Key Points and Summary – A U.S.–China war would likely begin not with a declaration, but with a chain of miscalculations.

-Five flashpoints stand out: a South China Sea confrontation that spirals; a Taiwan crisis that jumps from coercion to blockade or strikes; a clash around Japan’s Senkaku Islands; an unsafe aerial intercept that echoes the 2001 EP-3 collision; or a naval accident at sea involving warships at knife-edge range.

(August 15, 2008) With SH-60 helicopters moving pallets of supplies both USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) and USNS Bridge (T-AOE 10) work together during a replenishment at sea or RAS. With Reagan’s six galleys and approximately 4,100 Sailors it takes a lot of produce to feed that many folks and the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier got what it needed from USNS Bridge to do so.

The Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group is on a routine deployment in the 7th Fleet area of responsibility. Operating in the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean, the U.S. 7th Fleet is the largest of the forward-deployed U.S. fleets covering 52 million square miles, with approximately 50 ships, 120 aircraft and 20,000 Sailors and Marines assigned at any given time.

U.S. Navy photo by Senior Chief Mass Communication Specialist (SW/NAC) Spike Call

-Each scenario follows the same arc—friction, a mistake, then political pressure that narrows options.

-What keeps a spark from becoming a blaze is disciplined behavior, clear red lines, resilient hotlines, and de-escalation ladders that leaders actually trust.

5 Ways a U.S.–China War Could Start—And What Might Still Prevent It

Great-power wars rarely start with a formal decision to fight. They begin with a bump in the night, a misread signal, a domestic audience that demands resolve, and a military machine already moving. The U.S.–China competition is no exception.

Forces operate in proximity across the Western Pacific; both capitals issue deterrent signals that look provocative to the other; both depend on rapid decision cycles that leave little time for careful translation. In that environment, five flashpoints stand out. None guarantees war. Each provides a plausible path in which an incident becomes a crisis, a crisis becomes a test, and a test becomes a shooting war.

1) South China Sea: Gray Zone Friction Turns Red Hot

The South China Sea is the world’s busiest laboratory for coercion below the threshold of war. Coast guards, maritime militia, and navy escorts operate cheek-by-jowl around reefs, shoals, and drilling sites. Water cannons, lasers, ramming, near-collisions—these are the daily headlines. Now add U.S. freedom-of-navigation operations, allied patrols, and aircraft gathering intelligence along crowded air corridors.

J-10CE Fighter. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

How It Starts. A routine patrol meets an unusually aggressive intercept. A water-cannon blast disables a small ally’s ship; a blocking maneuver clips a U.S. destroyer’s bow; or a helicopter’s downwash knocks sailors into the sea. Lives are at risk. Radios crackle with accusations. Cameras are rolling.

Why It Escalates. Within hours, domestic outrage in the affected country forces public vows to defend sovereignty. Beijing sees an opportunity—or a trap. Washington faces alliance credibility questions. More ships surge to the area to “stabilize” the scene; more aircraft orbit overhead. In crowded, shallow waters, mass is not stability—it is a multiplier for mistakes.

The War Path. A warning shot meant to deter is misread as an attack. A damaged ship starts to sink; rescuers reach her only after a second collision. Missiles remain unfired—but not for long. A local commander, confident he is acting defensively, launches a short-range attack to force an adversary off. The political space for de-escalation narrows to a slit. Within a day, both capitals are weighing strikes outside the original incident area to restore deterrence—exactly how local sparks become regional fires.

What Could Prevent It. Clear, rehearsed rules of behavior between coast guards and navies; wider buffers around risky maneuvers; pre-agreed crisis call trees that open at the tactical level, not just leader hotlines; and visible third-party presence (for example, neutral rescue and medical assets) that lowers the political price of backing away.

2) Taiwan: Coercion Jumps The Guardrail

Crisis over Taiwan is the most discussed path to war—and perhaps the most elastic. The likely opening move is not an amphibious landing but a coercive campaign: no-notice exercises, missile overflights, cyberattacks, rolling air and sea patrols that create a quasi-blockade. Washington and partners respond with airlift, sanctions warnings, and persistent presence.

