 949A “Antey” (Oscar II). These huge SSGNs carried 24 P-700 Granit (SS-N-19 “Shipwreck”) missiles in angled tubes outboard of the pressure hull, plus a heavyweight torpedo battery.

The missiles weren’t just fast; they were cooperative, designed to share targeting data mid-flight, assign roles within the salvo, and push home a terminal sea-skimming attack while others climbed to scout and cue. To see far enough to use that range, the Oscar plugged into Legenda—a broad targeting network of reconnaissance aircraft, surface pickets, and ocean surveillance satellites—with a distinctive mast receive antenna on the submarine. The result was a classic Soviet asymmetric play: leverage magazine depth and standoff to keep carriers out of the most sensitive waters.

From Oscar I To Oscar II: What Changed

The basic idea didn’t change—big missiles, big reach—but the platform matured. Oscar II lengthened the hull, refined the sail and control surfaces, improved quieting and survivability inside the familiar double-hull architecture, and upgraded sensors and combat systems. Twin reactors fed steam turbines on two shafts, giving speed in the low-30-knot range under water and endurance measured in months (food being the limit).

Because the 24 launchers are packed between the inner and outer hull, internal volume remained available for crew, machinery, and torpedo magazines. Up front, a mixed battery—typically four 533-mm and two 650-mm tubes—could fire heavyweight torpedoes, anti-submarine rockets, and mines.

Key specs (Oscar II, typical figures): length about 155 meters, beam ~18 meters, submerged displacement around 24,000 tons, test depth commonly cited around 600 meters, crew on the order of 100–130. These are ballpark public figures; the class spans multiple builds and refits, but the picture is consistent: very large SSGNs built to carry a very large salvo.

How The Oscar Was Meant To Fight

An Oscar II was envisioned as part of a layered maritime strike. Think of Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers with long-range anti-ship missiles, Kirov-class battlecruisers and Slava-class cruisers with heavy anti-ship batteries, and Oscars lurking forward of bastions in the Norwegian Sea or North Pacific.

External targeting—first through Legenda’s radar and ELINT satellites and today through the modernized Liana system (Lotos-S1 + Pion-NKS)—would push coordinates to the submarine, which would then ripple a pack of P-700s. Within the salvo, one or more missiles would climb to act as scouts and relays; the rest would stay low, leveraging speed, sea-skimming flight, and home-on-jam logic to tax Aegis defenses. The goal was not elegant ship-to-ship fencing; it was to mission-kill a carrier group by sheer weight and smarts in the first minutes.

About the P-700 Granit: open sources place its range in the ~500–625 km band depending on profile, with terminal speeds Mach 1.6–2.5+, a ~750 kg warhead (conventional or nuclear), and mixed-mode guidance with midcourse updates—a purpose-built carrier-group killer for the 1980s and 1990s.

The Kursk Tragedy: What Happened And Why It Matters

On August 12, 2000, K-141 Kursk, an Oscar II, suffered a catastrophic accident during a major Northern Fleet exercise in the Barents Sea. A practice 65-cm torpedo in the forward room catastrophically failed, with high-test peroxide (HTP) decomposition triggering an initial blast and a fierce fire. Minutes later, multiple warheads in the room detonated, destroying the bow compartments and driving the 24,000-ton submarine to the seabed at roughly 108 meters.

All 118 sailors aboard ultimately died—some in the initial explosions, others who survived the first minutes but succumbed to fire, flooding, and oxygen depletion while trapped aft. Notes recovered later—including the widely discussed Kolesnikov note—confirmed that men were alive in the after compartments for hours.

The rescue response became its own tragedy: delays in locating the sub, equipment problems in mating rescue assets to the aft escape trunk, and initial reluctance to accept foreign help. British and Norwegian divers opened the aft hatch days later; there were no survivors. The subsequent salvage—an epic Dutch-led engineering effort in 2001—cut off the shattered bow, drilled and fitted 26 lifting points to the pressure hull, and raised the boat beneath the barge Giant 4 for tow to dry dock. Investigators cited maintenance failures and hazardous torpedo fuel practices; Russian authorities later withdrew the HTP-fueled torpedo type implicated in the initial blast.

For the Oscar fleet, Kursk was a searing lesson in safety culture, rescue readiness, and the human cost of peacetime training risks.

