Key Points and Summary – While the U.S. has reaffirmed its commitment to providing nuclear-powered submarines to Australia under AUKUS, a critical analysis questions whether America’s fragile industrial base can actually deliver.

-The U.S. Navy already struggles to produce the two Virginia-class submarines needed annually for its own fleet, managing only about one per year.

Norfolk, VA. (May 7, 2008)-The Virginia-class submarine USS North Carolina (SSN 777) pulls into Naval Station Norfolk’s Pier 3 following a brief underway period. North Carolina was commissioned in Wilmington, N.C. on May 3, 2008. (U.S. Navy Photo By Mass Communications Specialist 3rd Class Kelvin Edwards) (RELEASED)

Transferring three to five Virginia-class boats to Australia, as planned, without a massive surge in shipyard capacity and skilled labor, would create a dangerous shortfall for the U.S. Navy precisely when China is expanding its own fleet.

-AUKUS’s success hinges entirely on rebuilding America’s submarine industrial might.

Can the U.S. Actually Build Enough Submarines for AUKUS?

The United States has once again nailed its colors to the mast of AUKUS. Washington’s reaffirmation of its commitment to Pillar 1 of the trilateral pact—the provision of nuclear-powered attack submarines to Australia and the British-Australian co-development of a next-generation SSN platform—was a signal of intent as bold as it was welcome.

But past the pageantry and photo-ops comes a more complex question: can America deliver?

Can the United States build enough submarines for both its own Navy and its closest allies?

The solution will depend on steel production, labor force, and time requirements because the current industrial capacity does not support the planned output.

(July 25, 2006)- The Australian Submarine HMAS Rankin (Hull 6) and the Los Angeles Class attack submarine USS Key West (SSN-722) prepare to join a multinational formation with other ships that participated in the Rim of the Pacific exercise. To commemorate the last day of RIMPAC, participating country’s naval vessels fell into ranks for a photo exercise. RIMPAC includes ships and personnel from the United States, Australia, Canada, Chile, Japan, Peru, the Republic of Korea, and the United Kingdom. RIMPAC trains U.S. allied forces to be interoperable and ready for a wide range of potential combined operations and missions. Abraham Lincoln Carrier Strike Group are currently underway on a scheduled Western Pacific deployment. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communications Specialist Seaman James R. Evans (RELEASED)

A Grand Design Meets a Fragile Base

Under the current plan, the United States will transfer three Virginia-class submarines to Australia starting in 2032, with the option for two more if the production line can support it.

In parallel, American and British shipyards will help to design and then build the SSN-AUKUS, a new hybrid platform expected to start rolling off Adelaide shipyards in the 2040s.

The Pentagon conducted its latest Submarine Industrial Base assessment to validate this strategy.

Still, the review revealed the ongoing core problem, which began when the submarine fleet reached its maximum operational threshold while shipyard operations experienced delays and performance issues.

The core challenge of the AUKUS gamble stems from the fact that America maintains its most valuable undersea deterrent through its attack submarines, which offer both speed and stealth capabilities for strike operations and Pacific intelligence gathering. Every hull that goes to Australia is one less that is available for the U.S. fleet.

The alliance logic of AUKUS remains powerful. Washington provides Australia with SSNs to expand its military capabilities, creating a distributed defense system that makes Chinese naval operations more difficult and establishes an unbreakable bond between Australia and Western defense structures.

The risk emerges because industrial capabilities for submarine production fail to meet the delivery targets that have been promised.