A U.S. Air Force F-16 Fighting Falcon assigned to the 54th Fighter Group soars through the sky over the Oscura Range at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico, April 21, 2025. During range operations, F-16 pilots perform munition drops and strafing maneuvers to test their abilities in the aircraft. (U.S. Air Force photo by Senior Airman Nicholas Paczkowski)

How It Starts. A “customs inspection” gambit at sea becomes a stop and seize of a commercial ship; a PLA fighter crosses into a no-go box and collides with a Taiwanese jet; missiles bracket the island and close key lanes. A misconfigured targeting packet, a corrupt navigation feed, or an overeager pilot turns an intimidation run into a deadly mistake.

Why It Escalates. Each side has red lines that are deliberately fuzzy. Taipei refuses to accept a de facto quarantine; Beijing refuses to accept what it sees as a challenge to sovereignty. U.S. leaders feel compelled to keep air and sea lanes open at least episodically—“freedom corridors” escorted by U.S. and allied ships and aircraft. The coercer’s logic and the defender’s logic collide.

The War Path. An escorting U.S. destroyer is targeted by a coastal battery’s radar and responds with soft-kill measures; a nearby missile boat perceives a threat and fires. The U.S. shoots down the incoming weapon; fragments kill sailors on a third country’s ship. The next day, the PLA launches longer-range salvos at airbases that supported the convoy; U.S. aircraft hit the radar that cued them. In 48 hours, a blockade crisis has turned into reciprocal strikes on the enablers of coercion: sensors, runways, tankers, drones.

What Could Prevent It. Quiet, pre-crisis corridor concepts—clearly advertised channels for humanitarian and commercial traffic with defined escort rules; multilateral penalties for violating corridor neutrality; and back-channel choreography that lets each side declare victory domestically while reducing the tempo of overflights and live-fires.

F-16 Fighting Falcons from the 35th and 80th Fighter Squadrons of the 8th Fighter Wing, Kunsan Air Base, Republic of Korea; the 421st Expeditionary Fighter Squadron of the 388th FW at Hill Air Force Base, Utah; the 55th EFS from the 20th FW at Shaw Air Force Base, S.C.; and from the 38th Fighter Group of the ROK Air Force, demonstrate an “Elephant Walk” as they taxi down a runway, during an exercise at Kunsan Air Base, Republic of Korea, March 2, 2012. The exercise showcased Kunsan Air Base aircrews’ capability to quickly and safely prepare an aircraft for a wartime mission. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

3) Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands: An Alliance Tripwire Tightens

The uninhabited Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea are administered by Japan and claimed by China. They matter because they sit under the U.S.–Japan defense treaty umbrella and because patrol patterns have grown denser and more assertive over the last decade. Compared with the South China Sea, the actors here are more professional—and the stakes are higher because of treaty obligations.

How It Starts. A seasonal peak in fishing and patrols brings three sets of ships into the same small box: Japanese coast guard vessels, Chinese law-enforcement cutters with militia “trawlers” nearby, and U.S. naval observers. A ramming incident between law-enforcement ships leaves one dead in the water; a minor collision becomes major when a fire breaks out. In the confusion, a Japanese helicopter receives a fire-control lock from a nearby radar; Tokyo interprets it as a threat and warns of counter-measures.

Why It Escalates. Tokyo cannot be seen to yield on administration; Beijing cannot be seen to legitimize “foreign occupation.” Washington must signal that the treaty covers attacks on Japanese ships performing administrative duties. All three governments face domestic pressure to stand firm, and all three believe the other two will blink first.

Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Dewey (DDG 105) transits the South China Sea. Dewey is part of the Sterett-Dewey Surface Action Group and is the third deploying group operating under the command and control construct called 3rd Fleet Forward. The U.S. 3rd Fleet operating forward offers additional options to the Pacific Fleet commander by leveraging the capabilities of 3rd and 7th Fleets. (U.S. Navy Photo By Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Kryzentia Weiermann/ Released)

The War Path. A Chinese missile destroyer that pushes too close is illuminated by a Japanese fire-control radar. In a tight turn, the boat’s commander fires a warning shot; the Japanese ship answers with a disabling burst; casualties result. The U.S. deploys an air-defense destroyer and combat air patrols. Mainland missiles move to high alert; Japanese and U.S. bases prepare for harassment fires. One more misstep and a treaty turns a local quarrel into a multi-actor conflict.