After The Cold War: Long Patrols, Set-Piece Drills, Occasional Cameos

The 2000s were uneven: tight budgets, fires during heavy maintenance on some hulls, and periods of layup. But the class never disappeared. A memorable public sighting came in August 2020, when K-186 Omsk surfaced near Alaska during a major Russian exercise after earlier firing a cruise missile in the Bering Sea—a reminder that Oscar IIs still roam approaches to U.S. and allied waters. In the Barents, Oscar IIs fold into Northern Fleet live-fire drills, often alongside newer Yasen boats. In June 2024, the Northern Fleet publicly highlighted cruise-missile launches against sea targets from Orel (an Oscar II) and Severodvinsk (a Yasen-class), with Granit/Kalibr shots at roughly 170 km—a set-piece vignette of old and new working in tandem.

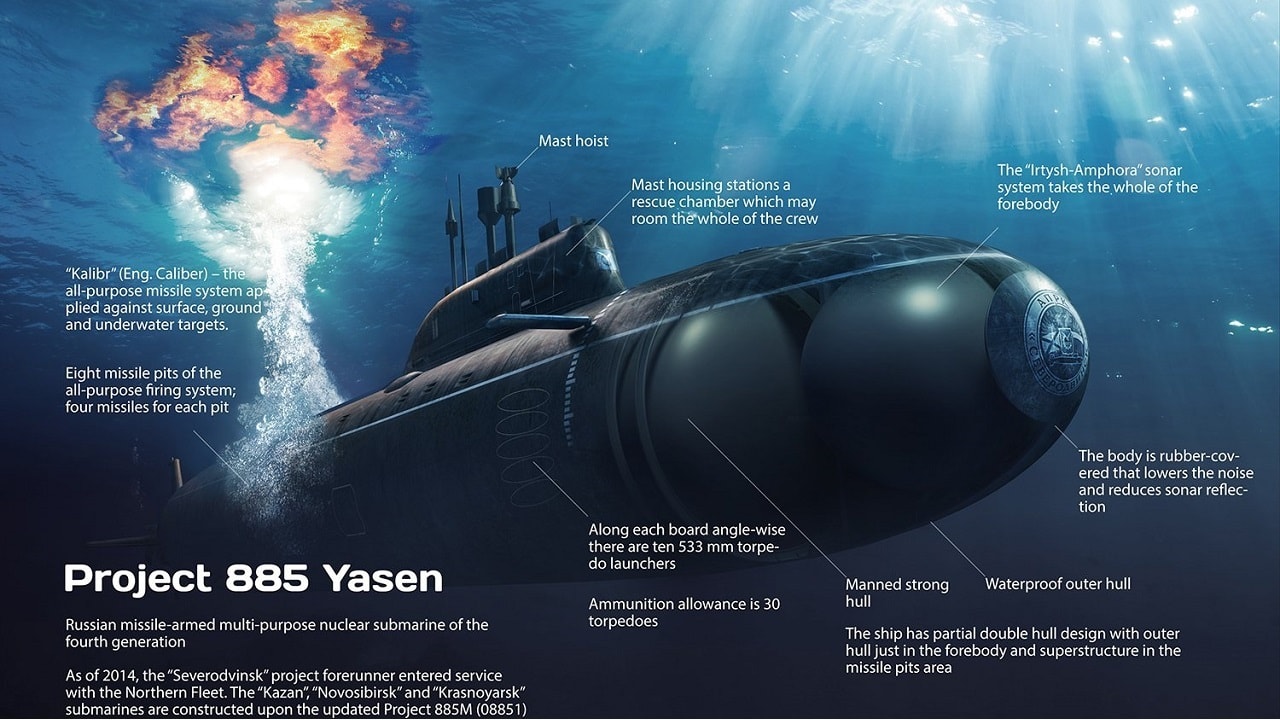

Yasen-Class submarine. Image Credit: Russian Government.

Operationally, what’s changed most since the 1990s is the target set. Russia’s navy has leaned hard into standoff land-attack in Syria and Ukraine using Kalibr family missiles from surface ships, diesel-electrics, and Yasens. The Oscar’s modernization is designed to join that club.

949AM Modernization: From Single-Purpose Hammer To Flexible Shooter

The heart of the 949AM refit is simple: swap the old P-700 tubes for modular launchers that can carry modern, smaller missiles. Public figures frequently cite capacity for up to 72 mixed rounds—think 3M-14/3M-54 Kalibr, P-800 Oniks, and, as Russian sources periodically assert, 3M22 Tsirkon (Zircon)—in place of the original 24 Granits. Beyond missiles, the work packages include modern combat systems, sonar/ESM, navigation/communications, and fire-control upgrades. The flagship Pacific Fleet hulls for this effort are K-132 Irkutsk and K-442 Chelyabinsk; schedules have slipped (deep refits always do), but the work continues at Zvezda and Zvezdochka.