040730-N-1234E-001

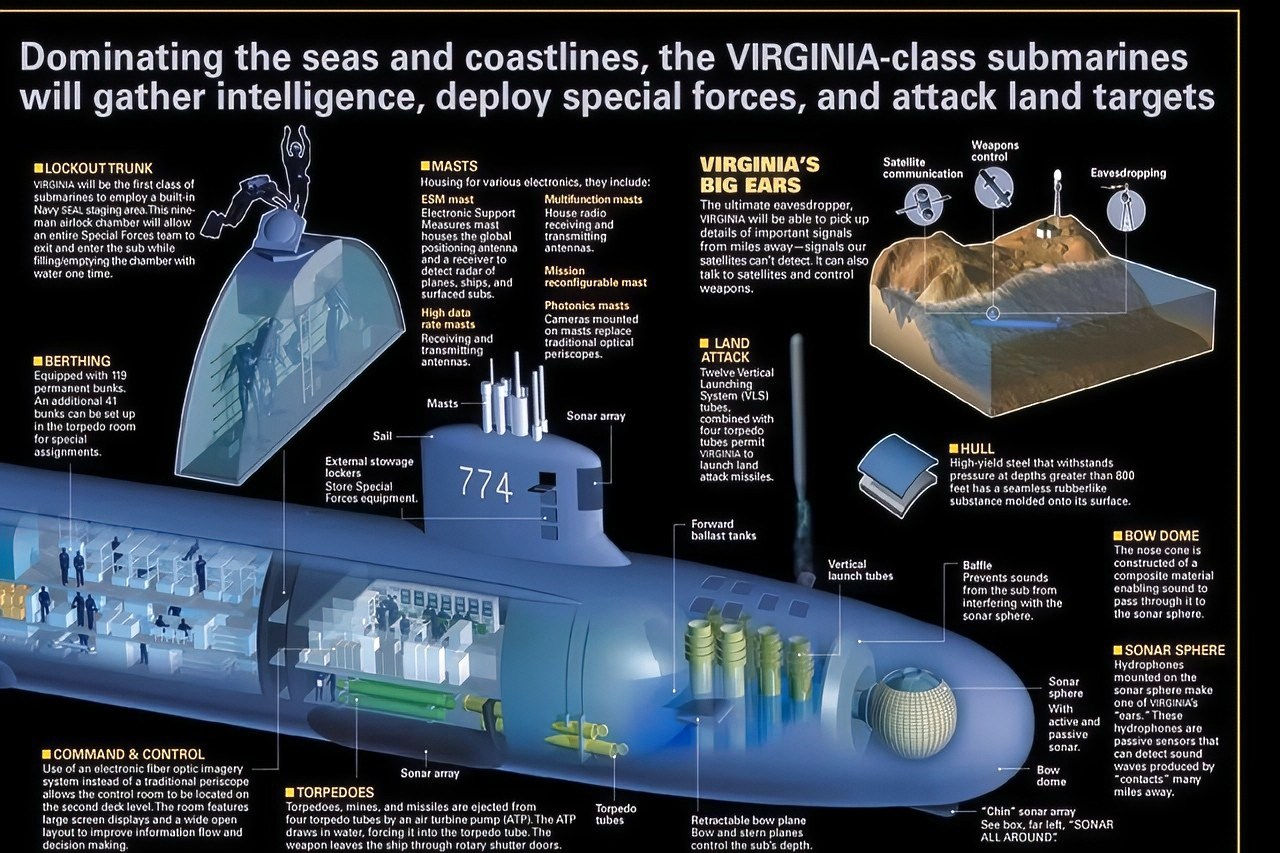

Groton, Conn. (July 30, 2004) – The nation’s newest and most advanced nuclear-powered attack submarine and the lead ship of its class, PCU Virginia (SSN 774) returns to the General Dynamics Electric Boat shipyard following the successful completion of its first voyage in open seas called “alpha” sea trials. Virginia is the Navy’s only major combatant ready to join the fleet that was designed with the post-Cold War security environment in mind and embodies the war fighting and operational capabilities required to dominate the littorals while maintaining undersea dominance in the open ocean. Virginia and the rest of the ships of its class are designed specifically to incorporate emergent technologies that will provide new capabilities to meet new threats. Virginia will be delivered to the U.S. Navy this fall. U.S. Navy photo by General Dynamics Electric Boat (RELEASED)

The Numbers Don’t Add Up

The Navy requires two Virginia-class boats annually to sustain its current fleet operations. It is getting about one. The two shipbuilding facilities at General Dynamics Electric Boat in Connecticut and Huntington Ingalls in Virginia are operating at full capacity to build new vessels while training their workforce and addressing ongoing supply chain issues that emerged during the pandemic.