What Could Prevent It. A standing incident board with representatives from all three that convenes within hours at a neutral location; pre-agreed salvage and medical arrangements regardless of fault; and seasonal deconfliction boxes that all sides respect—with clear penalties that don’t require military force.

4) Unsafe Aerial Intercept: A New EP-3 Moment

In 2001, a Chinese fighter collided with a U.S. EP-3 reconnaissance plane over the South China Sea. The Chinese pilot died; the U.S. crew made an emergency landing and was detained before release. Replace that analog crisis with 2025 realities: more flights, faster timelines, live video, and social media that weaponizes outrage.

How It Starts. A slow, lumbering U.S. surveillance aircraft flies in international airspace near a sensitive Chinese exercise. A J-20 fighter conducts an unsafe close pass to signal displeasure, clips a winglet, and both aircraft are suddenly in distress. The fighter goes down; the U.S. crew broadcasts an emergency and diverts toward the nearest runway—on an island that Beijing controls or a base in a third country.

China J-20 Weapons. Image Credit: Chinese Weibo.

Why It Escalates. Every second is streamed. Narratives harden in real time: one side sees reckless provocation; the other sees dangerous harassment. Search-and-rescue assets scramble from both sides and converge. A rescue helicopter is warned off; a flare is misread; shots are fired over water.

The War Path. A rescue boat is disabled; a distressed crew member is seized “for questioning”; outraged statements box leaders in. Aircraft return armed “for self-protection.” The next intercept ends with a missile shot—justified as defense by the shooter, treated as aggression by the target. Within 24 hours, the focus shifts from the original mishap to protecting rescue and recovery forces, with both sides readying strikes on nearby airfields and radar sites.

What Could Prevent It. Professional intercept standards that both sides enforce; persistent joint training on air-to-air etiquette; pre-filed SAR playbooks that specify who goes where and what frequencies to use; and an understanding that emergency landings do not change sovereignty. Most of all, a hotline that works at the wing commander level—not just at the very top.

5) Naval Accident At Sea: Metal Meets Metal

Modern warships sometimes maneuver dangerously close—photographs prove it. Add autonomous systems, electronic warfare that can briefly confuse sensors, and crews who are human. Accidents happen.