If you strip away the acronyms, the concept is straightforward and strategically useful: keep the Oscar’s cavernous missile real estate, but make it agnostic. A refitted Oscar becomes a theater strike asset able to threaten ships or land targets at long range without closing to the most dangerous waters. That’s a better fit for Russia’s navy today, which often prefers standoff salvos over surface action in contested seas.

The Missile Brain: From Legenda To Liana

No long-range missile is better than its targeting. The old Legenda constellation—US-A radar ocean surveillance and US-P ELINT satellites—has long since aged out. Its successor, Liana, blends Lotos-S1 (passive ELINT) and Pion-NKS (active maritime reconnaissance) satellites, paired with air and surface sensors, to revive that ocean-wide picture. How robust Liana is at any moment is a matter of debate, but the direction is unmistakable: Russia wants its submarines to see farther and shoot smarter again. For Oscars, that’s everything—especially if they carry flexible load-outs under 949AM.

The Fleet Today: Who’s Sailing, Who’s In The Shed

Open-source information in 2024–2025 paints a practical picture:

Northern Fleet (Barents): K-266 Orel (active), K-410 Smolensk (active).

Pacific Fleet (Kamchatka): K-186 Omsk (active), K-150 Tomsk (active), K-456 Tver (typically listed active).

Modernizing: K-132 Irkutsk (949AM), K-442 Chelyabinsk (949AM).

Other notes: K-141 Kursk lost in 2000; K-329 Belgorod—a heavily modified Oscar hull—serves as a special-mission submarine (Poseidon carrier/host for deep-diving craft), not a standard SSGN.

Exact readiness churns with yard periods and crew rotations, but the takeaway is consistent: a handful of Oscar IIs remain operational while two Pacific hulls push through deep modernization.

How The Oscar-Class Compares Now—And Why It Still Matters

Against U.S. types, the Oscar II was never a Seawolf-style knife fighter and it isn’t a Virginia-class multitool. It was designed as a sledgehammer—a fast, survivable platform to ripple very heavy salvos. By modern standards, a big double-hull boat is easier to find and harder to hide than newer designs. Western ASW has evolved: P-8A patrol aircraft, improved multi-static sonars, seabed arrays, and allied undersea surveillance make life harder in the GIUK gap, Barents, and North Pacific.

USS Missouri Virginia-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

But naval warfare is also about magazines and geometry. A refitted Oscar II that can carry dozens of Kalibr/Oniks—and possibly later missiles—can influence a theater without sprinting into the tightest ASW nets. It can menace sea lines of communication, pressure amphibious or logistics groups, and strike land targets deep from relatively safe waters. In a crisis, one hull with a 40–70-round mixed magazine is strategically consequential.

The Kursk Legacy Inside The Community

Inside submarine forces, tragedies rewire habits. Kursk led to changes in torpedo policies, renewed attention to escape/salvage capabilities, and sharper yard safety during heavy work. Oscar crews drill material checks and casualty procedures with that memory in the room. The tragedy also shaped how Russia discusses accidents, accepts outside help, and manages public messaging around submarine events. None of that brings back the 118, but it lives on in how the fleet trains and deploys.

Future Paths: What To Watch

949AM Throughput. How many hulls actually finish deep refits? Two Oscar IIs modernized on each coast is a different threat than one or none. Yard capacity, sanctions, and budget will tell.

Missile Mix. Expect Kalibr/Oniks as the bread-and-butter. Tsirkon at scale on legacy hulls would be a watershed—but integration, testing, and doctrine all have to line up.

Targeting Maturity. The true value of long-range weapons hinges on Liana and associated ISR. If that picture tightens, Oscars matter more.

Yasen-M Production. As Yasen-M numbers grow, the Oscar role narrows—but doesn’t vanish. In the interim, the Oscar is the big stick Russia already has.

NATO Counter-Detection. Expect more multi-static fields, unmanned pickets, and seabed fixed sensors—increasingly hostile water for large SSGNs.

Bottom Line

The Oscar-class is a time capsule—and a warning. It came from an era when the Soviet Navy sought to erase carriers with massed, coordinated salvos. That DNA remains, but the platform is evolving: from single-purpose carrier killer to flexible standoff striker with room for modern missiles and modern targeting. The boats are old, big, and maintenance-hungry—but magazine depth at range still buys influence.

As long as a few Oscar IIs sail—and especially if 949AM yields a genuine 72-cell mixed load-out—the U.S. and its allies will keep a close ear tuned to the Barents, the Norwegian Sea, the Bering, and the Okhotsk. Somewhere out there, a long, slab-sided hull may be waiting for the call.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

688I: The U.S. Navy’s Best Attack Submarine?

Russia’s T-72 Tank Is So Obsolete

China Says It Can Kill B-21 Raider Bomber