The primary barrier to advancement stems from limitations in reactor component design. Skilled labor is in short supply. Key suppliers have left the market. The Navy needs to boost its output to reach double its current capacity before 2030 to meet U.S. needs and start exporting ships from any hull.

The current workforce faces an urgent problem. The construction of a nuclear submarine requires more than modular production methods because it represents a long-term endeavor that spans multiple generations.

Welders, engineers, and inspectors must complete several years of education and obtain the necessary certifications. The process of recovering lost expertise needs an extended period of time.

The AUKUS timeline indicates transfers occurring between 2030 and 2035, while Australian construction work is expected to begin in the 2040s.

The timeline depends on a future increase in skilled personnel and industrial capacity that has not yet occurred. Washington has started workforce-training partnerships and long-term supplier contracts to address the shortage, but these initiatives have not yet fully established themselves.

Then comes the arithmetic of strategic capacity. The U.S. attack-submarine inventory stands at just under fifty hulls—well below the Navy’s goal of sixty-six by the early 2040s. Aging Los Angeles-class boats are retiring faster than new Virginias can replace them.

The Columbia-class ballistic-missile submarine program, which rightly has top priority, is also absorbing much of the same yard space and skilled labor. That means delays anywhere ripple across both fleets.

Sending three to five Virginia-class submarines to Australia without a corresponding increase in production would leave the Navy with a significant shortfall, precisely as China accelerates its own undersea buildup.

Delivery Is the Measure of Power for AUKUS

Beijing already fields around seventy submarines, including an expanding number of nuclear-powered boats. Each new PLAN SSN erodes the margin of U.S. dominance. AUKUS aims to widen the allied flank, giving Australia the means to share the burden of maritime deterrence. But if the U.S. industrial base cannot sustain simultaneous commitments—to the Pacific, to AUKUS, and to its own fleet—the alliance could find itself undermining the very deterrence it seeks to strengthen.

China Nuclear Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

The way forward demands ruthless prioritization. First, Washington must execute a genuine surge plan for submarine production, not a paper exercise.

That means sustained, multi-year investment in yard expansion, workforce training, and supply-chain stabilization. One-off appropriations will not suffice; this must be treated as a strategic program on par with Cold War mobilization efforts. Second, the Navy needs to define precisely which submarines can be diverted to AUKUS, when, and under what conditions.

That clarity is essential both to preserve American deterrence and to give Canberra a realistic planning horizon. Third, communication among the AUKUS partners must be brutally honest. The alliance cannot be built on optimistic timelines or vague assurances.

The AUKUS recommitment is politically impressive but industrially precarious. It reflects the best instincts of U.S. strategy—arming allies to share the load and deter aggression.

Still, it also highlights the limitations of American manufacturing power in an era of constrained budgets and fragile supply lines.

The United States once built entire submarine classes in a fraction of the time it now takes to deliver a single boat. That era is gone, but the urgency that defined it must return.

In the end, the credibility of AUKUS will not be measured in communiqués or photo-ops but in tonnage. If the United States can rebuild its submarine industrial base—expanding capacity, securing materials, and cultivating the next generation of craftsmen—it will not only arm Australia but also reinforce its own maritime strength.

USS Missouri Virginia-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

If it fails, the gap will widen between promise and performance, and adversaries will notice. America’s recommitment to AUKUS is a statement of resolve. Its ability to deliver on that statement will determine whether this is a renaissance of allied power or an expensive exercise in wishful thinking. Words are cheap. Submarines are not.

Delivery—not declaration—will decide which kind of power the United States still is.

About the Author: Dr. Andrew Latham

Andrew Latham is a non-resident fellow at Defense Priorities and a professor of international relations and political theory at Macalester College in Saint Paul, MN. You can follow him on X: @aakatham. He writes a daily column for the National Security Journal.

More Military

Mach 6 SR-72 Darkstar Could Soon Be the ‘Fastest Plane on Earth’

America’s E-4B Doomsday Plane Has a Message for Russia and China

AIP: The Cheap Stealth Submarines the U.S. Navy Will Never Build

Russia’s Su-57 Felon Stealth Fighter Finally Opens Its ‘Secret’ Weapons Bay Doors

Canada’s Big F-35 Fighter Choice Is Stuck in ‘Stealth Limbo’