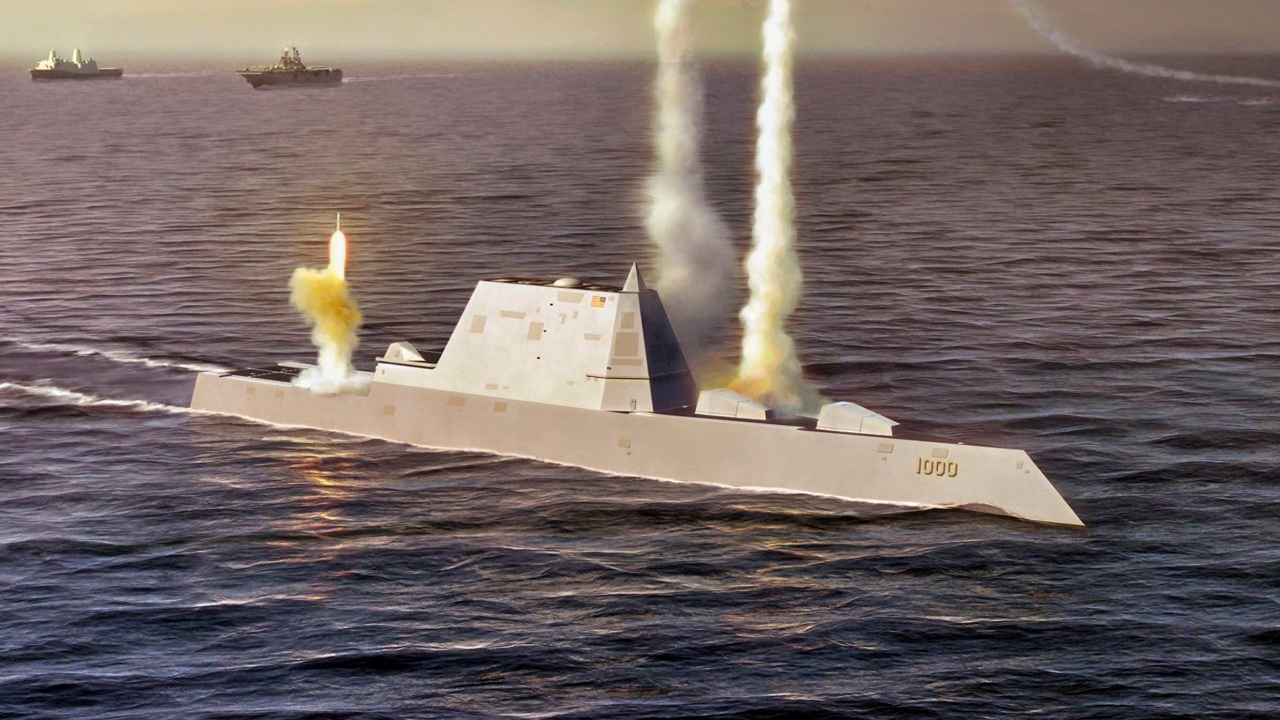

The US Navy’s troubled Zumwalt-class destroyers are being revitalized with the integration of Conventional Prompt Strike (CPS) hypersonic missiles, transforming them into powerful long-range strike platforms. The original class of 32 ships was cut to just three after its Advanced Gun System failed due to exorbitant costs. Now, these stealthy, $8 billion warships are having their defunct guns replaced with vertical launch tubes for hypersonic weapons. This upgrade will dramatically increase their strike range from a mere 63 miles to over 1,700 miles, making the Zumwalts relevant and formidable assets for deterring adversaries like China in the 21st century.

How It Starts. Two destroyers shadow each other across a chokepoint. Each tries to “shoulder” the other off an intended track without making contact. A momentary loss of steering or a misjudged swing brings metal-to-metal impact. In the scrape, a missile canister is damaged and cooks off; sailors are injured; a small fire threatens a magazine.

Why It Escalates. Both captains call for help; both nations push additional ships and aircraft to the scene; both declare exclusion zones. The nervous logic of self-defense kicks in—point defenses are armed, guns are manned, and helicopters fly low to spot for damage. Loose talk on open channels is recorded and rebroadcast within minutes.

The War Path. A damage-control team is mistaken for a boarding party; rounds are fired. The other ship responds with a short-range missile to end the perceived threat. A once-deniable scrape becomes a clear exchange of fire. Reinforcements arrive with standing orders to prevent further “aggression,” and an accidental collision has become the first battle of a war neither side planned.

What Could Prevent It. Credible INCSEA-style (Incidents at Sea) agreements that specify minimum distances, passing rules, and recovery protocols; body-camera-like data (cockpit/bridge video securely time-stamped) shared after incidents; and punishment for crews that violate professional standards, publicly enough to deter copycats.

USS John Finn (DDG 113) arrives Nov. 15 at the Port of Hueneme for routine Combat System Assessment Team (CSAT) repairs and training. The ship is one of four in the fleet with an Optical Dazzling Interdictor, Navy — also known as ODIN. The ODIN laser weapon system stuns enemy drones threatening surface ships. The destroyer also has two helicopter hangars, big enough to hold an MH-60R Seahawk Romeo multi-mission helicopter and the MH-60S Knighthawk Sierra helicopter. (U.S. Navy Photo by Dana Rene White/Released)

Why 2025 Is More Dangerous Than 2001

Three structural shifts make escalation faster and harder to control today:

Speed of Information. Everyone is a broadcaster; outrage is instantaneous. Leaders lose the luxury of ambiguity—what buys time in diplomacy can look like weakness to an online audience. Policies must assume minutes, not days, to frame an incident.

Kill Chains at Scale. Space, cyber, long-range missiles, and drones create compressed timelines. The temptation to blind the other side’s sensors “preemptively” is high, but blinding is indistinguishable from preparing to strike—an escalator in its own right.

Fragile Guardrails. Military-to-military dialogue mechanisms exist but are often dormant just when they’re needed, or too senior to move quickly. Without rehearsed protocols at the unit level, even perfect leader hotlines can ring too late.

(June 11, 2017) Sailors aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Pinckney (DDG 91) stand in formation as the ship pulls alongside the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN 68) to conduct a replenishment-at-sea. The Pinckney is currently underway as part of the Nimitz Carrier Strike Group on a regularly scheduled deployment to the Western Pacific and Indian Oceans. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Craig Z. Rodarte/Released)

The Four Rungs That Turn Incidents Into Wars

Across all five flashpoints, escalation tends to climb the same ladder:

Friction. Dangerous maneuver, close intercept, or legal challenge.

Damage. People hurt or hardware lost; domestic audiences harden.

Protection. Reinforcements rush in; exclusion zones and escorts appear; weapons go from safe to “up.”

Punishment. One side seeks to restore deterrence with a visible, limited strike—often against sensors or runways. The other answers in kind. Now both are killing enablers, and the logic of a broader campaign takes hold.

The policy task is to interrupt the climb—ideally before rung three.

How To Keep Sparks From Becoming Fires

Codify Behavior Where Contact Is Routine. Publish and practice air and maritime intercept standards; embed them in training, not just memos. Discipline at 500 feet prevents diplomacy at the 5th floor.

The Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Lassen (DDG 82) moves into position for an underway exercise with the British Royal Navy aircraft carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth (R08) and Pre-Commissioning Unit (PCU) Michael Monsoor (DDG 1001). The future USS Michael Monsoor is the second ship in the Zumwalt-class of guided-missile destroyers. (Photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class John Philip Wagner, Jr./Released)

Make Hotlines Tactical And Redundant. Wing commander to wing commander; destroyer CO to destroyer CO. Add language-qualified controllers and backup channels when jamming or outages hit.

Pre-Agree On Rescue. Search-and-rescue is where humanitarian instinct and national pride collide. Shared procedures and neutral observers save lives—and keep guns quiet while people are pulled from the water.

Use Mixed Presence Wisely. Third-party ships and aircraft (from neutral states or regional partners) can lower temperature by documenting behavior and offering face-saving off-ramps.

Practice De-Escalation As A Mission. Exercises should include stand-down drills and disengagement choreography, with rewards for crews who solve the scenario without escalating. Culture follows incentives.

Virginia-class attack submarine USS North Carolina (SSN 777) sails in formation, off the coast of Hawaii during Exercise Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2024, July 22. Twenty-nine nations, 40 surface ships, three submarines, 14 national land forces, more than 150 aircraft and 25,000 personnel are participating in RIMPAC in and around the Hawaiian Islands, June 27 to Aug. 1. The world’s largest international maritime exercise, RIMPAC provides a unique training opportunity while fostering and sustaining cooperative relationships among participants critical to ensuring the safety of sea lanes and security on the world’s oceans. RIMPAC 2024 is the 29th exercise in the series that began in 1971. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class John Bellino)

Clarify Red Lines—Quietly. Public vagueness can be useful; private clarity is vital. Each capital should know which acts will trigger what responses, and which will not. Ambiguity without back-channel clarity is a recipe for misreadings.

Why “Accidental” Doesn’t Mean “Unavoidable”

It is fashionable to say war is inevitable. It is not. The same proximity that breeds risk also creates routines and relationships that can be leveraged. Pilots who repeatedly see the same adversary crews build grudging respect; ship COs who talk directly can deconflict in plain language. The challenge is political: deterrence requires firmness; stability requires restraint. Both can coexist if leaders invest in the unglamorous mechanics of staying left of boom.

The Harsh Reality If Deterrence Fails

Should a war begin, it will not stay small for long. Both sides will strike enablers—satellites, radars, logistics hubs—because that is what modern doctrine demands. The region’s economies will shudder; sea lanes will narrow; allied capitals will be forced to choose. This is not an argument for yielding in crises; it is an argument for serious crisis management before crises. The cost of improvisation in the first 72 hours would be measured in lives, credibility, and years of recovery.

PERSIAN GULF (March 20, 2009) The Los Angeles-class attack submarine USS Hartford (SSN 768) is underway in the Persian Gulf after a collision with the amphibious transport dock ship USS New Orleans (LPD 18). Hartford sustained damage to her sail,

but the propulsion plant of the nuclear-powered submarine was unaffected by

this collision. (U.S. Navy photo/Released)

The Bottom Line

A U.S.–China war is more likely to start with bad luck and bad choices than with a formal decision. The five flashpoints outlined here—South China Sea coercion, a Taiwan blockade crisis, Senkaku confrontations, unsafe aerial intercepts, and naval accidents—share the same anatomy: dense operations, ambiguous rules, rapid politics, and compressed military timelines.

Preventing war is not softness; it is strategy. It means professional behavior where crews meet, private clarity where leaders decide, and practical protocols for the day a camera catches more than bravado. The way to win a war is to deter it. The way to deter it is to prepare for the incident, not just the battle.

About the Author: Harry J. Kazianis

Harry J. Kazianis (@Grecianformula) is Editor-In-Chief and President of National Security Journal. He was the former Senior Director of National Security Affairs at the Center for the National Interest (CFTNI), a foreign policy think tank founded by Richard Nixon based in Washington, DC. Harry has over a decade of experience in think tanks and national security publishing. His ideas have been published in the NY Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN, and many other outlets worldwide. He has held positions at CSIS, the Heritage Foundation, the University of Nottingham, and several other institutions related to national security research and studies. He is the former Executive Editor of the National Interest and the Diplomat. He holds a Master’s degree focusing on international affairs from Harvard University.

More Military

The Iowa-Class Battleships Will Never Make Another Comeback

F-15C/D: The Best Fighter Jet Ever?

The Air Force’s Big FB-22 Raptor Stealth Bomber Mistake Still Stings

The Navy’s F-117 Nighthawk Stealth Fighter Mistake Still Stings

Swamplaw Yankee

September 29, 2025 at 10:55 am

Wow. Hogwart fantasies live!

OK. Now, tell us how much cash the PRC CCP funnels to the Putin dictatorship quarterly. What’s a trillion rubles more or less to the Xi Cabal?

Then, when does the Xi Cabal cut off or green light the crazed orc Ruuxxkies on blowing up the 5 reactors that Putin is holding as his poker hand.

Is that, a hold on Xi’s throat for cash funding the equipping of a 2 million conscript army in 4-5 WEEKS to sight see through out Europe?

US versus the Terrorist Kremlin imperial empire: Yeah. The last time the Yankees fought was at Iowa Jima. And, that was after the FDR Cabal cowarded for 1939, 1940, 1941 and 1942 as 98% of Yankee men yellow belly pretended Stalin orcs did not cuddle closely to NAZI Hitler.

Xi’s intelligence brains seem to be playing high-stakes poker on a level that the brilliant MAGA POTUS Trumpkins elite can not even conceive. -30-

Jim

September 29, 2025 at 11:12 am

Just this weekend there were reports of Chinese military activity around Taiwan, both by sea & air incursions across the median line between Taiwan and the mainland. And talk of a duel-use “ferry” buildup with capacity for possible amphibious invasion.

Yet, there are also rumors of a charm offensive from Xi wanting Trump to publicly reaffirm and commit to the One China policy.

The suggestions and scenarios presented herein are reasonable in theater proactive protocols to avoid unintentional war.

Hopefully, these prudent steps are backed by high-level diplomacy to reduce the constant “belly bumping” which as described can lead to escalation with dizzying speed.

And an idea towards identifying each escalation rung on the ladder with an eye toward not climbing towards some point of no return, possibly one we where don’t exactly know the threshold, until we’ve already passed it.

John

September 30, 2025 at 6:09 am

What is the likelihood that China will respect or cooperate with ameliorating these risks? These intentional provocations seem to be a Chinese strategy.